About Libre Knowledge

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

|

|

Libre knowledge (or free knowledge) is knowledge which may be acquired, interpreted and applied liberally. It can be re-formulated, adapted and extended according to one's needs, and shared with others for community benefit.

The adjective "libre" is used to indicate that the knowledge is in a state of "having freedom" or "liberty", irrespective of whether or not it is free of charge (avoiding the ambiguity in the word "free"). Nevertheless, the term "free knowledge" is also used in contexts where the specific meaning of free is clear.[1][2]

The term also refers to the cultural movement of libre knowledge (a sub-culture of the broader free culture movement[3]), inspired by the success of commons-based peer production in the development of libre software and Wikipedia, and guided by the principles of libre software,[4] and (for some) a conviction that knowledge should be accessible and shareable without restrictions.[5] Proponents tend to insist on the use of libre software, and libre file formats for most types of knowledge and cultural resources.

Use of the term libre knowledge arose early this century in the wake of discussions within the free software community considering the term "libre software" as an alternative to "free software" to avoid the ambiguity and associations (free/gratis suggests devoid of value to some), and thereby gain greater acceptance in the commercial world.[6][7] In the same way that libre software has become synonymous with free software as defined by the Free Software Foundation,[8] the terms "libre knowledge" and "free knowledge" synonymously associate equivalent freedoms with knowledge.[9]

While acknowledging the practical benefits of commons-based peer production as exemplified by prominent free/libre and open source software projects and Wikipedia, libre knowledge communities, or libre communities,[10] align themselves with the ethical perspective underpinning free/libre software.[10][11][12] Conversely, the related concept "open knowledge" acknowledges the ethical perspective,[13] but is framed in terms directly derived from open-source software which emphasises the pragmatic advantages of the open source production and development model.[9][14][15]

No distinction is made with cultural resources (or works), and published definitions of libre knowledge[9] and of libre cultural works[16] are essentially equivalent, being based on the same principles directly derived from the free software definition.

History and philosophy

Knowledge and communication

Knowledge sharing in the animal kingdom

The notion of knowledge which is shared freely, and that which is not, is evident in evolution - knowledge sharing within societies and communities, including ecological communities, is a natural part of survival, most notably among social animals[18] such as cetaceans[19] and primates. In some species (in addition to humans), information and learned behaviours communicated within a community and across generations has lead to distinct animal cultures.[17] Similarly, examples of knowledge not being shared, or misleading, is evident (for example) in studies of deception in animals.

Knowledge and language in human societies

In human communities, knowledge was originally transmitted across generations through direct experiential learning and orally in speech or song, and in various forms such as folklore, storytelling, sayings, ballads, songs, or chants.[20]

Early (upper Palaeolithic) human societies also communicated via parietal or rock art placed on boulder and cliff faces, cave walls and ceilings, and on the ground surface.[21]

Successively more expressive forms of representation (e.g. pictograms from about 9000 BC, ideograms, and other forms of proto-writing) developed, along with use of other media (e.g. papyrus[22] and paper) and writing tools (e.g. pens and printing presses)[23] which added portability and reproducibility, leading to the writing systems in use today.[24]

Writing

"Writing was such an important innovation because it freed the acquisition of knowledge from the limits of the human memory".[25] Apart from its utility in everyday life (e.g. keeping records[26] of transactions, births, deaths, inventories, etc.), writing enabled detailed knowledge to be shared across generations, and across geographical and cultural divides (through translation).

One of the arguments for sharing knowledge (and by implication, libre knowledge) is along the lines that writing (and now the Internet and other ICTs) have enabled the cumulative knowledge behind our greatest scientific and engineering achievements. This cumulatively shared knowledge is the foundation of our modern world. Isaac Newton wrote "If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants",[27] and indeed he was - those of Euclid, Descartes, "the great mathematicians and geometers not only of Newton's time and before Galileo but stretching all the way back to Euclid and the ancient Greeks".[25]

Liberty / Freedom

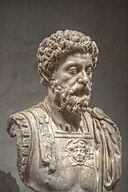

Philosophers from earliest times have considered the question of liberty. Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius (121–180 AD) wrote of equality in respect of the law, freedom of speech and freedom of the governed.[28]

Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), in Leviathan (1651, revised Latin edition 1668[29][30]) wrote of free will:

"a free man is he that in those things which by his strength and wit he is able to do is not hindered to do what he hath the will to do" (Leviathan, Part 2, Ch. XXI).

John Locke (1632–1704) distinguished free will in the sense of actions constrained only by the laws of nature not prohibited by law, and those constrained by "... the inconstant, uncertain, unknown, and arbitrary wills of others."[31]

The distinction was elaborated by John Stuart Mill (1806–1873), in his work, On Liberty,[32] and formalised as positive liberty and negative liberty by Isaiah Berlin in Two Concepts of Liberty.

Mill offered insight into the notions of soft tyranny and mutual liberty with his harm principle.[33]

"The only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others".[34]

An equivalent was earlier stated in France's Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789 as, "Liberty consists in the freedom to do everything which injures no one else; hence the exercise of the natural rights of each man has no limits except those which assure to the other members of the society the enjoyment of the same rights. These limits can only be determined by law."

Both types of freedom are pursued by libre knowledge, free culture, libre software, and related communities: positive liberty, enabling (and exercising) the freedom to cooperate in producing libre resources and in bringing about a better world; and negative liberty, protecting the community from tyranny and the arbitrary exercise of authority. For example, the libre software movement is behind copyleft and the GNU General Public License which enabled the community to cooperate in developing the GNU/Linux operating system and a wide variety of libre software. These licensing concepts and principles later inspired and informed the development of some of the Creative Commons licenses which in turn have helped the community grow the digital knowledge/cultural commons, and protect against abuse of the legal system or use of technologies such as DRM to exercise undue power over users/ authors/ artists/ etc.[35][36]

Libre knowledge

The long debated and discussed[37] concepts of knowledge and freedom, or liberty, have been brought together in the term "libre knowledge" at a time when our ability and need to communicate and share knowledge as a species is unprecedented. Proponents of libre knowledge share an ethic of sharing knowledge in order to bring about a better world.[38][39][40] Although many in the broader community focus on production of libre resources such as libre software, manuals and educational resources, some writers and organisations have attempted to provide or allude to the underlying philosophy, with reference to our understanding of the natural world (e.g. physics and evolution) and ethics.[41]

Inspiration and rationale for libre knowledge

Advocates of libre knowledge point to the role of knowledge and its sharing in bringing about the privileges enjoyed by modern society, and to the importance of sharing knowledge in bringing about equality, inclusivity, social justice and sustainability.[40]

The essence of the libre knowledge movement was expressed in 1954 in the title of Mark Van Doren's book "Man's right to knowledge and the free use thereof"[42] and Arthur Hays Sulzberger's paper of the same name.[43]

In the face of contemporary global issues (such as climate change and social inequalities), which require wide collaboration both in finding solutions and helping people on the ground with some urgency, libre knowledge is seen as an essential part of the process.[40] The opportunities are amplified by the rise of the Internet and associated information and communications technologies making it possible for large numbers of people to collaborate on large or complex projects,[44] and to serve the needs of individuals and of the planet.[40]

At the same time, some corporate and government entities seek to control the flow of knowledge for various reasons including profit (e.g. some sectors of the entertainment and ICT industries) and power (e.g. some governments),[36][45] creating a tension which has led to successive nuances or facets of the free culture movement[3][46] with different strategies and varying degrees of social conscience.

The core of the libre software movement for example, emphasises social solidarity and strongly aspires to purism by only using libre software and avoiding terminology which they believe detracts from their message of freedom.[4][47]

On the other hand, some sectors prefer to focus on production of libre resources with no qualms about using non-libre tools in the process. Examples include musicians using proprietary software to produce compositions which are later released under a libre licence, educators and students who are forced by their institutions to use specific proprietary software but release the learning resources they produce as libre learning resources.[48]

The vision of the Wikimedia Foundation (box right) and the success of Wikipedia, along with that of free/libre and open source software as a whole, are cited as shining examples of commons-based peer production and inspiration for libre knowledge.[49]

Libre and non-libre knowledge resources

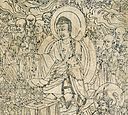

The concept of shareable knowledge resources is as old as print itself. The Diamond Sutra, the world's oldest dated printed book, includes the sentence:

Reverently [caused to be] made for universal free distribution by Wang Jie on behalf of his two parents on the 13th of the 4th moon of the 9th year of Xiantong [i.e. 11th May, AD 868][50]

Similarly, the concept of restricted knowledge is not new. Examples include some Religious texts[51] (e.g.closed canons[52]), esoteric and secret knowledge restricted to initiates such as those associated with mystery religions and martial arts. The reasons and means of restriction have varied over time according to political[53] and technical circumstances.

Copyright and libre knowledge

Much of the concern about the freedom of knowledge in modern times is linked to the development of copyright law which has generally become increasingly restrictive over time giving publishers more control over distribution and usage.[36] This trend is regarded by advocates of libre knowledge and free culture[54] as contrary to the original purpose of copyright, "to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts"[55] and out of step with the remix culture emerging with the Internet.[36]

Currently copyright is more often regarded as a tool to strengthen publishers' and authors' (and other types of producers') ability to control and profit from their works.

For some producers[56] of knowledge resources, deriving financial rewards is not their primary objective.[57] For example, in 1910 an English translation of Mahatma Gandhi's Hind Swaraj, recognised as the intellectual blueprint of India's freedom movement, was published with a copyright legend that read "No Rights Reserved".[58]

Liberation from (or a relaxation of)[59] restrictions on usage and sharing of knowledge resources and other works,[60] which are subject to copyright and other legal and technical limitations, is required for a free culture and for the potential of libre knowledge to be realised.[9] The Creative Commons licenses provide a convenient work-around for the default ("all rights reserved").[61]

Music

In addition to the oral traditions and written word, music has since pre-historic times been a channel for communicating knowledge and culture.[62] The concept of free or libre music (along with free culture) only became relevant with the rise of technologies which made it easy for anyone to record, remix, copy and share music easily - rendering the current state copyright law out of date.[63]

In 1994,[64] Ram Samudrala published the Free Music Philosophy. Mirroring the free software movement, it called for artists to allow their songs and compositions to be distributed with fewer copyright restrictions. The subsequent free music movement was reported on by diverse media outlets including Billboard,[65] Forbes,[66] Levi's Original Music Magazine,[67] The Free Radical,[68] Wired[69][70] and The New York Times,[71] and largely became a reality in the early 21st century.[72]

The term "libre music", or "free music" when 'free as in freedom' is clear from the context, refers to music or representations thereof released under libre licences which grant listeners and musicians the freedom to listen to, perform, mix (or otherwise use) the music, to copy, modify and share it in accordance with the applicable licence(s).

"Libre" has found its way into the naming of tools and projects concerned with enabling musicians (and listeners) to exercise these freedoms, and into the terminology used by some members of these communities.

Libre.fm, for example, is a music community web site which enables and encourages artists to share their music under libre licences; the site runs on libre software (GNU FM). The Mutopia Project is a volunteer-run effort to create a library of free content sheet music.

Libre Music Production (LMP) is a community-driven online resource whose goal is to "aid making music with libre software"; community knowledge about how to do this is shared under a libre licence (Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International).

Roots of "libre knowledge" in "libre software"

Since its inception in 1983, the free software community has been concerned with the rise of proprietary software and the threat it poses to its "hacker culture"[73] of cooperation and knowledge sharing.

Within the hacker culture, which emerged in academia in the 1960s, around the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)'s Tech Model Railroad Club (TMRC) [74] and the MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, a hacker ethic developed valuing access, freedom of information, and improvement to quality of life.[38]

Members of the free software community have always needed to engage in professional software development and provision of related services[75] without compromising these values. Some members regarded the ambiguity of the word "free" in the "free software" label as a hindrance when trying to engage with the commercial software community (free/gratis suggests devoid of value to some).

In the early to mid 1990s, alternatives were discussed within the free software community,[6] and the word "libre" emerged as a popular choice. Terms such as "libre software", "software libre" and FLOSS (Free/Libre and Open Source Software) subsequently gained some acceptance and have persisted. The terms software libre and FLOSS have been used by the European Commission[76][77] and "Libre" has become popular in the naming of libre software projects (e.g. LibreOffice, ProjectLibre, LibreSSL, ...) and events (e.g. Libre Planet).

The adjective "libre" has since been applied more broadly. For example, the term "libre knowledge" surfaced in the wake of these discussions early this century.[7]

In these contexts, the meaning of the word libre, and the concept of libre licensing, were clearly defined and understood well before the word was adopted. Libre knowledge inherits the philosophy of free software[4] and extends it into the realms of knowledge.[9]

Free Knowledge requires Free Software and Free File Formats (Jimmy Wales, 2004)[11]

The free culture movement

In reaction to the United States Congress passing the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act in 1998, academic and political activist Lawrence Lessig travelled the country giving hundreds of speeches at college campuses expounding the view that copyright is an obstacle to cultural production, knowledge sharing and technological innovation. In addition, Lessig published several books,[78] presented at various conferences and international events,[45][79] and founded the Creative Commons in 2001. These activities sparked the free culture movement and, with the release of the first set of Creative Commons copyright licences in December 2002, provided a foundation for its sustainability and impact.[80]

One of the more active manifestations of this movement, Students for Free Culture, advocate use of libre licences (i.e. licences which are compatible with the definition of free cultural works), and are active in discussions discouraging the use of non-libre licences such as Creative Commons licenses with restrictions on commercial use or on composing derived works.[81]

Open knowledge

In 1998, the term open source software was suggested as a substitute for free software because it avoided the ambiguity of ‘free’ in English, was not as value-laden as the term free software, and was therefore more acceptable to the commercial software industry.[82] In that year, David A. Wiley coined the term OpenContent to describe both a particular licence and the broader concept of non-software "open" works. Ironically, the OpenContent License is non-libre on account of restrictions on commercial use.[83]

You may not charge a fee for the OC itself. You may not charge a fee for the sole service of providing access to and/or use of the OC via a network (e.g. the Internet), whether it be via the World Wide Web, FTP, or any other method.

The "open" in terms such as open content, open education, OER and MOOC, has since come to describe a broader range of resources with varying degrees of openness. Openness can be assessed under the '5Rs Framework' based on the extent to which it can be retained, reused, revised, remixed and redistributed by members of the public without violating copyright law.[84] Unlike open source and free/libre content, there is no clear threshold that a work must reach to qualify as 'open content'.[85]

Open knowledge on the other hand has been formalised in a definition based on the open source software definition and is intended to encompass the same freedoms described in the free software and Free Cultural Works definitions.[86]

The open source movement and its off-shoots (e.g. open education and open knowledge) emphasise pragmatics such as the benefits of peer production, whereas the free software movement and aligned branches (e.g. elements of the free culture movement such as Students for Free Culture and proponents of libre knowledge) place greater value on ethics, freedom and social solidarity.[9][14][15]

Organizations and people

Whether their aim is to retain the Internet freedoms that have been its mainstay, or to create a better world, or to help members make a living using libre resources, some individuals and organisations have been significant in enabling and safeguarding a free culture conducive to libre knowledge in the digital age.

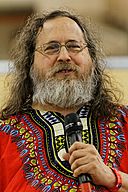

Richard Stallman, founder of the free software movement (1983) and currently President of the Free Software Foundation, has since the early 1980s been advocating for libre software, and campaigning against software patents, digital rights management, and other legal and technical systems which he sees as taking away users' freedoms. Stallman pioneered the concept of copyleft, which uses the principles of copyright law to preserve the right to use, modify and distribute libre software, and is the main author of the GNU General Public License (GPL), the most widely used libre software license.[87] This work established a libre software infrastructure for computing and the Internet and for the development of tools that make it possible for people to engage in the production and sharing of knowledge (and culture) in freedom.

Lawrence "Larry" Lessig, an American academic and political activist, is a supporter of free software and open spectrum[88] who advocates reduced legal restrictions on radio frequency spectrum, copyright, and trademark, particularly in technology applications, and has called for state-based activism to promote substantive reform of government with a Second Constitutional Convention.[89]

Lessig proposed the concept of "Free Culture"[90] and acknowledges Stallman's role in the free culture movement

[Stallman] changed the debate from is to ought. He made people see how much was at stake, and he built a device to carry these ideals forward ... It is not just about a certain kind of code, or enabling the Internet. [It's] much more about getting people to see the value in a certain kind of Internet. I don't think there is anyone else in that class, before or after.[91]

He is a former board member of the Free Software Foundation, Software Freedom Law Center and the Electronic Frontier Foundation[92] and has received awards for his legacy in the free culture movement including the Award for the Advancement of Free Software from the Free Software Foundation (FSF), and a Lifetime Achievement at the 2014 Webby Awards as cofounder of Creative Commons.[93]

Jimmy Wales is an American Internet entrepreneur best known as the co-founder and promoter of the online non-profit encyclopedia Wikipedia in 2001, with Larry Sanger and others. The success of Wikipedia and the vision he expressed for the Wikimedia Foundation fuelled and inspired the libre knowledge movement.

"Imagine a world in which every single human being can freely share in the sum of all knowledge. That's our commitment".

Other prominent people credited with being significant in the advance of the libre software / knowledge / culture movement include: Philippe Aigrain, David Bollier, Heather Ford, Eben Moglen, Benjamin Mako Hill, Larry Sanger, Tim Berners-Lee, Nikola Tesla,[94]

| Organisations | Notes |

|---|---|

| Hipatia | Vision: free knowledge, in action for towns and villages of the world[95] |

| Students for Free Culture | An international student organization working to promote free culture ideals, such as cultural participation and access to information. Students for Free Culture has over 30 chapters on college campuses around the world,[96] and a history of grassroots activism. |

| La Quadrature du Net | A French advocacy group that promotes digital rights and freedoms of citizens.[97] |

| Electronic Frontier Foundation | An international non-profit digital rights group based in the United States[98] |

| Free Knowledge Foundation | An organization aiming to promote Free Knowledge, including free software and free standards. It was founded in 2004 and is based in Madrid, Spain.[1] |

| Free Software Foundation | A 501(c)(3) non-profit organization founded by Richard Stallman on 4 October 1985 to support the free software movement, which promotes the universal freedom to study, distribute, create, and modify computer software,[99] with the organization's preference for software being distributed under copyleft ("share alike") terms,[100] such as with its own GNU General Public License.[101] |

| Creative Commons | A non-profit organization headquartered in Mountain View, California, United States, devoted to expanding the range of creative works available for others to build upon legally and to share.[102] The organization has released several copyright-licenses known as Creative Commons licenses free of charge to the public. These licenses allow creators to communicate which rights they reserve, and which rights they waive for the benefit of recipients or other creators.[103] |

| QuestionCopyright | A U.S.-based 501(c)(3) non-profit organization dedicated to expanding the range of acceptable public debate about copyright, and to reframing the way people—especially artists and those who work with them—think about copyright.[104] |

| Public Knowledge | A non-profit Washington, D.C.-based public interest group that is involved in intellectual property law, competition, and choice in the digital marketplace, and an open standards/end-to-end internet.[105] |

| League for Programming Freedom | LPF was founded in 1989 by Richard Stallman to unite free software developers as well as developers of proprietary software to fight against software patents and the extension of the scope of copyright. |

| Stanford Center for Internet and Society | A public interest technology law and policy program founded in 2000 by Lawrence Lessig at Stanford Law School and a part of Law, Science and Technology Program at Stanford Law School. CIS brings together scholars, academics, legislators, students, programmers, security researchers, and scientists to study the interaction of new technologies and the law and to examine how the synergy between the two can either promote or harm public goods like free speech, innovation, privacy, public commons, diversity, and scientific inquiry.[106] |

| Free Knowledge Institute | A not-for-profit organization founded in 2006 in The Netherlands. Inspired by the Free Software movement, the FKI fosters the free exchange of knowledge in all areas of society by promoting freedom of use, modification, copying and distribution of knowledge in four different but highly related fields: education, technology, culture and science. |

Libre manifestos and declarations

While valuing both but with a tendency to emphasise ethics and social solidarity over the pragmatics highlighted by open source, libre communities have from time to time released manifestos declaring their views, motives and intentions. Examples include the GNU Manifesto,[107][108] the Mozilla Manifesto, the Debian Social Contract and guidelines, and others from the libre software community, The Libre Society Manifesto / Libre Culture Manifesto, Hipatia's First and Second Manifestos, the Libre Communities Manifesto[109] and Declaration[10] relating to libre knowledge.

Underpinning these declarations is a rejection of the dominant model encoded in the legal system which treats digital works as if they were ownable physical objects. All express concern about the power of organisations and authorities to restrict access to and control the use of non-rivalrous digital cultural and knowledge resources through the prevailing legal system. They expound the value of universal access, freedom and sharing in bringing about a better world by empowering people to participate. Where intentions and actions are stated, these generally involve educating society on the value of this type of freedom and developing libre resources and tools for editing and sharing them.

Definitions

Libre definition

The adopted meaning of "libre", as it is currently used, was first formalised in the free software definition published by the Free Software Foundation in 1986.

Although limited to software, the four core freedoms defined therein formed the basis for various definitions emanating from the free culture movement. These include definitions of libre knowledge[110][111] and free cultural works.[112]

| Freedom # | Free Software definition | Libre Knowledge definition | Free Cultural Works definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | The freedom to run the program as you wish, for any purpose. | The freedom to use the work for any purpose. | The freedom to use the work and enjoy the benefits of using it. |

| 1 | The freedom to study how the program works, and change it so it does your computing as you wish. Access to the source code is a precondition for this. | The freedom to study its mechanisms, to be able to modify and adapt it to their own needs. | The freedom to study the work and to apply knowledge acquired from it. |

| 2 | The freedom to redistribute copies so you can help your neighbor. | The freedom to make and distribute copies, in whole or in part. | The freedom to make and redistribute copies, in whole or in part, of the information or expression. |

| 3 | The freedom to distribute copies of your modified versions to others. By doing this you can give the whole community a chance to benefit from your changes. Access to the source code is a precondition for this.

A program is free software if users have all of these freedoms. |

The freedom to enhance and/or extend the work and share the result. Freedoms 1 and 3 require free file formats and free software as defined by the Free Software Foundation. A knowledge or learning resource is free if users have all of these freedoms. |

The freedom to make changes and improvements, and to distribute derivative works.

In order to be recognized as "free" under this definition, a license must grant [these] freedoms without limitation. |

The definition of libre knowledge which appears at the very beginning of this article,[113] applies to knowledge in general, including tacit knowledge. Tacit knowledge, includes (for example) common knowledge which is shared freely within a community), and knowledge in a person's head which is difficult to transfer such as the ability to recognise faces.[114] These are regarded as implicitly libre in the sense that one is free to use and share that knowledge. The more formal part of the definition in the table above is most applicable to explicit knowledge, or digital knowledge resources, which are easily copied, modified and shared.[10]

(Explicit) knowledge is taken to include data, information, software and other resources used to represent and communicate knowledge.

Implicit in these definitions is the requirement that the resource is not restricted via technical means (e.g. DRM) or legal limitations (e.g. via copyright, trademarks or patents) which would prevent the user from being able to exercise these freedoms.[115][116]

Libre resources

Libre resources[113][117] (or libre works) are (typically digital) resources represented on a device or medium such as files in an open/free format containing text, an image, sound, software, source code, document, multimedia, etc. or combinations of these which have the same freedoms:

Libre implies freedom to access, read, listen to, watch, or otherwise experience the resource; to learn with, copy, perform, adapt and use it for any purpose; and to contribute and share enhancements or derived works.[109]

The definitions of libre resources[109] and libre knowledge were developed and refined[111] in the context of open education[118] where its proponents advocated alternative terms to OER such as LLR (Libre Learning Resources) and FORE (Free and Open Resources for Education)[119] emphasising the ethical principles of freedom, equality and sharing over the pragmatics associated with the word "open" (open source).

The primary concern during the development of these definitions was addressing the need to make learning resources accessible to people in the developing world. The resources would inevitably need to be adapted for local use, ideally by the recipients. To do so they would need the freedom to translate and recontextualise the resources and to distribute derived works on various media without restriction. The intent was to encourage people concerned with open education to distinguish "libre learning" which does not include restrictions on use or distribution. Proponents discouraged the use of licenses with restrictions on (e.g. commercial) usage, promoted copyleft as a means of growing the libre commons, and advocated libre licensing to enable a "copy-modify, mix and share" (free/libre or "read-write") culture and society.[9]

Although the definition of "libre resources" was originally developed within the libre knowledge community as "libre knowledge resources" (as an alternative to OER),[119] it was quickly generalised to "libre resources" and is now used to describe any digital resources available with the core freedoms (whether they carry the label "libre" or not). For example, open educational resources, open designs and open content which are released under libre licences are classed as libre resources.

Libre resources can also refer to hardware or firmware whose design is free of restrictions on usage, modification and sharing. The term "libreware" is also used in this way, though initially it was proposed as an alternative term for "free software".[120]

Libre knowledge resources

Explicit libre knowledge encompasses its components such as data, content, information, software and other resources used to represent and communicate knowledge.

Libre content

Free content, libre content, or free information, is any kind of non-software and non-data work, such as artwork, or other creative content that meets the free cultural works definition.[121] Free documentation is a term used by the Free Software Foundation to describe libre content that supports software such as user manuals.[122] Open content has also been used to describe these works, but it has come to be used to describe works with any added permissions over the copyright status quo.

Libre content[123] avoids this ambiguity. The four freedoms that must be guaranteed by free content are adapted from the four freedoms Richard Stallman called for in software.

Open data

Open data describes data which is freely available to everyone to use and republish without violating copyright law or sui generis database rights.

"Libre data" per se has not been formally defined. Its meaning is implied in the libre knowledge definition as data which may be copied, modified and shared in the same way as libre software or other libre resources.

Free, libre and open-source software (FLOSS)

The acronym FLOSS (free/libre and open-source software) was coined in 2001 by Rishab Aiyer Ghosh to refer to both the "open source software" and "free/libre software" camps, in order to avoid debate around these two terms.[14]

The Free Software Foundation accepts use of "FLOSS" for its intended purpose (neutrality), but does not use the acronyms FLOSS or FOSS, and advocates using the term "free software" or "libre software" to make a stand for freedom.[8]

Free/libre file formats

A free or libre file format is a published specification for storing digital data not encumbered by any copyright, trademark, patent or other restrictions.[124][125][126]

Free/libre protocols and open standards

Libre protocols are communications protocols without legal or technical restrictions. Open standards are less strictly defined, but by some definitions the term describes technical standards without legal restrictions.[126]

Free/libre network services

Although there is no formal universally agreed upon definition, free/libre network services are generally understood to refer to web services available with the same freedoms of libre software extended to this type of resource. For a web or network service to qualify as libre, the underlying data, formats, protocols, software and information resources generated and shared would all have to be libre. In addition, certain other criteria would need to be met beyond the core freedoms such as user privacy and net neutrality.[127][128]

Open source hardware and design

Open source hardware is hardware whose design is made publicly available so that anyone can study, modify, distribute, make, and sell the design or hardware based on that design.[130]

In terms of licensing, some open-source hardware projects simply use existing free and open-source software licenses,[131] or one of several new open hardware licenses designed to address issues specific to hardware designs.[132]

Despite superficial similarities to software licenses, most hardware licenses are fundamentally different: by nature, they typically rely more heavily on exceptions to patent law than on copyright law. Whereas a copyright license may control the distribution of the source code or design documents, a patent license may control the use and manufacturing of the physical device built from the design documents. This distinction is explicitly mentioned in the preamble of the TAPR Open Hardware License:

"... those who benefit from an OHL design may not bring lawsuits claiming that design infringes their patents or other intellectual property.".TAPR Open Hardware License in [133]

The Defensive Patent License (DPL), released in November 2014 in Berkeley, California[134] is aimed at protecting "innovators by networking patents into powerful, mutually-beneficial legal shields that are 100% committed to defending innovation".[135]

The term or label "libre hardware" is used with the implication of applying the same freedoms associated with libre software to hardware.[136] Proponents advocate using hardware that respects one's freedom (e.g. computers running fully-free distributions of the GNU/Linux operating system).[137]

On-going issues and challenges

The libre knowledge movement was largely inspired by the Libre software movement inheriting its philosophy and some of its practices. By definition, libre knowledge must be accessible and editable with libre software.[10][11][12] For this reason, libre communities also inherit the challenges faced by the libre software community.[9] Beyond the software, libre communities are also active in policy debates concerning freedom and the technology used to access, produce and share knowledge (e.g. privacy, surveillance, Software as a Service,[138] DRM and net neutrality), and concerning freedom issues arising in certain knowledge domains (e.g. synthetic biology).

Libre software

|

Impediments and challenges Digital rights management | Tivoization | Software patents and free software | Trusted Computing | Proprietary software | SCO-Linux controversies | Binary blobs Adoption issues OpenDocument format | Vendor lock-in | Open standards | Linux adoption About licences Free software licences | Copyleft | List of FSF-approved software licenses | List of OSI-approved software licences Common licences GNU General Public License | GNU Lesser General Public License | Modified BSD License | Mozilla Public License | MIT license | Apache License | Permissive free software licences Naming issues GNU/Linux naming controversy | Alternative terms for free software | Naming conflict between Debian and Mozilla

|

| (Challenges) |

Some libre communities, most notably in the libre software community such as the Free Software Foundation, take a strong stance against use of nonfree or non-libre or proprietary software - terms they use to refer to software which "doesn't respect users' freedom and community".[139] They claim that proprietary software is often malware[139] or includes antifeatures[140][141] or crippleware. These communities advocate exclusive use of libre software and support of libre file formats.[9][11] Those that do, face the same challenges, some of which are listed in the box on the right.

From the libre knowledge perspective, some of these issues generalise to knowledge. For example, the issue of patents[142] arises in some knowledge domains such as hardware, design, and synthetic biology; licensing issues generalise beyond software and manuals to other types of works such as art, music and educational resources; vendor lock-in can be imposed on students whose institutions are locked-in and require students to use proprietary software and non-libre file formats.[48]

Net neutrality

Net neutrality (also network neutrality, Internet neutrality or net equality) is the principle that Internet service providers and governments should treat all data on the Internet equally, not discriminating or charging differentially by user, content, site, platform, application, type of attached equipment, or mode of communication.

Neutrality proponents claim that telecom companies seek to impose a tiered service model in order to control the pipeline and thereby remove competition, create artificial scarcity, and oblige subscribers to buy their otherwise uncompetitive services.[143] Many believe net neutrality to be primarily important as a preservation of current freedoms.[144]

Advocates for free culture and libre knowledge, in relation to net neutrality, attribute much of the success of the Internet and the innovation it enabled[145] before the advent of such net biases to its inherent [146] (net) neutrality,[143][144] and stress the importance of Internet access for "learning and for the practical and meaningful exercise of freedom of expression and communication".[147]

Opposing Digital rights management

In 2006 the Free Software Foundation launched the Defective by Design campaign, an anti-DRM (digital rights management) initiative. DRM technology, dubbed "digital restrictions management" or "digital restrictions mechanisms" by opponents,[148][149][150][151][152] restricts users’ ability to freely use their purchased movies, music, literature, software, and hardware in ways they are accustomed to with ordinary non-restricted media (such as books and audio compact discs).

The philosophy of the initiative is that DRM is designed to be deliberately defective, to restrict the use of the product. This, they claim, cripples the future of digital freedom. The group aims to target "Big Media, unhelpful manufacturers, and DRM distributors" and to bring public awareness of the issue and increase participation in the initiative. It represents one of the first efforts of the Free Software Foundation to find common cause with mainstream social activists, and to encourage libre software advocates to become socially involved.

Synthetic biology

National and international policies and approaches to managing the flow of knowledge in this relatively new field are still under debate,[153] as are the bioethics and security issues.[154] The issues are not seen as new because they were raised during the earlier recombinant DNA and genetically-modified organism (GMO) debates and there were already extensive regulations of genetic engineering and pathogen research in place in the U.S.A., Europe and the rest of the world.[155]

On account of similarities between genetic code and software, some have proposed (or explored) applying principles developed in the libre software community in this field.[156][157] Also, in common with the hacker culture characteristic of the libre software community, a culture of biohacking has emerged[158] with a similar ethic.[159][160][161][162][163]

Biohacking emerged in a growing trend of non-institutional science and technology development.[159][164][165] As in the software industry, there is a tension between those who believe in "biofreedom" and the corporates who seek to own and commoditise both the data and tools for analysing biological data.[166] Components (e.g. BioBricks) are designed and developed to create "biological machines" which may be "parts", "devices" or "systems". In this sense, the results of synthetic biology are analogous to hardware and designs which are generally protected primarily via patents.

As an example, the Biological Innovation for Open Society (BIOS) project implemented a patentleft system to encourage re-contribution and collaborative innovation of their technology. BIOS holds a patented technology for transferring genes in plants, and licenses the technology under the terms that, if a license holder improves the gene transfer tool and patents the improvement, then their improvement must be made available to all the other license holders.[167]

On the other hand, DNA sequences share characteristics of both data (see Open data above - sui generis data protection laws may apply) and software.[168] In some jurisdictions software is not patentable and copyright is used as the main means of rights protection. The patentability of the products of synthetic biology are still in question.[153][169]

Whatever policy outcomes emerge from these discussions and initiatives, the resources involved (tools and outputs of synthetic biology) are considered libre if the four core freedoms apply and they are not encumbered by patents or other legal or technical restrictions.

Related concepts

Libre community

A libre community is a community of people who engage in commons-based peer production, dissemination and/or advocacy of libre knowledge or other libre resources.[109]

Members typically use libre software and tend to use terminology[47] aligned with the philosophy of the libre software movement.[4] Some libre communities regard themselves as hackers[73] and retain the hacker ethic which emerged from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)'s Tech Model Railroad Club (TMRC)[74] and MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory in the 1950s and 1960s. However, the term has come to refer to any group of people working on libre resources (i.e. resources released under a libre licence).

Liberated resources

| Java |

|---|

| e.g. The Java programming language was liberated between November 2006 and May 2007.[170][171] |

Liberated software is software formerly published under a proprietary license but later released with the source code and a more liberal license. While such software typically becomes libre software, open source software or public domain, this is not always the case and some restrictions may apply. In some cases, the company continues to publish proprietary releases alongside the non-proprietary version.

Similarly, "liberated knowledge" or "liberated cultural resources", etc. refer to proprietary resources previously not universally available, or restricted in use via price or legal barriers, which have since been re-released without those restrictions. The restrictions are usually lifted via copyright. For example, the copyright expires, or the copyright holder re-releases the resource under a Creative Commons licence. However, for some resources, lifting of patent restrictions may also be required. Mechanisms for protection against patent restrictions include promises from patent holders (which are often received with some skepticism), patent pools and use of licences which address patents such as the Defensive Patent License.

For software, IBM, Novell, Philips, Red Hat, and Sony founded the Open Invention Network (OIN) in 2005. OIN is a company that acquires patents and offers them royalty free "to any company, institution or individual that agrees not to assert its patents against the Linux operating system or certain Linux-related applications".[172]

It should be noted that while acknowledging that patents may be appropriate in some industries, many of the libre persuasion question their validity in fields such as software, their utility in encouraging innovation, and actively oppose the patent system where appropriate.[142]

Open educational resources

There are competing definitions of open educational resources, but they describe at least resources that are accessible for no charge to students and educators, and typically under a public copyright licence that permits the resource to be shared and adapted.

As with open access, narrower definitions of open educational resources do exist. The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation definition describes open educational resources as either "resid[ing] in the public domain or [...] released under an intellectual property license that permits their free use or re-purposing by others."[173] Under this definition, all open educational resources would qualify as libre.

In practice, however, many open educational resources—even those under public copyright licences—are non-libre. For example, MIT OpenCourseWare and most of the learning resources on Coursera and other MOOCs, are under the non-libre Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike licence.

Open access

In 2008, Peter Suber and Stevan Harnad, members of the open access community, proposed the use of the terms 'gratis open access' and 'libre open access' to resolve confusion within the open access community between resources that were open because they were free of price restrictions and those that were open because they were free of price and some permission restrictions.[175]

Significantly, this definition of libre open access covered works for which any amount of permissions restrictions had been lifted. This definition breaks from the established use of the term libre to refer to free/libre content and free/libre software, where a specific threshold of permission must be reached.

The definition of open access reached in the Budapest, Bethesda and Berlin statements (referred to collectively as the 'BBB Definition')[176] specifies the permission barriers that must be lowered for a work to be considered open access:

By "open access" to this literature, we mean its free availability on the public internet, permitting any users to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of these articles, crawl them for indexing, pass them as data to software, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without financial, legal, or technical barriers other than those inseparable from gaining access to the internet itself. The only constraint on reproduction and distribution, and the only role for copyright in this domain, should be to give authors control over the integrity of their work and the right to be properly acknowledged and cited. (Budapest Open Access Initiative statement)[176]

A work is open access where the copyright holder has given general permission to copy, use, distribute, transmit and display the work publicly and to make and distribute derivative works, in any digital medium for any responsible purpose, subject to proper attribution of authorship. (Bethesda and Berlin statements)[176]

All open access works that meet the BBB definition would qualify as libre. However, in the years following the BBB statements, some writers used the term "open access" in the BBB sense while others used it for works that were merely gratis or free of price restrictions. When Harnad wanted to write about all-rights-reserved gratis articles, he was faced with the option of referring to them as "open access" (in contravention of the BBB definitions) or redefining "open access" to include non-libre works.

The compromise arrived at by Suber and Harnad was to identify two classes of open access: gratis open access, which is merely free of charge, and libre open access, which is free of charge as well as free from one or more permission restrictions. However, the standard definition of libre requires that a work be free from a particular set of permission restrictions; some works that qualify as libre open access would not qualify as libre (for example, those with a Creative Commons NonCommercial or NoDerivatives licence term).

Suber continues to support the use of the Creative Commons Attribution licence for articles, a libre licence in every sense of the word.[177]

Creative Commons

See Libre knowledge and Creative Commons (on Wikipedia).

See also

- Knowledge

- Common knowledge

- Knowledge commons

- Freedom (philosophy)

- Freedom (political)

- Jimbo Wales' declaration of how Wikipedia is a free encyclopedia

- Libre software

- Free software movement

- History of free and open-source software

- Free Culture movement

- the book

- Definition of Free Cultural Works

- Libre content

- Creative Commons

- Freedom of information

- Freedom of information laws by country

- List of libre licenses

- Libre Society

- Access to knowledge movement

- Access2Research

- Academic Spring

- Openness (and its See also section)

- Information wants to be free

- Edupunk

- Biological patent

Further reading

- 1909: Mahatma Gandhi: One of Gandhi's earliest publications, Hind Swaraj published in Gujarati in 1909 is recognized as the intellectual blueprint of India's freedom movement. The book was translated into English the next year, with a copyright legend that read "No Rights Reserved".[58]

- 1945: The Use of Knowledge in Society - F. A. Hayek.[178] Jimmy Wales (co-founder of Wikipedia) cites this book, which he read as an undergraduate,[179] as "central" to his thinking about "how to manage the Wikipedia project".[180] Hayek argued that information is decentralized - that each individual only knows a small fraction of what is known collectively - and that as a result, decisions are best made by those with local knowledge rather than by a central authority.[180]

- 1954: Mark Van Doren (book): "Man's right to knowledge and the free use thereof".[42]

- 1954: Arthur Hays Sulzberger, Man's right to knowledge and the free use thereof, University of Hawaii, Occasional Paper 61, Honolulu.[43]

- 1974: Computer Lib/Dream Machines (1974) by Ted Nelson describes some tenets of the hacker ethic.

- 1984: Steven Levy, Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution, Doubleday, USA. Dell, 1994, with a new afterword. Penguin Books, New York, 2001.

- 2001: Pekka Himanen, The Hacker Ethic and the Spirit of the Information Age with a prologue by Manuel Castelles, an epilogue by Linus Torvalds and an appendix on the history of hackerism.

- 2001: Fle3 announcement - "Fle3 - libre software for (libre) knowledge building"[7] - an example of use of the term (libre) knowledge generalising from libre software to libre knowledge.

- 2002 (at the latest): The first Hipatia manifesto was published in Spanish. The current English version and a second manifesto are available on the Hipatia web site.

- 2002: The Budapest Open Access Initiative called for "open access" to research in all fields.

- 2002: Free Software, Free Society: Selected Essays of Richard M. Stallman.[181] - a collection of essays by Richard Stallman which explains the philosophy of libre software, the foundation of the philosophy of libre knowledge and libre culture.

- 2000-2004: Lawrence Lessig has published several books, ultimately motivating the free culture movement, which provide background and discuss the tension between a desired free, read/write Internet culture versus the permission culture of control via legal and technical means. These include Free Culture,[54] Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace,[182] Code: Version 2.0[183] and The Future of Ideas.[184]

- 2004: Quo vadis, libre software?, Jesús M. González-Barahona, v0.8.1, September. Archived on 25 December 2012.

- 2004: Jimmy Wales's blog posting: "Free Knowledge requires Free Software and Free File Formats". This blog posting provides a rationale for the libre knowledge movement to use libre file formats.

- 2004: Yochai Benkler published "Coase's Penguin" introducing Commons-based peer production a new mode of production for the 21st Century.[185]

- 2005: Benjamin Mako Hill. "Towards a standard of freedom: Creative Commons and the free software movement".

- 2006: David M. Berry and Giles Moss. The politics of the libre commons, First Monday, volume 11, number 9 (September 2006).

- 2006: Yochai Benkler published The Wealth of Networks[186] which expands on the concept of commons-based peer production and implications.

- 2007: Charlotte Hess and Elinor Ostrom edited a book called "Understanding Knowledge as a Commons: from theory to practice" which reflects current interest in this phenomenon and some of the history of the knowledge commons.[187]

- 2007: Kim Tucker released the Say "Libre" essay encouraging people in the "open" community to use the adjective libre to disambiguate free and instead of "open" where applicable (i.e. when describing resources released under licences which grant the four core freedoms).[9]

- 2008: Berry, D. M & Moss, G. (2008). Libre Culture: Meditations on Free Culture. Canada: Pygmalion Books.[188]

- 2009: FCF developed the Charter for Innovation, Creativity and Access to Knowledge. A Libre Interpretation was also prepared which also orientates towards sustainability as a goal. A version of the latter using the word "free" rather than "libre" is available on the Free Knowledge Institute wiki.

- 2011: Chris Sakkas, Share This Book: a quick introduction to libre.

- 2012: Richard Stallman, Free/Libre Scientific Publishing.

Notes and references

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Free Knowledge Foundation (libre.org).

- ↑ The Free Knowledge Institute (FKI) (Founding Principles).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 The broader free culture movement includes other sub-communities which do not fully embrace the principles associated with libre knowledge. For example, some do not aspire to use exclusively libre software, and some release work under non-libre Creative Commons licences.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 The philosophy of libre software is expressed in the Philosophy of the GNU Project articles.

- ↑ See for example Missionary Church of Kopimism and the Hipatia manifestos (first and second).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Quo vadis, libre software?, Jesús M. González-Barahona, v0.8.1, work in progress, September 2004. Archived on 25 December 2012.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Leinonen, Teemu. 20 Nov 2001. Fle3 - libre software for (libre) knowledge building, accessed on 27 September 2007.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 FLOSS and FOSS by Richard Stallman.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 9.9 Tucker K., 2007. Say "Libre", also previously published on libre.org.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Declaration on libre knowledge also (archived) on the Libre Communities web site.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Free Knowledge requires Free Software and Free File Formats (Jimmy Wales, 2004)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Another example which reflects this angle is Hipatia - Free knowledge in action for the people of the world.

- ↑ The essential meaning of the Open Definition is intended to match "free" or "libre" in definitions derived from the free software definition.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Why Open Source misses the point of Free Software by Richard Stallman.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Elliott, M. S.; Scacchi, Walt (2008). "Mobilization of software developers: The free software movement". Information Technology & People 21 (1): 4. .

- ↑ Free Cultural Works and equivalent Libre Cultural Works Definition.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Several examples are given in the Animal culture article on Wikipedia.

- ↑ See for example Tool use by animals in which most behaviours are learned (not innate).

- ↑

An example is shared by Matt Kaplan in Unique orca hunting technique documented: A pack of killer whales uses waves to knock seals off the ice (Published online on 14 December 2007, Nature, doi:10.1038/news.2007.380) referring to Visser, I. N. et al. Antarctic peninsula killer whales (Orcinus orca) hunt seals and a penguin on floating ice

(pdf), Marine Mammal Science, doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2007.00163.x (2007), (downloadable from Orca Research). Visser et al. "speculate that such complex coordinated hunting behaviors are culturally transmitted".

There are other examples of hunting techniques where adults appear to be teaching their offspring. See for example, Understanding Orca Culture: Researchers have found a variety of complex, learned behaviors that differ from pod to pod, Lisa Stiffler, Smithsonian Magazine, August 2011: "Scientists have found increasing evidence that culture shapes what and how orcas eat, what they do for fun, even their choice of mates. (Michael Parfit / Mountainside Films)" (retrieved on 9 Feb. 2015). - ↑ See Oral tradition and, for example, oral history, oral literature, oral law and other knowledges.

- ↑ Whitley, David S. (2005). Introduction to Rock Art Research. Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press. .

- ↑ Other ancient writing materials include Palm leaf manuscript (India), Amate (Mesoamerica), Ostracon, Wax tablets, Clay tablets, Birch bark documents and Parchment.

- ↑ Additional examples of writing tools include cylinder seals, Woodblock printing, pens, printing presses, etc..

- ↑ See History of writing for more background.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Cox, B. 2014. Narrating "Human Universe", BBC Documentary.

- ↑ Inventions_of_writing: Writing numbers for the purpose of record keeping began long before the writing of language. See History of writing ancient numbers for how the writing of numbers began.

- ↑ In a letter to his rival Robert Hooke dated February 5, 1676 [O.S.]; see "The correspondence of Isaac Newton, volume 1", edited by HW Turnbull, 1959, p. 416 (February 15, 1676 [N.S.]).

- ↑ Marcus Aurelius, "Meditations", Book I, Wordsworth Classics of World Literature, ISBN 1853264865

- ↑ Glen Newey, Routledge Philosophy GuideBook to Hobbes and Leviathan, Routledge, 2008, p. 18.

- ↑ Hilary Brown, Luise Gottsched the Translator, Camden House, 2012, p. 54.

- ↑ Two Treatises on Government: A Translation into Modern English, ISR, 2009, p. 76

- ↑ Westbrooks, Logan Hart (2008) "Personal Freedom" page 134 In Owens, William (compiler) (2008) Freedom: Keys to Freedom from Twenty-one National Leaders Main Street Publications, Memphis, Tennessee, pages 133–138, ISBN 978-0-9801152-0-8

- ↑ John Stuart Mill, On Liberty and Utilitarianism, (New York: Bantam Books, 1993), 12–16.

- ↑ "Freedom of Speech". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 17 April 2008. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/freedom-speech/#HarPriFreSpe. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ↑ A Free Digital Society - What Makes Digital Inclusion Good or Bad? by Richard Stallman - indicates some ways technology is being used which does not respect people's freedom.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 Many authors have written on this topic. One of the most well known is Lawrence Lessig (op. cit.), and see Bibliography). See also #Further reading.

- ↑ See their respective articles: knowledge and liberty and the further reading section below.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Steven Levy, 1984. Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution, Doubleday, USA. Dell, 1994, with a new afterword. Penguin Books, New York, 2001.

- ↑ See Wikipedia article hacker ethic and the section in this article on the roots of libre knowledge in libre software.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 See the section on Manifestos and Declarations in this article.

- ↑ In Further reading, see titles by Levy, Himanen, Stallman and others. Hipatia's first manifesto alludes to alchemy and modern physics.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 van Doren, M. 1954. Man's right to knowledge and the free use thereof. Columbia University, New York.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Sulzberger, Arthur Hays. 1954. Man's right to knowledge and the free use thereof, University of Hawaii Occasional Paper 61, Honolulu.

- ↑ See commons-based peer production and The Wealth of Networks by Yochai Benkler.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 For a list see Lessig Links which includes links to repositories of Lawrence Lessig's work and appearances.

- ↑ Including those which focus on software, art, music, knowledge, hardware and design, etc. or on the general issues (see #Related concepts).

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Words to Avoid (or Use with Care) Because They Are Loaded or Confusing, Richard Stallman, Free Software Foundation.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 See for example WikiEducator's justification for compromising (on libre software and file formats).

- ↑ See for example Libre Knowledge Communities and Vision in the Say Libre essay, and several works by Yochai Benkler (op. cit.) such as The Wealth of Networks.

- ↑ Fotopoulou Sophia. "The Diamond Sutra: The World's Earliest Dated Printed Book". Newsfinder. http://www.newsfinder.org/site/readings/the_diamond_sutra_the_worlds_earliest_dated_printed_book/. Retrieved 2012-03-08.

- ↑ Religious text#Views: Some religions make written texts widely and freely available, while others hold that sacred secrets must remain hidden from all but the loyal and the initiate. Most religions promulgate policies defining the limits of the sacred texts and controlling or forbidding changes and additions.

- ↑ Athanasius Letter 39.6.3: "Let no man add to these, neither let him take ought from these."

- ↑ State secrets are another example of knowledge which is not (intentionally) shared freely. An early example of this is Greek fire.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Lessig, L. 2004. Free Culture: How Big Media Uses Technology and the Law to Lock Down Culture and Control Creativity. Penguin Books.

- ↑ 1787, Article I, Section 8, Clause 8 of the United States Constitution.

- ↑ Producers include academics, educators, researchers, writers, musicians, artists, programmers, designers, etc.

- ↑ See for example Linus Torvald's book Just for Fun and Yochai Benkler's article Coase's Penguin or Linux and The nature of the firm which defines what commons-based peer production is, how it works, and what motivates contributors.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 "Would Gandhi have been a Wikipedian?". The Indian Express. 17 January 2012. http://www.indianexpress.com/news/would-gandhi-have-been-a-wikipedian/900506/0. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ↑ The free culture / libre knowledge movement covers a range of opinions on this issue ranging from copyright abolition to reform to status quo augmented with the Creative Commons licences. See Anti-copyright.

- ↑ Works include knowledge and cultural resources such as works of art, writing, education, music, software and other resources, or combinations of these, typically in digital forms which are easily copied and shared.

- ↑ In most countries "all rights reserved" is the default copyright.

- ↑ See for example History of music, Prehistoric music, Drums in communication, Folk music and related links.

- ↑ Lessig's work (2000, 2004, 2006) expands on this for all cultural works.

- ↑ Samudrala, Ram (1994). "The Free Music Philosophy". http://www.ram.org/ramblings/philosophy/fmp.html. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ↑ Nielsen Business Media, Inc. (18 July 1998). Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc.. . http://books.google.com/books?id=9wkEAAAAMBAJ. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ↑ Penenberg A. Habias copyrightus. ''Forbes'', July 11 1997. Forbes.com. Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- ↑ Durbach D. Short fall to freedom: The free music insurgency. ''Levi's Original Music Magazine'', November 19, 2008. Web.archive.org (2010-06-01). Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- ↑ Ballin M. Unfair Use. ''The Free Radical'' 47, 2001. Freeradical.co.nz. Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- ↑ Oakes C. Recording industry goes to war against web sites. Wired, June 10 1997. Wired.com. Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- ↑ Stutz M. They (used to) write the songs. Wired, June 12 1998. Freerockload.ucoz.com. Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- ↑ Napoli L. Fans of MP3 forced the issue. ''The New York Times'', December 16 1998. Nytimes.com. Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- ↑ Alternate Kinds of Freedom by Troels Just. Troelsjust.dk. Archived on 2014-09-03.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 "Hacker" refers to "someone who enjoys playful cleverness - not necessarily with computers", and is distinct from "cracker" which refers to someone who breaks security - see Words to Avoid (or Use with Care) Because They Are Loaded or Confusing (gnu.org).

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 See TMRC - Hackers.

- ↑ For the types of services see for example business model in the libre software article.

- ↑ "European Working Group on Software Libre". http://eu.conecta.it/.

- ↑ See for example, the FLOSS project, FLOSSPols, FLOSSWorld, etc.

- ↑ Most notably Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace (2000) ISBN 978-0-465-03913-5, The Future of Ideas (2001) ISBN 978-0-375-50578-2, Free Culture (2004) ISBN 978-1-59420-006-9 and Code: Version 2.0 (2006) ISBN 978-0-465-03914-2.

- ↑ Most notably 2002-07-24 "Free Culture" keynote from OSCON 2002, Wikimania and iCommons Summits.

- ↑ History of the Creative Commons.

- ↑ See for example Stop the inclusion of proprietary licenses in Creative Commons 4.0., Students for Free Culture, August 2012, and response by Timothy Vollmer.

- ↑ "History of the OSI". Opensource.org. http://opensource.org/history.

- ↑ OpenContent License (OPL) Version 1.0, July 14, 1998. Archived on 6 December 1998.

- ↑ Wiley, David. "Open Content". OpenContent.org. http://opencontent.org/definition/. Retrieved 2011-11-18.

- ↑ See for example, the guide to assessing the openness of Open Access journals, "HowOpenIsIt?", prepared by the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition and the Public Library of Science, 2014.

- ↑ Open Definition developed and maintained by the non-profit organisation Open Knowledge.

- ↑ Wheeler, David A. (2002-05-06). "Make Your Open Source Software GPL-Compatible. Or Else. (revised 2014-02-16)". http://www.dwheeler.com/essays/gpl-compatible.html. Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- ↑ "Spectrum Policy: Property or Commons?". Cyberlaw.stanford.edu. 2003-03-02. http://cyberlaw.stanford.edu/spectrum/. Retrieved 2011-01-23.

- ↑ Alesh Houdek (November 16, 2011). "Has a Harvard Professor Mapped Out the Next Step for Occupy Wall Street?". The Atlantic. http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2011/11/has-a-harvard-professor-mapped-out-the-next-step-for-occupy-wall-street/247561/. Retrieved November 17, 2011. "Lawrence Lessig's call for state-based activism on behalf of a Constitutional Convention could provide the uprooted movement with a political project for winter"

- ↑ "free_culture". Randomfoo.net. http://randomfoo.net/oscon/2002/lessig/. Retrieved 2011-01-23.

- ↑ Quote from Lessig's 2001 book, The Future of Ideas, cited in Williams, S. 2002. "Free as in Freedom: Richard Stallman's Crusade for Free Software", chapter 13, O'Reilly, CA.

- ↑ Lessig, Lawrence. "In Defense of Piracy". The Wall Street Journal. October 11, 2008.

- ↑ "The Webby Awards Gallery". 2014. http://www.webbyawards.com/winners/2014/special-achievement/webby-lifetime-achievement/lawrence-lessig. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ↑ In support of Libre Knowledge

- ↑ Hipatia.

- ↑ FreeCulture.org, Students for Free Culture chapters

- ↑ La Quadrature du Net (who we are).

- ↑ Electronic Frontier Foundation.

- ↑ "Free software is a matter of liberty, not price". Free Software Foundation. http://www.fsf.org/about/. Retrieved 2012-07-22.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions about the GNU Licenses". Free Software Foundation. https://www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl-faq.html. Retrieved 2012-07-22.

- ↑ "What Is Copyleft?". Free Software Foundation. https://www.gnu.org/copyleft/copyleft.html. Retrieved 2012-07-22.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions". Creative Commons. http://wiki.creativecommons.org/FAQ. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ Creative Commons (About).

- ↑ QuestionCopyright (About).

- ↑ Public Knowledge.

- ↑ The Center for Internet and Society at Stanford Law School.

- ↑ GNU Manifesto.

- ↑ Stallman, Richard (March 1985). "Dr. Dobb's Journal". Dr. Dobb's Journal 10 (3): 30. http://www.math.utah.edu/ftp/pub/tex/bib/toc/dr-dobbs-1980.html#10(3):March:1985. Retrieved 2011-10-18.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 109.2 109.3 Tucker, K. 2005. "Free Knowledge Communities" brochure, Meraka Institute, CSIR, South Africa.

- ↑ "Libre Communities". Free Knowledge Foundation. Archived from the original on 2008-10-10. http://web.archive.org/web/20081010204748/http://communities.libre.org/. Retrieved 2012-03-08.

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 The definition stablised into the one which appears in the Libre Declaration.

- ↑ Also known as "free content", "Libre cultural works" or simply "libre works".

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 The definitions of "libre resources" and "libre knowledge" were first formulated in 2005 in preparation for Free Knowledge Workshops convened by the Meraka Institute managed by the CSIR in South Africa and periodically refined to stabilise on this version. The definition also appears in (and is maintained on) the associated Libre Knowledge pages on WikiEducator.

- ↑ Lam, A. (2000). Tacit Knowledge, Organizational Learning and Societal Institutions: An Integrated Framework. Organization Studies 21(3), 487–513.

- ↑ See for example the section "Defining Libre Cultural Works" in the Libre Cultural Works definition.

- ↑ The Creative Commons licences disallow use of technologies which deny freedoms beyond those in the specific licence: Can I use effective technological measures (such as DRM) when I share CC-licensed material?.

- ↑ A version of the brochure for those workshops exists which may be used for education or to adapt if one feels inclined to take the ideas further: File:LibreCommunitiesBrochureForEduOrToAdapt.pdf.

- ↑ The meaning of libre or free knowledge is made clear in other sources which cover the same principles. For example, in the first Hipatia Manifesto the principles are expressed as human rights (under "proposals and actions to carry out"). An early Spanish version (2002) was archived on 5 February 2002.

- ↑ 119.0 119.1 The blog post "Misquoting Adams on the UNESCO IIEP List" alludes to these (somewhat unpopular) discussions which occurred during discussions on the UNESCO IIEP mailing lists. The discussions were summarised on the IIEP wiki.

- ↑ The term "libreware" was discussed as an alternative term for "free software" at least as far back as 2001 in the following thread: [ox-en Free Software -> Libreware or Liberation Software].

- ↑ Free content definition.

- ↑ See for example, the GNU Free Documentation License.

- ↑ Libre communities tend to avoid the word "content" and are more likely to refer to libre manuals, or libre resources, etc.

- ↑ "Free File Format Definition". LINFO.org. http://www.linfo.org/free_file_format.html. Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- ↑ Libre file format (or free file format) (WikiEducator).

- ↑ 126.0 126.1 On account of restrictions certain standards bodies impose on the use of standards, some libre communities, most notably the free software community, avoid the term "standard" and refer instead specifically to free or libre file formats and protocols. In cases where a libre format or protocol has become a de facto "standard", extensions and variations should be clearly indicated so that the resulting format is clearly distinct from that standard.

- ↑ The concept of free/libre network services is explored on the autonomo.us wiki.

- ↑ Franklin Street Statement on Freedom and Network Services.

- ↑ All of the designs produced by the project are released under a libre software licence, the GNU General Public License: http://reprap.org/wiki/RepRapGPLLicence RepRap licence page.

- ↑ See the proposed Open Source Hardware (OSHW) Definition.

- ↑ For example (see the OpenCollector's "License Zone"), the GNU General Public License is used by the Free Model Foundry and OpenSPARC; other licenses are (or were) used by the Free-IP Project and LART (the software is released under the terms of the GNU General Public License, and the Hardware design is released under the MIT License).

- ↑ Examples include the TAPR Open Hardware License, the CERN Open Hardware License and the Solderpad License.

- ↑ TAPR Open Hardware License

- ↑ Defensive Patent License Launch.

- ↑ The Defensive Patent License (DPL).

- ↑ See for example Libre Hardware, Libre3D, Libre Hardware Network and Purism Librem 15 Laptop.

- ↑ Hardware Devices that Support GNU/Linux

- ↑ The article Who does that server really serve? outlines the concerns from the point of view of the libre software community.

- ↑ 139.0 139.1 See for example Proprietary Software Is Often Malware.

- ↑ Antifeatures by Benjamin Mako Hill.

- ↑ List of antifeatures

- ↑ 142.0 142.1 See for example Fighting Software Patents - Singly and Together by Richard Stallman

- ↑ 143.0 143.1 See for example, La Quadrature du Net's page on Net Neutrality.

- ↑ 144.0 144.1 Lawrence Lessig and Robert W. McChesney (8 June 2006). "No Tolls on The Internet". Columns. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/06/07/AR2006060702108.html.

- ↑ Lessig, L. 1999. Cyberspace’s Architectural Constitution, draft 1.1, Text of lecture given at www9, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- ↑ Debate over the issue of net neutrality pre-dates the coining of the term by Columbia University media law professor Tim Wu in 2003 (see main article Net neutrality).

- ↑ Free Culture Forum, 2009. FCF developed the Charter for Innovation, Creativity and Access to Knowledge. A Libre Interpretation was also prepared which focuses on education and orientates towards sustainability as a goal. A version of the latter using the word "free" rather than "libre" is available on the Free Knowledge Institute wiki.

- ↑ Digital Restrictions Management. DRM.info. Retrieved on 2013-07-29.

- ↑ What is DRM?. Defective by Design. Retrieved on 2013-07-29.

- ↑ GNU Art - Digital Restrictions Management - GNU Project - Free Software Foundation. Gnu.org (2013-02-28). Retrieved on 2013-07-29.

- ↑ Rick Falkvinge (14 July 2013). "Language Matters: Framing The Copyright Monopoly So We Can Keep Our Liberties". Archived from the original on 4 June 2014. http://web.archive.org/web/20140604193406/http://torrentfreak.com/language-matters-framing-the-copyright-monopoly-so-we-can-keep-our-liberties-130714/. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- ↑ "Apple's Operating Systems Are Malware". Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. http://web.archive.org/web/20140716090458/https://www.gnu.org/philosophy/proprietary/malware-apple.html. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ↑ 153.0 153.1 Emerging Policy Issues in Synthetic Biology (Google eBook), OECD, 2014.

- ↑ Bügl, H. et al. (2007). "DNA synthesis and biological security". Nature Biotechnology 25 (6): 627–629. . http://www.nature.com/nbt/journal/v25/n6/full/nbt0607-627.html.