Time and motion

| Art Appreciation and Techniques (#ART100) | |

|---|---|

| The visual language: Artistic principles | Overview | Introduction | Visual balance | Repetition | Scale and proportion | Emphasis | Time and motion | Unity and variety | Summary |

An early example of this is in the carved sculpture of Kūya, shown at left. The Buddhist monk leans forward, his cloak seeming to move with the breeze of his steps. The figure is remarkably realistic in style, his head lifted slightly and his mouth open. Six small figures emerge from his mouth, visual symbols of the chant he utters.[1]

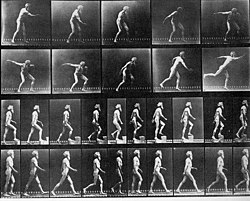

In the modern era, the rise of cubism (discussed earlier in our study of space) and subsequent related styles in modern painting and sculpture had a major effect on how static works of art depict time and movement. These new developments in form came about, in part, through the cubist’s initial exploration of how to depict an object and the space around it by representing it from multiple viewpoints, incorporating all of them into a single image. Marcel Duchamp’s painting Nude Descending a Staircase from 1912 formally concentrates Muybridge’s idea into a single image. The figure is abstract, a result of Duchamp’s influence by cubism, but gives the viewer a definite feeling of movement from left to right. This work was exhibited at The Armory Show in New York City in 1913. The show was the first to exhibit modern art from the United States and Europe at an American venue on such a large scale. Controversial and fantastic, the Armory Show became a symbol for the emerging modern art movement. Duchamp’s painting is representative of the new ideas brought forth in the exhibition.

The temporal arts of film, video and digital projection by their definition show movement and the passage of time. In all of these mediums we watch as a narrative unfolds before our eyes. Film is essentially thousands of static images divided onto one long roll of film that is passed through a lens at a certain speed. From this apparatus comes the term ‘movies’.

Video uses magnetic tape to achieve the same effect, and digital media streams millions of electronically pixilated images across the screen. An example is seen in the work of Swedish Artist Pipilotti Rist. Her large-scale digital work Pour Your Body Out is fluid, colorful and absolutely absorbing as it unfolds across the walls.

Notes

- ↑ More about Kuya-Shonin in Art Through Time at Annenberg Learner.

- ↑ More about Bernini's David at Galleria Borghese.