Modern variations

| Art Appreciation and Techniques (#ART100) | |

|---|---|

| Artistic media: Three-dimensional art | Overview | Introduction | Sculpture and other three-dimensional media | Methods | Modern variations | Summary |

Installation Art

Installation art utilizes multiple objects, often from various mediums, and takes up entire spaces. It can be generic or site specific. Because of their relative complexity, installations can address aesthetic and narrative ideas on a larger scale than traditional sculpture. Its genesis can be traced to the Dada movement, ascendant after World War I and which predicated a new aesthetic by its unconventional nature and ridicule of established tastes and styles. Sculpture came off the pedestal and began to transform entire rooms into works or art. Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau, begun in 1923, transforms his apartment into an abstract, claustrophobic space that is at once part sculpture and architecture. With installation art the viewer is surrounded by and can become part of the work itself.

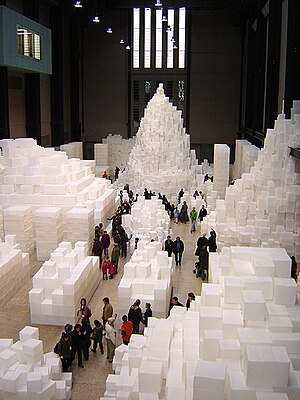

British artist Rachel Whiteread’s installation Embankment from 2005 (image shown at right) fills an entire exhibition hall with casts made from various sized boxes. At first appearance a snowy mountain landscape navigated by the viewer is actually a gigantic nod to the idea of boxes as receptacles of memory towering above and stacked around them, squeezing them towards the center of the room.Ilya Kabakov mixes together a narrative of political propaganda, humor and mundane existence in his installation The Man Who Flew Into Space From His Apartment from 1984. What we see is the remains of a small apartment plastered with Soviet era posters, a small bed and the makeshift slingshot a man uses to escape the drudgery of his life within the system. A gaping hole in the roof and his shoes on the floor are evidence enough that he made it into space.

Performance Art

Performance art goes a step further, involving the artist as part of the work itself. Some performance artworks are interactive, involving the viewer too. The nature of the medium is in its ability to use live performance in the same context as static works of art: to enhance our understanding of artistic experience. Similar to installation works, performance art had its first manifestations during the Dada art movement, when live performances included poetry, visual art and music, often going on at the same time.

The German artist Joseph Beuys was instrumental in introducing performance art as a legitimate medium in the post World War Two artistic milieu. I Like America and America Likes Me from 1974 finds Beuys co-existing with a coyote for a week in the Rene Block Gallery in New York City. The artist is protected from the animal by a felt blanket and a shepherd’s staff. Performance art, like installation, challenges the viewer to reexamine the artistic experience from a new level.In the 1960’s Allen Kaprow’s Happenings invited viewers to be the participants. These events, sometimes rehearsed and other times improvised, begin to erase the line between the artist and the audience. Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece from 1965 specifically invites members of the audience to interact with her on stage.

This same idea – using the artist’s body as subject, is evident in the performance art of Marina Abramovic. In The Artist is Present she sits quietly as individual visitors sit across the table from her, exchanging silent glances and stares.

Today we see a new form of performance art happen unexpectedly around us in the form of flash mobs: groups of people who gather in public spaces to collaborate in short, seemingly spontaneous events that entertain and surprise passersby. Many flash mobs are arranged in advance through the use of social media. An example of flash mob performance is Do Re Mi in the Central Station in Antwerp, Belgium in March of 2009.

Decorative Arts

Decorative art requires the specific skilled use of tools in creating works or art. These tools can take many forms: words, construction tools, a camera, a paintbrush or even a voice. Traditional studio arts include ceramics, metal and woodworking, weaving and the glass arts. Decorative arts are distinguished by a high degree of workmanship and finish. They have their roots in utilitarian purposes: furniture, utensils and other everyday accoutrements that are designed for specific uses, and reflect the adage that “form follows function”. But human creativity goes beyond simple function to include the aesthetic realm, entered through the doors of embellishment, decoration and an intuitive sense of design.

In the first example below, the smooth simple lines of a Tulip Chair, were designed by Eero Saarinen as an exercise in clarifying form. When it was made its futuristic use of curved lines and artificial materials were seen as emblematic of the “space age.” In another example, a staircase crafted in the Shaker style takes on an elegant form that mirrors the organic spiral shape representing the ‘golden ratio’, which we explored in visual balance, one of the Artistic Principles.

As we’ve seen in an earlier module, quilts made in the rural community of Gee's Bend Alabama, in the southern United States, show a diverse range of individual patterns within a larger design structure of colorful stripes and blocks, and have a basis in graphic textile designs from Africa.

Even a small tobacco bag from the Native American Sioux culture (at left) becomes a work of art with its intricate beaded patterns and floral designs.The craftsmanship in glass making is one of the most demanding. Working with an extremely fragile medium presents unique challenges. Challenges aside, the delicate nature of glass gives it exceptional visual presence. A blown glass urn dated to first century Rome (below, left) is an example. The fact that it has survived the ages intact is testament to its ultimate strength and beauty.

Louis Comfort Tiffany introduced many styles of decorative glass between the late 19th and first part of the 20th centuries. His stained glass window The Holy City in Baltimore, Maryland (below, right) has intricate details in illustrations influenced by the Art Nouveau style popular at the turn of the 19th century.

The artist Dale Chihuly has redefined the traditional craft of glass making over the last forty years, moving it towards the mainstream of fine art with single objects and large scale installations involving hundreds of individual pieces.

Product Design

The dictum “form follows function” represents an organic approach to three-dimensional design. The products and devices we use everyday continue to serve the same functions but change in styles. This constant realignment in basic form reflects modern aesthetic considerations and, on a larger scale, become artifacts of the popular culture of a given time period.

The two examples below illustrate this idea. Like Tiffany glass, the chair designed by Henry van de Velde in 1895 (below, left) reflects the Art Nouveau style in its wood construction with organic, stylized lines and curvilinear form. In comparison, the Ant Chair from 1952 (below, right) retains the basic functional form with more modern design using a triangular leg configuration of tubular steel and a single piece of laminated wood veneer, the cut out shape suggesting the form of a black ant.

|

Installation and Performance Art Since the 1960s, installation and performance art have taken their place alongside traditional sculpture. In some ways, installation and performance art have eclipsed traditional sculpture as the most significant contemporary three-dimensional art form.

Write your objective and subjective responses to the works, keeping in mind the context of the medium itself. How does performance and installation art expand our experience about what art is? Whether you like or dislike the works here, write about what makes these art forms unique.

|