The Copyright Challenge

Do we do what it takes to change the law, or work around it without breaking it?

Contents

The Copyright Barrier

De facto copyright law, as currently framed, is a barrier to achieving the vision of the OER movement.

Images, videos, podcasts, and pages that are accessible on the Internet, are more often than not, copyrighted. This means that it may not be legal for you to download them, use them or adapt them for the needs of your students, or redistribute them to your students.

The default legal situation in most countries is that the original author holds an "all rights reserved" copyright on their work, unless:

- contracted otherwise by their employment agreement where materials developed at work belong to the employer;

- or in cases where the author declares that the work will be released under public domain.[1]

An "all rights reserved" copyright means that you cannot use, adapt or redistribute these materials without the express permission of the copyright holder.

Downloading and using an image from a news site without the owner's permission may seem harmless, but it can expose you and your institution to liability.

Furthermore, if you plan on sharing your OER with others, most online sites like Youtube and Flickr will remove material from their websites if they receive a copyright or ownership-related complaint. That means all your work may be at risk of being deleted if you incorporate someone else's copyrighted material into your work.

Changing copyright law from the top down (not through lack of solid arguments) has proven extremely difficult, and will take time.

In the meantime, we can continue to produce useful learning and knowledge resources by working around the issue. Demonstrating the value of sharing to society will help persuade "the powers that be" to consider re-framing copyright law to make more sense in the connected "copy-modify-mix-and-share" world.

Copyright Workaround and Opportunities

The difficulty with copyright law as currently framed has been raised before in the free software world and more recently by the free culture movement.

The Free Software movement, concerned about losing the freedom to help your neighbor and community by cooperating on software development, produced the GNU General Public License (GNU GPL)[2] for software which cleverly uses copyright against itself ("copyleft"). The author (and copyright holder) has the right to specify how the work may be used. By releasing the work under the GNU GPL the author is granting users the freedom to use, adapt, enhance and share the work provided the results are shared under the same license - perpetuating the freedoms ("copyleft"). In a similar vein, they also produced the GNU Free Documentation License[3] for manuals, textbooks, or other functional and useful documents.

The free culture movement has produced a suite of "Creative Commons" licenses enabling authors to decide which rights to retain and which to give away ("some rights reserved").

In effect, we can work around copyright law and continue on our open education mission towards education for all. Each teacher, lecturer or trainer is the default copyright holder of the materials they produce. These authors are free to license the use and reuse of the materials as they see fit. For OER this means sharing their materials so that other people can use them freely without needing to ask for permission.

Because most OER have copyright licenses that are purposefully designed to give you permission to download, alter, and share them, OER provide an exciting opportunity for creating and sharing educational materials in your classroom, with your colleagues, and with the world at large.

I suggest moving the rest into the licensing section.

What about Fair Use?

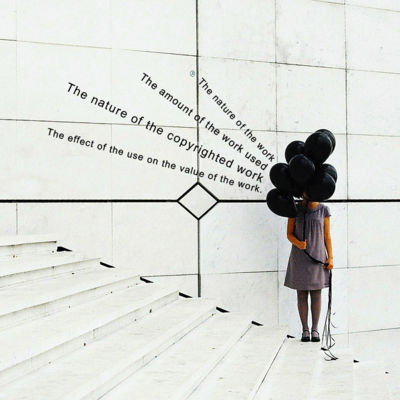

Fair use is a doctrine in U.S. copyright law (called Fair dealing[4] in most countries outside the U.S.) to allow for select uses of copyrighted material without the copyright holder's consent under certain conditions. Fair use is open to interpretation and there are no concrete rules regarding fair use. Furthermore, the interpretation of fair use (or fair dealing) may differ across national jurisdictions, but here are a few ways in which it is typically measured:

- The nature of the work. That means whether or not it is being used for a non-commercial purpose. When something copyrighted is used in a non-commercial way, it is more likely to be considered fair use.

- The nature of the copyrighted work. The more useful something is to the common good, the more likely it will be considered fair use. For example, a paragraph about fire safety tips is less protected than a popular song.

- The amount of the work used. The less you use of a copyrighted material, the more likely it will be considered fair use. As an example, 30 seconds of a movie might be considered fair, while 30 minutes would not.

- The effect of the use on the value of the work. The more the use diminishes the value of the original work, the less likely the use is to be ruled fair use. (U.S. Copyright Office, 2006)

Unfortunately, fair use is often unclear and difficult to determine. So for example, while it may be fair use to show a magazine advertisement in your class when teaching a lesson on the social impacts of advertising -- it may not be fair use to make a digital copy of the advertisement for a slide show presentation and then upload your teaching resource on a public website.

Copyright laws also vary from country to country, so it is a good idea to check with local laws and regulations regarding copyright. Use OER and bypassing the worry altogether is a good option!

But I'm using it in a classroom, isn't that fair use?

Fair use protects many uses in the classroom. The problem comes when you want to share these great materials you've made with others, for example online. Fair use does not protect you when placing educational materials online, because you're outside your classroom. Because educators are not protected when sharing online, many opt to put their material on a private site behind a password (perhaps in a system like Moodle, Blackboard, or Angel), which in many situations would not be covered under fair use.

While fair dealing may be assist your teaching in the classroom, it is still a barrier to sharing knowledge. Potential audiences, such as family members and others in the community, will not be able to access the materials. There is also the difficulty of administering passwords and access. Most importantly, creating new lesson materials or adapting someone else's work is time-consuming. Sharing materials brings value to many other educators, but inappropriate licensing can make legally sharing educational resources online difficult, if not impossible.

More information on copyright

- Cornell's Copyright Information Center[5]

- Information on the TEACH Act[6] which updates copyright law with regards to online education)

- COL resources on copyright[7]

- Brief History of Copyright.

Sources

U.S Copyright Office.(Last Updated 2006, July). Fair Use. Retrieved March 21, 2008, from http://www.copyright.gov/fls/fl102.html

Wiley, D. (2007, August). Open education license draft. Iterating Towards Openness. Retrieved March 28, 2008, from http://opencontent.org/blog/archives/355

Notes etc.

- ↑ Note that public domain is not a legal license -- but a declaration to release cultural works as a contribution to the intellectual commons.

- ↑ http://www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl.html

- ↑ http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fair_dealing

- ↑ http://www.copyright.cornell.edu/

- ↑ http://www.lib.ncsu.edu/scc/legislative/teachkit/

- ↑ http://www.col.org/colweb/site/pid/3977