Brief History of Copyright

Contents

Copyright

A work in progress, please comment and help improve this table.

The table below, drawn up from some of the writings of Lessig[1][2][3][4], Benkler[5] and Aigrain[6]. Ghosh (2005)[7], summarises the history of copyright indicating how the freedom to adapt and share has been progressively taken away since the invention of the printing press.

| 1662 | Licensing Act passed: regulated publishers, giving them a monopoly, so that the Crown could have some control over what was published. Expired in 1695. |

| 1710 | Statute of Anne, the first “copyright” act, adopted by British Parliament. Copyright term: 14 years, optionally renewable by the author for an additional 14. Previously published works covered by copyright for 21 years from 1710. Restricted the right to copy a particular book to a particular machine. |

| 1731 | Romeo and Juliet should have entered the public domain. However, there was still an issue in 1774 as common law seemed to indicate that copyrights are perpetual. |

| 1774 | House of Lords voted against perpetual copyrights – the public domain was born, and culture freed. |

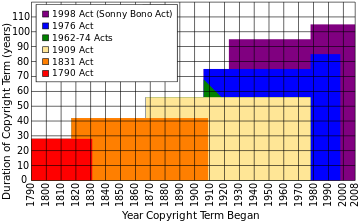

| 1790 | Copyright Act of 1790 [8] .... By now many states had passed laws protecting creative property.[9]. Copyright covered only “maps, charts, and books.”[10] |

| 1831 | Copyright extended to cover music, and the initial term was lengthened to 28 years (still optionally renewable for another 14 years). |

| 1870 | Copyright extended to apply to paintings, statues, and derived works such as translations and dramatisations. |

| 1909 | A semantic error in a statute extended copyright beyond “publish” and “re-publish” to the right to “copy”. Renewal period lengthened from 14 to 28 years to give a possible total of 56 years. |

| 1928 | Mickey Mouse born. Should be free in 1984 (1928 + 56). |

| 1962 | The practice of extending existing copyrights starts - mostly short extensions of a few years for existing copyrights, and occasionally of future copyrights. |

| 1970s | Photocopiers became widely accessible and became the target of “extensive litigation”. |

| 1976 | All existing copyrights extended by nineteen years. |

| 1976 | Renewal requirement dropped: for works created after 1978 the maximum term available applied (life plus 50 years for “natural” authors, and 75 years for corporations). |

| 1976- | To simplify copyright law, amendments were made leading to the current situation of all works being automatically covered (© all rights reserved). |

| 1988 | Copyright Term Extension Act (also known as the "Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act", "Sonny Bono Act", or pejoratively as the "Mickey Mouse Protection Act"[11]), extended the 1976 terms to life of the author plus 70 years and for works of corporate authorship to 120 years after creation or 95 years after publication, whichever endpoint is earlier[12]. Copyright protection for works published prior to January 1, 1978, was increased by 20 years to a total of 95 years from their publication date. |

| 1992 | Renewal requirement dropped for all works created before 1978 that were still under copyright: ninety-five years after the Sonny Bono Act. |

| 1998 | Existing and future copyrights extended for 20 years - Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act (see Lessig, 2004, 134). |

Currently, in most countries, the default copyright (if nothing to the contrary is indicated in the work) is all rights reserved for the author, apparently indefinitely. Many publishers require authors to sign over that all-encompassing copyright to them, e.g.

Copyright © 2007 <author name>All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed ... [in any way whatsoever] ... without the prior written permission of the publisher ....

though this can often be negotiated. In the modern connected world, this situation generally restricts progress, contradicting the original purpose of copyright: to promote progress in science and the useful arts - a public good. The purpose is not to enrich publishers or authors, or to grant them undue influence on development and distribution of culture (Lessig, 2004).

The effect is a severe restriction of the growth of the knowledge commons, and of the flow of creativity that supplies the publicly available pool of cultural resources.

Free software guru Richard Stallman claims that in the age of the digital copy the role of copyright has been completely reversed. While it began as a legal measure to allow authors to restrict publishers for the sake of the general public, copyright has become a publishers’ weapon to maintain their monopoly by imposing restrictions on a general public that now has the means to produce their own copies.

Reforming copyright law is one approach to correcting this situation. There are efforts to do so, but the task has proved extremely challenging on account of strong lobbying on the part of publishers and media companies with a vested interest in the traditional property-based approach.

In the meantime, there are some work-arounds: copyleft (Free Software Foundation) and some of the Creative Commons licenses.

See Also

- History of copyright - straw dog for Copyright for Educators/History

- Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States.

- Say Libre - this page was originally prepared in preparation for the "Say Libre" essay.

- Copyrights

Links etc.

| History of copyright law | |

| Wikipedia has an article on this subject.

Visit History of copyright law for more in depth information |

- Misinterpreting Copyright - A Series of Errors.

- QuestionCopyright.org - whose mission is "to educate the public about the history of copyright, and to promote methods of distribution that do not depend on restricting people from making copies".

- w:History of copyright law.

- A Brief History of Copyright and Innovation.

- Free Culture - Lawrence Lessig Keynote from OSCON 2002 on the current state of intellectual property and its ramifications on creativity and culture.

- Time to update copyright law? - By William Patry, Special to CNN January 31, 2012 - Updated 2130 GMT (0530 HKT).

- Center for the Study of the Public Domain - CSPD Duke University School of Law

- See CSPD Comics: Tales from the Public Domain: BOUND BY LAW?

Readings

- ↑ Lessig, L. 2000. Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace, Basic Books, New York.

- ↑ Lessig, L. 2001. The Future of Ideas, Random House, New York.

- ↑ Lessig, L. 2004. Free Culture. Penguin Press, New York.

- ↑ Lessig, L. 2006. Code 2.0, Basic Books, New York.

- ↑ Benkler, Y. 2006. The Wealth of Networks, Yale University Press, London.

- ↑ Aigrain, P. 2005. Positive intellectual rights and information exchanges, in Ghosh (2005)

- ↑ Ghosh, R. A. 2005. Cooking-pot markets and Balanced Value Flows. In Ghosh, R. (editor) CODE, MIT Press, 2005.

- ↑ http://www.iprightsoffice.org/copyright_history/

- ↑ Citation in Lessig 2004, see p133

- ↑ Lessig, L. 2005. The People Own Ideas! NetPlus, 12, August/September, Intelligence Publishing, Cape Town.

- ↑ Lawrence Lessig, Copyright's First Amendment, 48 UCLA L. Rev. 1057, 1065 (2001)

- ↑ U.S. Copyright Office, Circular 1: Copyright Basics, pp. 5-6