Complex Research Designs

| Unit 4: Experimental Research Methods | |

|---|---|

| Experimental Research Methods | Unit 4 Overview | Unit 4 Outcomes | Unit 4 Resources | Basics of Experimental Research | Complex Research Designs | Single-Subject Research | Activities and Assessments Checklist |

Complex Designs

Studies with complex designs investigate the effects of more than one variable. For example, we may want to study the effects of a new cognitive therapy and a drug treatment on depression. We might employ what is referred to as a 2 × 3 factorial design to assess these treatments for depression. These designs are referred to as multi‐factorial or complex designs because they are concerned with more than one factor (such as drug and cognitive treatments). The 2 × 3 (referred to as “two by three”) refers to the number of factors and the number of levels of each factor. Therefore, a 2 × 3 study has two factors (indicated by the two numbers), one with two levels and the other with three levels. For example, in a 2 × 3 study, one might recruit 120 depressed patients. Sixty would receive the cognitive treatment and the remaining sixty would not receive it. For each group of sixty, twenty would not receive a drug, twenty would receive a low dose of the drug, and twenty would receive a high dose. Therefore, there would be a total of six groups.

This study of depression could be expanded to include additional factors. If we were to expand the study to include a third type of treatment, for example, four different nutritional supplements, we would have a 2 × 3 × 4 factorial design. In a 2 × 3 × 4 design on depression, we might have three treatments (such as cognitive, drug, and nutrition) with the first factor having two levels (such as presence or absence of cognitive therapy), the second factor having three levels (for example, no drug, low dose, high dose), and the third factor having four levels. The study would then have a total of twenty‐four groups.

There are several benefits of complex designs. First, the world we live in is complex; it involves many different factors. Therefore, complex designs may be more valid because they more closely approximate our complicated world than designs that only study individual factors in isolation. Second, they allow for the study of interactions. Interactions occur when the effect of one factor is influenced by another factor. For example, maybe cognitive therapy alone has no effect on depression, but, when combined with a high dose of a drug, it alleviates depression more effectively than the drug alone. Third, complex designs are more efficient because they better utilize the researcher’s limited resources. For example, if a researcher were interested in two factors and studied them in two separate studies, he or she would need a control group that received no treatment in each study (a non‐treated group would have to be included in both studies). This would be more time consuming, more expensive, and would potentially expose more participants to any potential negative side effects of the treatment condition.

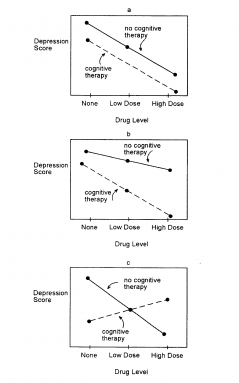

As mentioned, an important aspect of complex designs is that they allow the researcher to assess interactions. An interaction is when the effect of one variable depends on the level of another variable. Three possible results from a hypothetical 2 × 3 study on the effects of cognitive therapy and drugs on depression are shown in Figure 4-1.

In Figure 4-1(a), no interaction is present. Increasing drug doses decreases depression and cognitive therapy decreases depression. However, the effect of one factor does not influence the effect of the other factor. Note that the lines illustrated on the graph are parallel. This indicates that no interaction is present. Figure 4-1(b) illustrates an interaction. The effect of the drugs depends on whether or not cognitive therapy is given. Drugs have a small effect on their own but a much larger effect when given in conjunction with cognitive therapy. Note that the lines are not parallel, indicating the presence of an interaction. The effectiveness of drug therapy depends on whether cognitive therapy is applied. Figure 4-1(c) also indicates an interaction. Drugs decrease depression when they are the only treatment, but when cognitive treatment is applied, drugs actually increase depression. Note that the lines intersect. This interaction, when the lines cross each other, is referred to as a cross‐over interaction.