The Waikato Wars (1863-64)

| [▲]The New Zealand Wars | ||

|---|---|---|

| The Waikato Wars (1863-64) | Introduction | Koheroa | Camerontown | Pukekohe East | Titi Hill | Meremere | Rangiriri | Paterangi | Rangiaowhia | Hairini | Orakau | Gate Pa | Te Ranga | |

Contents

[hide]- 1 Introduction

- 1.1 Koheroa (17th July 1863)

- 1.2 Camerontown (7th September 1863)

- 1.3 Alexandra Redoubt

- 1.4 Pukekohe East (14 September 1863)

- 1.5 Titi Hill/Mauku (23 October 1863)

- 1.6 Meremere (31 October 1863)

- 1.7 Rangiriri (20 November 1863)

- 1.8 Paterangi and Rangiatea (February 1864)

- 1.9 Rangiaowhia (21st February, 1864)

- 1.10 Hairini (22 February 1864)

- 1.11 Orakau (31st March-2nd April 1864)

- 2 Tauranga (1864)

- 3 Fortifications

Introduction

- Naval vessels of the New Zealand Wars

On July 9th Governor George Grey ordered all Maori living between Auckland and Waikato to move south of the river. On 17 July, 553 of Grey's men under the command of General Cameron moved from Queen's Redoubt Pokeno to attack a small Maori force at Koheroa,[1] beginning the Waikato Wars. Defences around Auckland were also strengthened, with things like the Onehunga Blockhouse (1860) and the Great South Road begun (December 1861). The invasion of the Waikato begun in earnest when General Cameron crossed the Mangatawhiri stream on 12th July 1863, establishing a small camp inside the Kingitangi controlled land in North Waikato.

Koheroa (17th July 1863)

The first event of the Waikato war was a small skirmish that took place on the 17th of July 1863. Somewhere between 100-150 Maori were preparing fortifications on the hill overlooking the Mangatawhiri stream when they were attacked by Cameron's men. After a brief skirmish, the Maori fell back to Whangamarino and Meremere.

Camerontown (7th September 1863)

On the morning of the 7th September 1863, around 100 mostly Ngati Maniapoto warriors came downstream from near Rangiriri and attacked the small settlement of Camerontown. It was established in order to get supplies up the Waikato river, but after the ambush, the stores depot was captured and over 40 tons of supplies burned.

Alexandra Redoubt

Alexandra redoubt is north of the Mangatawhiri stream and was established here in July 1863 because it gave good views of the Waikato river to both the north and south. Camerontown (further to the south) was attacked in September 1863 which meant that river transport couldn't be relied upon to provision the troops deeper into the Waikato.

Pukekohe East (14 September 1863)

This church was turned into a stockade and protected by the European settlers around Pukekohe during 1863. The stockade was built out of logs from the surrounding bush, 6 inches thick and about 7 feet high. The church was attacked on the 13th September 1863. Four men were surprised by a group of Maori; two ran for the stockade and made it inside; two ran for the bush and were separated from their colleagues for most of the day. Both managed to re-enter the stockade at night despite Maori lighting fires in the fern to illuminate them as they returned. The defence of the stockade continued in earnest the following day with 'scores' of (possibly up to 200) Maori attacking the small church. It was successfully defended over the course of the day

Titi Hill/Mauku (23 October 1863)

The sound of gunfire attracted the attention of the Forest Rifles and Militia stationed at the Mauku church, who then scouted through the bush towards the noise. They saw a group of Maori shooting cattle on Wheeler's farm near Titi Hill. A small force of around a dozen men attempted to approach the Maori but were in turn encircled and fired upon in a fierce exchange of weapons at close quarters in half-cleared bush. 8 British and (Cowan estimates) around 30 Maori were killed. Titi Hill/Mauku fits the pattern of a guerrilla attack, designed to disrupt the European advance into the Waikato.

Meremere (31 October 1863)

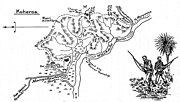

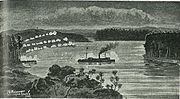

The Kingitanga troops had fortified Meremere pa with earthworks and 15 foot high palisades, and had even carried three ships guns from the West Coast to shore up defences. On the 29th October the gunboat 'Pioneer' anchored 300m from the river shore and traded bombardments with the Maori cannon. Meremere was also fired upon from the British position at Whangamarino. On the two following days this pattern was repeated, although on the 30th the Rangiriri was hit by the upper gun, with the projectile landing in a barrel of salted pork. On the 321st, a force of around 600 British soldiers was landed upstream and they began their attack on the pa. After nightfall, the Kingitanga troops withdrew from Meremere by way of the swampy ground at the rear of the pa, their purpose apparently to slow the British advance so that the fortification of Rangiriri could be completed.

Rangiriri (20 November 1863)

One of the major turning points in New Zealand history took place at Rangiriri over three days in November 1963. On the 20th, 6 armoured vessels anchored adjacent to the impressive fortifications and began a two hour bombardment of them. Thinking that the earthworks had suffered enough to allow an assault of the pa, Cameron ordered the 65th Regiment to attack using scaling ladders and planks. They made progress initially. capturing the outer defences and forcing the Maori defenders into the central redoubt which towered some 18 feet above the trenches. General Cameron made successive attempts to attack the central redoubt, all of which failed with considerable losses. Hostilities ceased lessened after nightfall, but during the night Maori taunted the British with shouting and haka from the redoubt. Near dawn, an attempt was made to dig under the fortifications and lay mines, but this failed due to the fuses being mislaid aboard the Pioneer. Also during the night, many Maori escaped across Lake Waikare to fight another day. Shortly after dawn, Maori raised a white flag of truce. Believing they had surrendered, the British entered the fortress and took prisoner the 183 Maori who remained. This proved to be a devastating blow to the Kingite movement, with 175 firearms surrendered as well as many prominent rangatira captured.

- As a sidenote, the Rangiriri prisoners were imprisoned on a hulk in Auckland harbour before being moved to Kawau island. On 11th September 1864 they took all of the boats they could find and, using spades and shovels, paddled their way across to Waikauri. They established a camp at Otamahua before heading to the Kaipara and thence back to the Waikato; their arrival too late to assist in the remainder of the Waikato wars.

Paterangi and Rangiatea (February 1864)

After the fall of Rangiriri, Waikato Maori began work on an enormous series of earthworks at Paterangi and Rangiatea, north west of Te Awamutu. The Paterangi fortifications covered about 2 acres and included two ships' guns carried overland from Kawhia Harbour. It was made up of three strong central redoubts surrounded by a series of tunnels and trenches. One of these trenches was 100 yards long and protected a deep well. Rangiatea to the south, covered the rear of Paterangi and both were designed to protect the productive jewel of Rangiaowhia. In the end, neither of these fortifications were employed in battle, as General Cameron outflanked these defences and struck directly Rangiaowhia.

Rangiaowhia (21st February, 1864)

At 10pm on the 20th February, 1864 almost a thousand men began marching from Te Rore towards Rangiaowhia. In doing so, they were bypassing the impressive fortifications at Paterangi in order to attack the softer target of Rangiaowhia, which boasted fields of wheat, maize and potatoes, peach groves, thatched houses, two churches, flour mills, stores, schools, and even a race course. The attack took the Maori by surprise, with many of them retreating into their poorly reinforced houses and huts in a vain attempt to return fire. One of the raupo whare had an excavated floor which offered Maori a good position from which to fire. Despite being pinned down, they managed to kill several British soldiers including Colonel Nixon. The British set fire to many of the whare and shot the inhabitants when they tried to escape. One kaumatua emerged from the whare, his empty hands above his head holding only a white blanket. Despite officers calling 'Spare him, spare him!' he was shot by a number of British troopers. In total about a dozen houses were burnt and a similar number of Maori killed. The British lost 5 troopers.

Hairini (22 February 1864)

Orakau (31st March-2nd April 1864)

Orakau, like Rangiaowhia was 'an idyllic home for Maori... it was a garden of fruit and root crops. On its slopes were groves of peaches, almonds, apples, quinces and cherries; grape-vnes climbed the trees and the thatched raupo houses. Potatoes, kumara, maize, melons, pumpkins and vegetable marrows were grown plentifully. Good crops of wheat were grown in the fifties and sixties on the northward sloping ground” [2] It was in a grove of these peach trees that a fort was established by Tuhoe and Ngati-te-Kohera for the defence of Orakau. The low earthworks outside and bunkers inside the pa were constructed in relays because there were not enough spades available. The 300 people (including about 20 women and some children) who defended the pa under the leadership of Rewi Maniapoto were short of rifles and ammunition. On 31st March 1863, the first British attack was made on the still-incomplete defences. The Forest Rangers, including Major von Tempsky battled with the defenders through the morning before reinforcements (Ngati Haua, Ngati Raukawa and other iwi) arrived. Fighting continued through the afternoon and overnight, with the British troops bolstered to a size of almost 1500 men. After dawn on the second day, the Maori defenders acknowledged that their powder and ammunition was running low. The heavy fog of the morning burnt off and as the day got hotter, the warriors' water supplies were depleted to nothing. In the afternoon, Maori launched a spirited charge out of the pa and 200 metres into British lines before retreating again. As afternoon drew into evening, and with Maori reduced to firing peach pits from their muskets, it became clear they needed to do something to break out of their dire situation. On the morning of the third day, the decision was made to abandon the pa. British sappers had been digging a trench that now almost reached the outer defences of the pa, and with no water and little powder left, Rewi Maniapoto and the other rangatira decided a kotiri (charge) out of the pa was the only option. After burying their dead in the trenches around the pa, loading their muskets with any remaining powder and arming themselves with long-handled tomahawks the defenders of Orakau broke free from the pa and made for a swamp to the east of their position. Fierce firing broke out as the British realised what was happening and many Maori were killed, although dozens, including Rewi Maniapoto, managed to escape. In all around 160 Maori were killed to 17 British, and Orakau marked the end of hostilities in the heart of the Waikato. Only two more battles occurred in what has come to be know as the Waikato Wars, but Gate Pa and Te Ranga are really wars of the Bay of Plenty that happened to involve warriors from the Waikato. In general, Maori tactics would change to more of a guerilla style of fighting; striking hard, then disappearing into the bush. Warrior leaders and prophets like Te Kooti, Titokowaru, Te Whiti-o-Rongomai, Tohu Kakahi and Rua Kenana would now take up the cause of Maori resistance to European control of their land and destiny.Tauranga (1864)

Gate Pa (28 April 1864)

Following closely on the European victory at Orakau, Gate Pa was a demoralising rout for the British. 230+ Maori concealed in the low pa were pounded by artillery in the afternoon of the 28th April 1864[3]. The following day, at 4pm, 300 European soldiers charged the pa. Maori hidden in the pa's network of bunkers and tunnels opened fire and inflicted considerable numbers of casualties on the attacking force. All told, 35 Europeans were killed and 75 wounded. Maori losses are estimated at 25[4].

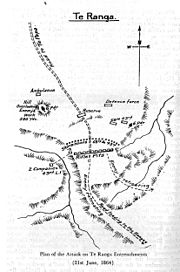

Te Ranga (21 June 1864)

One of the bloodiest battles in the New Zealand Wars occurred at Te Ranga, when 600 European soldiers surprised a garrison of Maori beginning to prepare new fortifications. Further British reinforcements were sent for, and when they arrived, a general advance was ordered. Fierce hand-to-hand fighting occurred, and at the end of the day '108 Maories were buried in the rifle pits which they themselves dug the morning before' (Cameron) [5]

Fortifications

Alexandra Redoubt Pirongia (Established 1872)

Firth Tower (Built 1882)

<kaltura-widget kalturaid='18g6pawld3' size='M' align='R'/>'The Firth Tower was built in 1882 by Josiah Clifton Firth, to provide a lookout over the country side and it was used as the estate office and as sleeping quarters for single men.'[6] Firth was a prominent land baron/speculator, who in 1866 had control of 55,000 acres of the Matamata plains. He was in favour of the Waikato invasion as he saw European control of the fertile Waikato plains as being essential to the colony's growth.[7]

- Jump up ↑ P.134, Belich, The New Zealand Wars

- Jump up ↑ P.365-66, Cowan, The New Zealand Wars, Vol I

- Jump up ↑ P.90, Prickett, Landscapes of Conflict

- Jump up ↑ P.90, Prickett, Landscapes of Conflict

- Jump up ↑ P.94, Prickett, Landscapes of Conflict.

- Jump up ↑ http://www.firthtower.co.nz/home

- Jump up ↑ http://www.dnzb.govt.nz/DNZB/alt_essayBody.asp?essayID=1F7