Cultural Anthropology/Social Institutions/Marriage

Contents

Key Terms & Concepts

- Marriage

- Types of marriage: monogamy, polygamy, polygyny, polyandry, group, symbolic, levirate, sororate, ghost marriage, fixed-term, fictive

- Serial monogamy

- Fraternal polyandry

- Incest

- Exogamy

- Endogamy

- Bride wealth

- Bride price

- Bride service

- Dowry

- Hypergamy

- Indirect dowry

- Woman exchange

- Gift exchange

Marriage

All societies have customs governing how and under what circumstances sex and reproduction can occur--generally marriage plays a central role in these customs.

Marriage is a socially approved union that united two or more individuals as spouses. Implicit in this union is that there will be sexual relations, reproduction, and permanence in the relationship.

Functions of Marriage

1. Marriage regulates sexual behavior.Marriage helps cultural groups to have a measure of control over population growth by providing proscribed rules about when it is appropriate to have children. Regulating sexual behavior helps to reduce sexual competition and negative effects associated with sexual competition. This does not mean that there are no socially approved sexual unions that take place outside of marriage. Early anthropological studies documented that the Toda living in the Nilgiri Mountains of Southern India allowed married women to have intercourse with male priests with the husband's approval. In the Philippines, the Kalinda institutionalized mistresses. If a man's wife was unable to have children, he could take a mistress to have children. Usually his wife would help him choose a mistress.

2. Marriage fulfills the economic needs of marriage partners.

Marriage provides the framework within which people's needs are met: shelter, food, clothing, safety, etc. Through the institution of marriage, people know for whom they are economically and socially responsible.

3. Marriage perpetuates kinship groups.

This is related to the previous function, but instead of simply knowing who is with whom economically and socially, marriage, in a legitimate sense, lets people know about inheritance.

4. Marriage provides an institution for the care and enculturation of children.

Within the umbrella of the marriage, children begin to learn their gender roles and other cultural norms. Marriage lets everyone know who is responsible for children. It legitimizes children by socially establishing their birthrights.

Forms of marriage

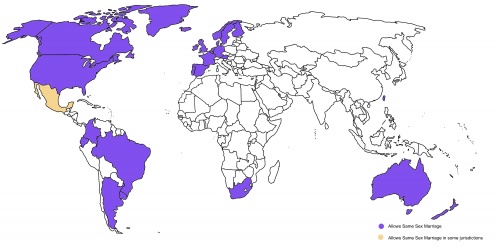

Monogamy, the union between two individuals, is the most common form of marriage. While monogamy traditionally referred to the union of one man and one woman, there are some countries that recognize same-sex unions. As of October 2019, thirty countries legally allow same-sex marriage and one, Mexico, allows it in some states. In other countries, the debate continues over whether or not to legalize same-sex marriage or guarantee rights to homosexuals. For instance, certain states in the United States and Mexico allow same-sex marriage, but not the entire nation. Serial monogamy, where an individual has multiple spouses over their lifetime, but only one at a time, is quite common in industrial societies.

Polygamy, the union between three or more individuals, is the second most common form of marriage. Generally, when polygamy is mentioned by the media, a marriage between a man and multiple women is being referenced; however, the term is being misused. Polygyny is the correct term for a marriage between a man and multiple women. Polyandry refers to a marriage between a woman and multiple men. Polyandry mostly occurs between a woman and brothers, a system referred to as fraternal polyandry. One reason that polyandry might be the preferred marriage pattern for a group is if there is a shortage of women or land is scarce. For instance, the Nyinba of Nepal practice fraternal polyandry because there is not enough land to divide between brothers and the high mortality rate of female child and infant mortality. Male children are preferred, therefore, are better cared for than female offspring (Bonvillain 2010: 218-219).

Polygyny is more common than polyandry. It is generally found in societies where rapid population growth is beneficial to the survival of the group, such as frontier and warrior societies, or where the ratio of women to men is high. Men with multiple wives and many children usually have higher status within the group because they have demonstrated that they can afford to support a large family. A man may also marry several women to help increase his wealth as he will then have more hands helping to bring in resources to the family. Many groups across the globe have or do practice polygyny, e.g., G/wi, Turkana, Samburu, and the Tswana.

A question that anthropologists asked was, what are the benefits of multiple spouses? What they found were several possible benefits:

- increased social status

- a new set of affines (in-laws) gives individuals more people for help w/trade, political alliances, support

- a larger labor force

- lessens the burden of work because it distributed among several women

- better chance children are provided for

Group marriage is a rare form of marriage where several males are married simultaneously to several females. This form of marriage was once practiced by the Toda; however, it is no longer known in any extant society.

There are a few other types of marriage. A symbolic marriage is one that does not establish economic or social ties, e.g., a Catholic nun marrying Jesus Christ. Fixed-term marriages are temporary marriages that are entered into for a fixed period of time. Once the time period is ended, the parties go their separate ways. There may be a financial gain for the woman, however, there are no social ties once the marriage has ended. Fixed-term marriages legitimize sexual relationships for individuals whose culture may forbid sexual relationships outside of marriage, e.g., soldiers during times of war or students attending college in a foreign country.

Some cultures have developed special rules for marriage if a married family member dies. The levirate obliges a man to marry his deceased brother's wife; e.g., Orthodox Judaism (although rarely practiced today, the widow must perform the chalitzah ceremony before she can remarry). The brother is then responsible for his brother's widow and children. This helps keep the children and other resources the deceased had collected within the family. The sororate is the flip side of the levirate. In this system, a woman must marry the husband of her deceased sister. The Amahuaca, who live in South America along the Inuya and Sapahua Rivers in Peru and Brazil, practice both the levirate and the sororate. The Nuer practice a form of the levirate called ghost marriage. If an elder brother dies without fathering children, one of his younger brothers must marry his widow. Children resulting from the ghost marriage are considered the offspring of the deceased brother (Bonvillain 2010).

Rules for Marriage

For the societies that practice marriage there are rules about whom one can marry and cannot marry (note: not all groups marry; traditionally the Na in Southwest China do not marry). All societies have some form of an incest taboo that forbids sexual relationships with certain people. This is variable from culture to culture. Several explanations have been proferred to explain the origins of incest taboos. One cites biological reasons. Non-human primates seem to have an instinctual aversion to having sex with near relatives, so perhaps the same happens for humans. Another biological reason is that the incest taboo was established to maintain biological diversity. This suggests that people understood the consequences of breeding with relatives.

Another theory suggests that familiarity breeds contempt, while yet another suggests that incest taboos were developed to ensure that alliances were made outside of the family. Whatever the case may be, there have been culturally approved violations of the incest taboo usually in royal families such as those in pre-contact Hawaii, and Ancient Egypt (Bonvillain 2010).

Exogamy stipulates that an individual must marry outside of a kin, residential, or other specified group. For instance, the Yanomami must marry outside of their residential village. Endogamy, on the other hand, stipulates that an individual must marry within a specified kinship categories or social group. The classic example of endogamy is the Indian caste system. Arranged marriages are quite common among human societies. With arranged marriages, family elders, usually the parents, choose spouses for their children. Arranged marriages promote political, social, and economic ties.

Sometimes within the practices outlined above, other rules that single out certain kin as ideal marriage partners are adhered to. Cross-cousin marriage unites cousins linked by parents of opposite sex (brother/sister) while parallel-cousin marriage unites the children of siblings of the same sex. The benefit of these types of marriages is that it helps to maintain the family lineage and resources.

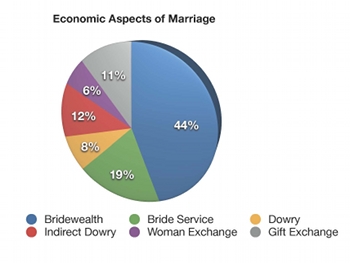

Economic Aspects of Marriage

Most marriages have some type of economic exchange associated with them. Only about 25% of marriages do not have an economic aspect (Ember and Ember 2011: 195).Anthropologists have identified the following practices:

Bridewealth or Bride price: In this practice goods are transferred from the groom's family to bride's family in compensation for losing the productive and reproductive services of one of their daughters.

Bride service: This entails the groom performing a service for the family of the bride. Bride service could take several months or even years to complete.

Dowry: Dowry generally is practiced in cultures where women's roles are less valued then men. This practice requires the transfer of goods from the bride's family to the groom to compensate for acceptance of the responsibility of her support. This is most common in pastoral or agricultural societies where a market exchange is prevalent. Hypergamy occurs when a woman uses her dowry to "marry up" and increase her and subsequently her children's social status. Indirect dowry is a little like bride price. With this custom, the groom's family gives goods to the bride's father who in turn gifts them to his daughter.

Woman exchange: With woman exchange, no gifts are exchanged by the families, but each family gives a bride to the other family; each family loses a daughter but gains a daughter-in-law.

Gift exchange: In this practice, the families of the betrothed exchange gifts of equal value.

References

Bonvillain, Nancy. 2010. Cultural Anthropology, 2nd edition. Boston: Pearson Education, Inc.

Crapo, Richley. 2002. Cultural Anthropology: Understanding Ourselves and Others. Boston: McGraw Hill Higher Education.

Dole, Gertrude Evelyn. 2020. “Culture Summary: Amahuaca.” New Haven: Human Relations Area Files. https://ehrafworldcultures-yale-edu.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/document?id=se06-000.

Ember, Carol R. and Melvin Ember. 2011. Cultural Anthropology, 13th edition. Boston: Pearson Education, Inc.

Freedom to Marry. n.d. The Freedom to Marry Internationally. http://www.freedomtomarry.org/landscape/entry/c/international, accessed February 19, 2015.

Harris, Marvin and Oran Johnson. 2007. Cultural Anthropology, 7th edition. Boston: Pearson Education, Inc.

Keen, Ian. 2006. Polygyny. In Encyclopedia of Anthropology, Vol. 4, H. James Birx, ed. Thousand Oak, CA: Sage Reference, p. 1882-1884.

Lavenda Robert H. and Emily A. Schultz. 2010. Core Concepts in Cultural Anthropology, 4th edition. Boston: McGraw Hill Higher Education.

Velioti-Georgopoulos, Maria. 2006. Marriage. In Encyclopedia of Anthropology, Vol. 4, H. James Birx, ed. Thousand Oak, CA: Sage Reference, p. 1536-1540.

Walker, Anthrony R. 1996. Toda. In Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Vol. 3, South Asia. New York: Macmillan Refernce USA, p. 294-298.