Biological Anthropology/Unit 1: Evolutionary Theory/Darwinian Evolution

Contents

- 1 IMPORTANT NOTE: THESE PAGES WILL NO LONGER BE UPDATED. THEY HAVE BEEN MOVED TO PRESSBOOKS AS PART OF A COLLEGE INITIATIVE TO COLLECT OER MATERIALS IN ONE PLACE FOR STUDENTS.

- 2 Who was Charles Darwin?

- 3 Darwin: The Early Years

- 4 The Beagle Voyage

- 5 The Theory of Descent with Modification through Natural Selection

- 6 References

IMPORTANT NOTE: THESE PAGES WILL NO LONGER BE UPDATED. THEY HAVE BEEN MOVED TO PRESSBOOKS AS PART OF A COLLEGE INITIATIVE TO COLLECT OER MATERIALS IN ONE PLACE FOR STUDENTS.

Note: Links are provided to various subjects for students who want to explore further.

Who was Charles Darwin?

Ernst Mayr claims, and many would agree, that Charles Darwin has done more to influence the philosophy of science, evolutionary biology, and the modern zeitgeist than any other individual (Mayr 2000: 78). Darwin developed a comprehensive biological theory of evolution that provided a unity to the natural world never before seen. He demonstrated the importance of historicity in science as well as a methodology that involved observation, comparison and classification, not just experimentation. Darwin's ideas, which rocked the foundation of Western society, still create heated debate in the modern world (Mayr 2000).

So, just who was Charles Darwin? Optional: For a quick introduction to Darwin, watch the PBS video "Who was Charles Darwin?"

Darwin: The Early Years

Darwin was born on February 12, 1809 in Shrewsbury, England. His father, Robert, and grandfather, Erasmus, were both physicians. His mother, Susannah, was a part of the Wedgwood family, famous even today for their fine china. Erasmus Darwin is remembered for his work Zoonomia, which attempts to explain the natural world using evolutionary principles (Mayr 2000). It is clear that Darwin was introduced to current intellectual thought about evolution when he was young (Darwin 1887).

Darwin grew up with a love of the natural world. Darwin himself tells us that early on he developed a love of travel and collecting things, including minerals and insects:

With respect to science, I continued collecting minerals with much zeal, but quite unscientifically—all that I cared about was a new-named mineral, and I hardly attempted to classify them. I must have observed insects with some little care, for when ten years old (1819) I went for three weeks to Plas Edwards on the sea-coast in Wales, I was very much interested and surprised at seeing a large black and scarlet Hemipterous insect, many moths (Zygæna), and a Cicindela which are not found in Shropshire. I almost made up my mind to begin collecting all the insects which I could find dead, for on consulting my sister I concluded that it was not right to kill insects for the sake of making a collection. From reading White's 'Selborne,' I took much pleasure in watching the habits of birds, and even made notes on the subject. In my simplicity I remember wondering why every gentleman did not become an ornithologist (Darwin 1887: 34-35).

Darwin carried this love of the natural world to the University of Edinburgh, where he was introduced to the work of Cuvier, Lamarck, and Saint-Hilaire (Young 2007), and subsequently, the University of Cambridge. At Edinburgh, Darwin studied medicine, but when it became apparent that the young Darwin had no interest in medicine, his father sent him to study theology at Cambridge. It was at Cambridge that Darwin's love of natural history flourished. He studied and worked with noted botanist J. S. Henslow, who would be instrumental in getting Darwin on the H.M.S. Beagle, scientific generalist, William Whewell, and geologist, Adam Sedgwick, all of whom were influential in his intellectual development, although Henslow would be the most critical individual in Darwin's post-college life (Bowler 1992, Mayr 1991, Young 2007). While at Cambridge, Darwin became an avid collector of beetles. This activity helped him become familiar with comparative anatomy,

The pretty Panagaus crux-major was a treasure in those days, and here at Down I saw a beetle running across a walk, and on picking it up instantly perceived that it differed slightly from P. crux-major, and it turned out to be P. quadripunctatus, which is only a variety or closely allied species, differing from it very slightly in outline (Darwin 1887:51),

a methodology that would be critical to the development of his evolutionary theory.

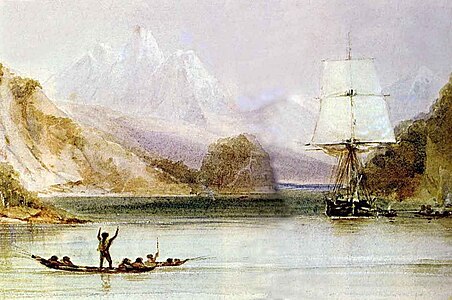

After graduating from Cambridge, Henslow helped Darwin secure a position aboard the H.M.S. Beagle as the ship's naturalist. He almost did not make the trip as his father was against it, but his uncle, Josiah Wedgwood, convinced Darwin's father to let him go on the voyage (Eldredge 2005). The Beagle, under the captaincy of Robert Fitzroy, left England on December 27, 1831 with the goal of charting the waters of South America (Bowler 1992, Futuyma 1986). While on the Beagle, Darwin, who was still an orthodox member of the Church of England (Futuyma 1986), made numerous observations that would eventually lead him to develop his theory of evolution by natural selection.

The Beagle Voyage

Optional: To read some of Darwin's journal entries for the voyage, check out The Beagle Voyage or for a complete collection, see Journal of Researches

During the five years Darwin was on board the Beagle, he read such scientific works as Charles Lyell's Principles of Geology and made observations that eventually led him to question his belief in the fixity of species, a commonly held notion that species were unchanging and perfect in their environment. He collected fossils, rocks, plants and animals, many of which were shipped back to England where eventually specialists such as the ornithologist John Gould examined the specimens. Darwin's discovery of a new species of the rhea living in the same area as the already known rhea raised questions about perfect adaptation...if it were true, why would there be two species of rhea in the same area [1]? However, it was the Beagle's stop in the Galápagos Islands that would be most important for the later development of his theory.

In the Galapagos, Darwin studied birds, iguanas and tortoises. The natives of the Galápagos showed Darwin how to determine which island the tortoises came from based on the shape of their shells. After learning this, he returned to the birds he had collected while in the Galápagos and sorted them by island. This gave Darwin, "...an unrivalled [sic] opportunity to study the effects of geographical isolation in the production of new species" (Bowler 1992: 300). It would be the Galápagos birds, specifically the mockingbirds, that would lead Darwin to his ideas about natural selection (learn more about the mockingbirds).

Optional: You can read more about the Beagle voyage by visiting the American Natural History Museum's Darwin Exhibition.

After the Beagle

Upon his return to England in October 1836, Darwin plunged himself into the scientific community of London. He had worked hard while on the Beagle so that he would not have to become a clergyman.

As far as I can judge of myself, I worked to the utmost during the voyage from the mere pleasure of investigation, and from my strong desire to add a few facts to the great mass of facts in Natural Science. But I was also ambitious to take a fair place among scientific men--whether more ambitious or less so than most of my fellow-workers, I can form no opinion (Charles Darwin quoted in Eldredge 2005: 27).

Henslow and Lyell had made Darwin well known in scientific circles while he was still at sea, so he readily became active in the Geological Society (Bowler 1992, Eldredge 2005) and the Athenaeum Club, a gentlemen's club that served as a meeting place for those of an intellectual bent (Eldredge 2005).

One of the first things Darwin did on his return was to organize and ship his collections to various specialists. Ornithologist John Gould quickly examined Darwin's collection of birds, informing him that the mockingbirds in the collection were in fact different species of mockingbirds, some from the various Galápagos Islands and some from the South American mainland. Darwin theorized that this could only be explained if the island birds' antecedents had found their way from the mainland to the islands. Once there, the descendents were gradually modified until they became new species (Young 2007: 108). Here we find Darwin's coherent thoughts on the role geographic isolation has in speciation, or the creation of new species. By March 1837, Darwin had rejected the idea of the fixity of species and creation by design and accepted the idea of evolution and the role of geographic isolation in speciation (Futuyma 1986, Mayr 1991).

In July 1837, Darwin opened his first notebook, 'Transmutation of Species,' which during this time in history was code for evolution. In this notebook, Darwin explored ideas about reproduction and variation and the nature of species. By the time he concluded this notebook, Darwin has laid out his ideas on common descent and branching evolution. What he still didn't know at this point was how it all occured (Young 2007).

A year later, Darwin began his studies of artificial selection. His second notebook outlines his thoughts on variation and inheritance and their relation to adaptation (Young 2007). Darwin's studies of artificial selection helped him understand how a natural mechanism might work (Bowler 1992). Breeders at the time talked about something akin to natural selection but only in the context of how it kept species and varieties "true to type" (Young 2007: 112). When Darwin read Thomas Malthus's work, An Essay on the Principle of Population, in 1838, the concepts Malthus outlined on exponential population growth and competition among members of a population for a limited food supply provided the crucial piece that was missing. Darwin realized that in light of competition among members of a population, variations of traits that allowed one member to have an advantage over other member would be preserved. He further concluded that disadvantageous variations would die out (Young 2007). Darwin now understood how it all occurred for all of nature, including humans.

As soon as I had become, in the year 1837 or 1838, convinced that species are mutable productions, I could not avoid the belief that man must come from under the same law (Darwin quoted in Eldredge 2005: 29.).

Darwin married his cousin, Emma Wedgwood, in 1839. By 1842, the Darwins moved from London to Downe in Kent in order for their children to grow up in the country and also for Darwin's health. In his later years, Darwin was plagued with ill health. While we do not know exactly from what he suffered, the symptoms suggest a malfunctioning of the autonomous nervous system (Mayr 1991).

In 1842, Darwin outlined his ideas on evolution by natural selection, expanding further in an 1844 essay that was to published only upon the event of his premature death. Bowler (1992) suggests Darwin did not publish at this time for two reasons: 1) the social climate--there was quite a bit of debate over Lamarck's theory of evolution and Robert Chambers' Vestiges that discussed evolution as part of a divine plan, and 2) he could not explain why the fossil record showed "...that many families had been subject to a constant trend towards increasing levels of specialization" (Bowler 1992: 304). The answer to this question would come a decade later when Darwin figured out that specialization provided an advantage even if the environment was stable because it cut down on competition for resources (Bowler 1992). During his time at Downe, Darwin used the hypothetico-deductive method (more commonly known as the scientific method) to build his case for evolution by natural selection, particularly in his work with pigeons (Young 2007).

Darwin began to write his "Big Species" book in 1856. He first published his ideas in 1858 after receiving a manuscript from Alfred Russel Wallace that outlined his ideas on natural selection, which coincided with Darwin's. At the urging of close friends in the scientific community, Darwin quickly put together a paper based on his 1844 essay that was presented by Charles Lyell and Joseph Hooker at the Linnean Society on July 1, 1858 along with Wallace's manuscript. Darwin then set to work on putting together an abstract of his Big Species book, which was published in 1859. This abstract, On the Origin of Species by Natural Selection, sold out in one day (Futuyma 1986, Mayr 1991, Young 2007). It was "the book that shook the world" (Mayr 1991: 7).

After the publication of Origin, Darwin's work focused on expanding on ideas that were touched on in the abstract, but not completely described. His other contributions to biology include The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication (1868), The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871), The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), Insectivorous Plants (1875), The Effects of Cross- and Fertilization in the Vegetable Kingdom (1876), The Different Forms of Flowers on Plants of the Same Species (1877), The Power of Movement in Plants (1880 with Sir Francis Darwin), and The Formation of Vegetable Mold, through the Action of Worms, with Observations on Their Habits (1881).

Darwin died in 1882, but his work continued to be reviewed and oftentimes vilified by philosophers, theologians, scientists. etc. Darwin had a number of friends that supported his work both before and after his death, and while most scientists of the time came to support Darwin's proposal about common descent, few adhered to his concept of natural selection (Mayr 1991). It would not be until the 1920s when a fundamental change occurred in the thinking about organisms that the true genius of Darwin's work would be recognized on a broader scale (Futuyma 1986).

Darwin's contribution is summed up nicely by Futuyma (1986:6):

Darwin was the first to marshall on so grand a scale the evidence of the first thesis [i.e., descent with modification from a common ancestor], the historical reality of evolution by drawing on all relevant sources of information: the fossil record, the geographic distribution of species, comparative anatomy and embryology, and the modification of domesticated organisms.

Mayr (1992) states that Darwin was unique among scientists of his day because he was not only a great naturalist and biologist, but was a great theoretician and experimenter. It was these differences that allowed him to make links across fields and develop his comprehensive, complex theor(ies) of evolution.

The Theory of Descent with Modification through Natural Selection

All information in this subsection is drawn from Mayr 1991.

Darwin's theory is actually a series of five theories:

- Evolution as such: species are not immutable; they change slowly and steadily over time. This idea challenged the commonly held belief that there was a perfect design to life on earth.

- Common descent: groups of organisms come from a common ancestor and all organisms ultimately originate from a single origin of life on earth. This idea provided a unity to biological life that had never been seen before.

- Multiplication of species: geographic isolation lead to the evolution of new species. This idea explained the natural biological diversity on earth.

- Gradualism: change occurs over long periods of time. This idea was in opposition to the contention that new species arose suddenly (saltation).

- Natural selection: those individuals with variations (traits) best suited to enable an individual to reproduce within an environment are more likely to pass on their traits to next generation. Each generation would produce more variation, when again, the traits best suited to enable survival would be passed on. The classic example of natural selection in action is the peppered moth. Learn more about this moth by watching a short video on YouTube or read this short article.

But there were some things that Darwin didn't know, namely, how traits were inherited or what caused variation within a population. Darwin also could not account for how similar species got on different continents, e.g., the ostrich in Africa and the rhea in South America. It would take decades for geologists to develop the theory of plate tectonics. Geologists in Darwin's day did not estimate the earth over 100 million years old, not enough time for evolution to work, but none of these things take away from the brilliancy or resiliency of Darwin's work. Over 100 years of testing has refined Darwin's theory while at the same time demonstrating over and over that his basic ideas, particularly natural selection, hold true. For more on what Darwin didn't know when he published his theory, check out this article from the Smithsonian Magazine.

What was it about Darwin's theory that "shook the world"? Some of his ideas challenged religious dogma and others challenged secular philosophies. Religious dogma that was directly challenged was the belief in the constancy of the world. The predominant belief in Europe and the United States was that while there had been a few catastrophes, e.g., Noah's flood, the world remained unchanged from when it was created approximately 6000 years ago by a devine Creator. All organisms were created to perfectly adapted to their environment, therefore, they did not change. Man (and it was the common vernacular of the time), with his unique soul, was separate from the rest of nature. In the arena of secular philosophy, Darwin's ideas challenged essentialism, or the fixed properties of an entity, the "...causal processes of nature as they had been elaborated by the physicists" (Mayr 1991: 39), e.g., Newton, and teleology, or a pre-determined end. While science has tested and retested Darwin's ideas and subsequently developed a synthetic theory of evolution (the modern synthesis), the debate continues on in many religious circles. To read more about the modern debate between religion and evolution visit the Talk Origins "God and Evolution" page.

References

Bowler PJ. 1992. The Environmental Sciences. New York (NY): W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Darwin F, editor. 1887. The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin. London: John Murrary, Ablemarle Street.

Eldredge N. 2005. Darwin: Discoering the Tree of Life. New York (NY): W. W. Norton & Company.

Futuyma DJ. 1986. Evolutionary Biology, 2nd edition. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates, Inc.

Hayden T. 2009. What Charles Darwin Didn't Know. Smithsonian (February). http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/What-Darwin-Didnt-Know.html?c=y&page=1. Accessed. 2010 October 15.

Mayr E. 1991. One Long Argument: Charles Darwin and the Genesis of Modern Evolutionary Thought. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press.

Mayr E. 2000. Darwin's Influence on Modern Thought. Sci Am 283 (1): 78-83.

Young D. 2007. The Discovery of Evolution, 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.