Tech-MODE in Uganda

Contents

- 1 Executive summary

- 2 Contents

- 3 Principal acronyms

- 4 1 Agriculture in Uganda’s economy

- 5 2 Agricultural training and education in Uganda

- 6 3 Agricultural education and training policies in Uganda

- 7 4 National ICT and distance education policies

- 8 5 Status of ICT and Tech-MODE for agricultural education and extension

- 9 6 Issues affecting introduction and adoption of Tech-MODE

- 10 7 Facilities and resources for implementation of Tech-MODE

- 11 8 Capacity strengthening needs to support Tech-MODE

- 12 9 Collaboration in Tech-MODE for agricultural education and training

- 13 10 Recommendations

- 14 11 References

- 15 Related information

- 16 Web Resources

Executive summary

Uganda is well-endowed with natural resources but remains a highly indebted poor country (HIPC) and one of the world’s twelve poorest countries characterized by prevalent hunger, malnutrition, low life expectancy (52 yrs), high infant mortality (67/1000) and death rates (13/1000). The economy is predominantly agrarian constituting 82% of the labour force. Poverty is largely attributed to the low human resource capacity in harnessing science and information communications technology (ICT) to overcome the constraints in agricultural production (e.g. drought, pests, diseases, weeds, markets, soil infertility). A study conducted by the International Food and Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) revealed that the greatest reductions in poverty and marginal returns in agricultural production in Uganda came from investments in agricultural research and extension followed by education.

The Inter Academy Council (2004) notes that the next generation of African students must have a strong and holistic science-based training with problem solving and critical thinking skills. In addition, they must possess good communication and inter-personal skills. This is a challenge for which the existing predominantly face-to-face mode of training in Uganda is compelled to face amidst the growing population. Implicitly, the future of agricultural education and research lies in exploiting advances in technology-mediated open and distance learning (Tech-MODE) because of its flexibility, reduced cost and interactive approach for reaching out to a larger population of learners.

This country report highlights the major ways in which agricultural education is imparted at various levels in Uganda. An attempt has also been made to explore the potential for the use of ICT in agricultural education and training in Uganda. The policy environment surrounding the use of ICT is discussed and the infrastructural, human and policy challenges facing Tech-MODE have been identified. Finally, a few recommendations have been made for strengthening agricultural education to enhance its contribution to livelihoods using Tech-MODE. It is envisaged that the information here will inform the process of nurturing a partnership between the Commonwealth of Learning (COL), the Forum for Agriculture Research in Africa (FARA) and strategic institutions involved in agricultural capacity building in Uganda.

Keywords: Tech-MODE, distance learning, agriculture, Uganda

Contents

Executive summary

Principal acronyms

1 Agriculture in Uganda’s economy

2 Agricultural training and education in Uganda

3 Agricultural education and training policies in Uganda

4 National ICT and distance education policies

5 Status of ICT and Tech-MODE for agricultural education and extension

6 Issues affecting introduction and adoption of Tech-MODE

6.1 Opportunities

6.2 Challenges

7 Facilities and resources for implementation of Tech-MODE

8 Capacity strengthening needs to support Tech-MODE

9 Collaboration in Tech-MODE for agricultural education and training

10 Recommendations

11 References

Related information

Principal acronyms

ASARECA Association for Strengthening Agricultural Research in Eastern and Central Africa CGIAR Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research COL Commonwealth of Learning EAC East African Community FARA Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa GDP Gross Domestic Product ICT Information and Communication Technology(ies) NAADS National Agricultural Advisory Services NARO National Agricultural Research Organization NARS National Agricultural Research Systems NEPAD New Partnership for Agricultural Development ODL Open and Distance Learning RAIN Regional Agricultural Information Network of ASARECA RUFORUM Regional Universities Forum Tech-MODE Technology-Mediated Open and Distance Education

1 Agriculture in Uganda’s economy

Since Uganda’s independence, agriculture has been contributing the highest share of the national economy with about 80% in the 1960s. In the years that followed, the agricultural sector experienced negative growth rates due to civil strife, economic mismanagement, the disintegration of public infrastructure and services, a lack of adequate private sector investment and the scarcity of foreign exchange for agricultural inputs. Critical changes occurred between 1986 and 1992 because of the government’s economic recovery program introduced in 1987 and structural adjustment policies. The notable changes include liberalisation of the marketing of agricultural produce, abolition of export taxes and removal of other market distortions, establishment of regulatory and promotional agencies for key export crops, dissemination of quality control and market information. During this time, the agricultural sector experienced a high annual growth rate of 6% from 1992 to 1996.

In recent years, the contribution of agriculture to national economy has declined gradually, being replaced by industrial and tourism sectors. Although the proportion of the population living below the absolute poverty line has declined from 56% in 1992/93 to 35% in 1997/98 and 31% in 2007, household incomes are still low and food security is not guaranteed and about 40% of the population is food insecure (MFPED, 2007). The major reasons for this situation include weak linkages between the research system and the farmer, inadequate extension services that reach only a few farmers, low rates of technology adoption-(> 30%), and only one third of total food production is marketed and 56% of total agricultural GDP is subsistence production for household consumption.

Nevertheless, agriculture is the most important sector of the economy, employing over 80% of the labour force, and contributing 38% of GDP (2006) and 90% of exports. The importance of agriculture for the national economy has been recognised and the Plan for the Modernization of Agriculture (PMA), intended to establish improved agricultural methods and the commercialization of farming, was introduced in 2000. Central to plans to modernise the agricultural sector is the design of a policy and, subsequently, a strategy to cover both the formal and non-formal provision of agricultural education and training. In 2003, a task force was established by the Ministry of Education and Sports (MOES), charged with the development of the policy and strategy.

2 Agricultural training and education in Uganda

The importance of agricultural training and education to the national economy of Uganda is recognised by the government as reflected in the curriculum of education in both the secondary and tertiary institutions. However, the relationship between agricultural training and education, and agricultural development in Uganda is a subject for research. About 67% of Uganda’s GDP is contributed by smallholder subsistence farmers engaged in agriculture and largely without formal education. Graduates in agriculture often view their education as the door to exit from the `poor’ farming echelons. Many smallholder farmers make huge sacrifices to support the training and education of their children while instilling in them the spirit of aspiration to be better than them. This begins early before or during primary schooling.

In primary schools, agricultural education is not formal but most traditional schools own farm gardens where pupils participate occasionally in farm activities. In many cases, participation in school gardening is used as a punishment. This is incongruous with the practice in more developed countries like South Africa, where school children actively and joyously do school gardening. Such cases serve as opportunities for exposure and change of mind sets using ICT. The primary targeting could be pupils but spreads to teachers and parents. Formal education starts at secondary level with agriculture as an optional subject.

In the past, there used to be a number of post-primary farm schools for those who were not able to continue to the secondary level (e.g. Ssese farm school) but most of them were converted into secondary schools. Secondary schools (lower and higher) are often ill-equipped for preparing students for careers in agriculture. In comparison with other subjects, there are very few books and training materials dedicated to agriculture. Besides, most of the teachers are often not originally trained in agriculture but adapted from other subjects such as biology.

At the tertiary level, there are two kinds of institutions for preparing professionals in agriculture, namely; agricultural colleges and Universities. The agricultural colleges are the equivalent of Community Colleges in the U.S. and they award diplomas and non-diploma certificates in agriculture. Until recently, we have had three agricultural colleges (Bukalasa, Busitema and Arapai). Busitema is gradually being transformed into a University. Graduates trained in colleges are highly skilled and often employed as farm managers, while those not placed serve in the decentralized local governments as extension workers. A few who excel and graduate with upper second or higher diploma classification often sit for a qualifying/mature entrance examination for entry into the university.

University-level agricultural education is probably the most popular for the higher secondary students, of sciences, and, for one reason or the other, fail to qualify for medicine. Often, those admitted do not place agricultural education as their first choice and hold a low interest. The solace comes from the diverse options including Agricultural Economics that guarantees departure from the “gas” in the labs and a “gap” with the soil. There are three public Universities (Makerere, Gulu and Kyambogo) and at least three private Universities that offer a bachelor’s degree in agriculture. Busitema University has been established by the Act of tertiary institutions and is in the process of admitting agriculture students at the bachelor’s level. Currently, only Makerere University offers postgraduate degrees in agriculture in Uganda. Plans are afoot at the Gulu University to begin Master’s degrees.

At Makerere University, agriculture related education is imparted at the Faculty of Agriculture and the School of Education. The School of Education, independent of the Faculty of Agriculture, educates teachers including those that teach agriculture in secondary schools and awards them a B.Sc. in Education. The Faculty of Agriculture trains agricultural professionals in the following programs:

- B.Sc. Agriculture

- B.Sc. Food Science and Technology

- B.Sc. Agricultural Extension Education

- B.Sc. Agricultural Engineering

- B.Sc. Agricultural Land use and Management

- B.Sc. Horticulture

- B. Agribusiness Management

In 2004, the Faculty of Agriculture in Makerere University started a Continuing Agricultural Education Centre (CAEC) located at the Makerere University Agricultural Research Institute, Kabanyolo (MUARIK) with the aim of providing in-service training in agricultural-related subjects for local government staff, private sector and individual farmers. Until recently, the training has largely followed the traditional face-to-face top down teaching with unidirectional flow of knowledge. In 2004, the University adopted the innovation systems perspective and trained an initial batch of 26 staff in personal mastery skills funded by the Rockefeller Foundation and IAR4D competences jointly conducted with the International Centre for Development Oriented Research in Agriculture (ICRA) and the National Agricultural Research Organization (NARO).

A survey conducted by the task force of the National Agricultural Education Strategy (NAES) in 2004 identified the following major challenges facing formal and non-formal agricultural training and education:

- Lack of a coherent policy for agricultural education and training.

- Insufficient funding for agricultural education and training.

- Ineffective institutional framework for the delivery of agricultural education and training.

- Inappropriate curricula and teaching and learning methodologies in agricultural education and training.

- Negative attitudes towards agriculture in general and agricultural education and training in particular.

These findings are in agreement with the Inter Academy Council (2004) which also noted that the graduates produced were lacking in a holistic system and critical thinking problem solving skills and were also ill-prepared to assist farmers in the real world. Clearly then, government commitment provides an environment conducive to promote agricultural education and training. As will be seen later in this case study, already some activities to this effect in the policies are being implemented.

3 Agricultural education and training policies in Uganda

For a long time, the government of Uganda has valued agricultural education and training but had not explicitly expressed its commitment to it. Recently, the government paid particular attention to agricultural training and education. However, efforts have been made to promote agricultural development and some of these developments are implemented through the following government interventions:

Plan for Modernization of Agriculture (PMA, 2000): The PMA is the country’s policy framework for promoting agricultural development largely by moving towards commercialisation. The Plan has the four main goals of:

- creating a framework for rapid economic growth and structural transformation;

- ensuring good governance and security;

- increasing the ability of the poor to raise incomes;

- increasing the quality of life of the poor.

The component of this policy framework responsible for non-formal training is the National Agricultural Advisory Services (NAADS). NAADS is a parastatal of the Government of Uganda designed to develop a demand-driven, client oriented and farmer-led agricultural private service delivery system particularly targeting the women and the poor. The NAADS programme was conceived as a result of the failure of traditional extension approaches to bring about desired productivity and expansion of agriculture, despite costly Government interventions (Master document of the NAADS Task Force and Joint Donor Groups, 2000).

Besides, there is a law, the National Agricultural Research Act, enacted by the Parliament in 2005 to ensure implementation of the National Agricultural Research Systems (NARS) policy, which considers all educational institutions as an integral part. Until recently, training for local farming communities was mainly through the public extension system with an extension officer located at the sub-county level to provide agricultural advice to farmers. Many Non-government Organisations (NGOs) and Community-Based Organizations (CBOs) still play a key role in agricultural extension and education using such approaches as the Farmers Field Schools (FFS) and the Training-and-Visit (T&V) extension.

In October 2003, the Ministry of Education and Sports produced the draft policy on agricultural education, the National Agricultural Education Strategy (Government of Uganda, 2003), which has the following specific objectives:

- Reform the institutional landscape to provide a coherent structure for efficient and effective delivery of formal and non-formal agricultural education and training nationally.

- Re-conceptualise the nature and form of both formal and non-formal agricultural education and training to ensure that the courses offered are relevant to the contemporary individual and societal needs.

- Ensure full participation of all the members of society regardless of gender or disability in formal and non-formal agricultural education and training.

- Raise awareness and improve the status of both the formal and non-formal agricultural education and training at all levels of the education system and in the society at large.

- Ensure adequate supply of well qualified teachers and instructors for formal and non-formal agricultural education and training.

- Establish linkages between providers of agricultural education and training with national research, experience and knowledge base.

- Define and implement an effective quality assurance system in the delivery of formal and non-formal agricultural education and training using both institutional and national mechanisms.

National Agricultural Education Policy (NAEP): The strategy in this policy is to reform learning and teaching practices to promote agriculture as a business and encourage people to join the agricultural sector. To ensure open participation, issues in the social environment, such as gender, conflicts and security, environment protection and HIV/AIDS will be addressed. An important strategy is capacity building and curriculum review to make agriculture relevant to local problems.

Education Sector Investment Plan: The Ministry of Education and Sports has developed the Education Sector Investment Plan, 2004-2015 and agriculture has been given special attention. A number of interventions related to agricultural education are being implemented by the Ministry of Education and Sports and these include the following:

- A revised primary school curriculum in which agricultural education is viewed as a discrete subject and examinable from 2005.

- Pre- and in-service teacher education programmes in some primary teachers’ colleges to improve teaching and learning methodologies.

- Promotion of a practical approach to agricultural education in core primary teachers’ colleges and their cluster schools.

- Training programs for specialist teachers of agricultural education to promote the use of locally available teaching and learning materials.

- Incremental provision of equipment and teaching and learning materials for agricultural education and training.

- Introduction of an holistic approach to educational development as recommended in the mid-term review of the Education Sector Investement Plan (ESIP).

- An extensive programme of functional adult literacy.

- Plans to establish 850 community-based polytechnics in which agricultural education and training will be a compulsory field of study.

- Creation of District Agricultural Training and Information Centres (DATICs)

- Introduction of a new approach to the agricultural extension provision through NAADS which seeks to empower farmers to demand services (agricultural education and training) according to their needs through a farmers’ forum.

- Decentralization of NARO’s services as part of its outreach and partnership initiative to take research, training, information exchange and technology dissemination near to farmers.

4 National ICT and distance education policies

There is no explicit policy specific to agriculture or to education in general, but there has been a series of policy changes to facilitate the increasing use of ICT in education and public administration. It is increasingly accepted that ICT is a change agent of the 20th century and has the potential to fundamentally transform education, governance, commerce and the ability of citizens to participate more in the development process. The sustainability of high education standards, economic growth and efficiency in operations of both private and public institutions, are dependent on the adoption and effective utilisation of ICT.

Although ICT may have developed earlier in many countries, Africa in general and sub-Saharan Africa in particular, still lags behind other regions in its use in training and education, research and administration. Over time, these technologies have gradually picked up and their use is getting widespread (Stephen and Shin, 2001). Training, research and education in agriculture is increasingly taking advantage of these developments to improve the quality and relevance of agriculture to national economies.

In Uganda, this trend is still emerging and has already taken shape in some institutions such as Makerere University, Uganda Martyr’s University and the Uganda Management Institute (UMI). The government has also recognized the importance of ICT and a policy is available to guide the activities. The government has even committed a whole ministry to oversee the implementation of the proposed activities in the National Information and Communication Technology Services and System Policy and Master Plan.

The current policy on ICT and regulatory environment in Uganda dates back to the telecommunications sector policy of 1996, which was operationalised by the Uganda Communications Act, 1997. The policy on ICT developed by the government in 2003 clearly recognises the relevance of ICT in

- health, education, agriculture, e-government, e-commerce;

- improved delivery of social services, reduction of vulnerability to natural disasters as well as reducing isolation of communities and providing immediate linkage to the modern world;

- improved transparency and governance through availability and use of ICT, introduction of new management and control methods in both public and private sectors facilitating enterprise resource management;

- introduction to the new knowledge-based economy;

- modernisation of the private sector through improved market access, sales, trade and knowledge of business trends;

- facilitation of research and development.

The current status of ICT in Uganda has been influenced by various policies, statutes, laws, acts and regulations. The more relevant ones include the following:

- The Press and Journalist Statute (1995) which extended Article 29(1) (Freedom of Expression) of the Constitution to the print media. It also created the Media Council, the National Institute of Journalists of Uganda and a Disciplinary Committee within the Media Council. The Council is responsible for regulating eligibility for media ownership and requires journalists to register with the National Institute of Journalists of Uganda.

- The Electronic Media Statute (1996) created a licensing system, under the Broadcasting Council, for radio and television stations, cinemas and videotape rental businesses. The purchase, use, and sale of television sets were also to be subject to licensing by the Council.

- The Communications Act (1997) whose major objective was increasing the penetration and level of telecommunication services in the country through private sector investment rather than government intervention.

- The Rural Communications Development Policy (2001) aimed to provide access to basic communication services within reasonable distance to all people in Uganda.

- National Information and Communications Technology Policy Framework (2002) was prepared to give way to the ICT policy. The aim was to stimulate more participation in the socio-economic-political and other developmental activities, which lead to improved standards of living for the majority of Ugandans and ultimately enhance sustainable national development.

- The Information and Communication Technology Services and Systems: Policy and Master Plan came out of the policy framework and was finalised in 2003. Currently, the government has established a Ministry of ICT, which has the mandate to implement the policy.

5 Status of ICT and Tech-MODE for agricultural education and extension

Most of the agricultural training in Uganda is still predominantly face-to-face with limited use of ICT. Distance learning existed in Makerere University as early as 1953 but the focus centred on in-service training. In 1992, other degree programmes were introduced, which were extended to include graduate and diploma level training. To date, there are a diploma programme, three undergraduate programmes and one postgraduate programme taken under the distance learning arrangement. The course content and instruction is by blended delivery of face-to-face instruction and multimedia (e.g., books, CD, DVD).

A recent development is the USAID-sponsored project “Strengthening Agricultural and Environmental Capacity through Distance Education (SAEC-DE), which involves collaboration between Makerere University, University of Nairobi, University of Florida and International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) piloting distance education at Masters level for staff in the NARS to access degrees in the north without leaving home institutions. This project uses blended Tech-MODE and multi-media delivered by courier.

The use of ICT in agricultural education and training is yet to be exploited although distance learning is used in various universities and technical colleges. The Faculty of Computing and Information Technology at Makerere University provides the best facilities in Uganda and is the regional referral centre for ICT training, and works closely with the Directorate of Information and Communication Technology Unit of the University. The thrust has increasingly been to transform courses offered face-to-face to e-courses at certificate, graduate and postgraduate levels using various course management platforms (e.g., KEWL, WebCT, ETUDE and Blackboard). However, the number of students who take these courses is overwhelmingly high compared to the number of computers available with a ratio of computers to students at about 1:40.

The institute has begun expanding its facilities to promote ICT training extensively. The University library has provided the students with Internet kiosks to access the Internet for at least 30 minutes after booking in the morning. This is a good starting point for improving the students’ access to the Internet. In addition, it has piloted short training classes beyond midnight to try and overcome these challenges. Efforts to streamline and have a single course management platform are constrained by the binding contracts.

In other public universities such as Mbarara and Gulu, there is access to the Internet but its use for teaching is limited. In Gulu University in particular, academic staff have a common room with only two computers and four Internet ports, where one who has a laptop can access the Internet. However, in the department of computer sciences there are several computers, but their use is restricted to teaching the computer classes. In Kyambogo and Mbarara Universities, the situation is not much different except that the number of offices with the Internet access is more.

Other colleges and technical institutes still have limited access to computers and the Internet with the access restricted to important administrative offices. Martyr's University of Nkozi offers a distance learning combining face-to-face and other multimedia (e.g., books, CDs). Sometimes, the school library has been provided with a few computers but the computer to student ratio is normally too low to allow effective use.

For farmer training and other extension services, the Nakaseke Telecentre is an example of the application and development of ICT to enhance extension services. The Nakaseke Telecentre is part of a chain of five donor supported (UNESCO/IDRC/ ITU) telecentre projects initiated in Benin, Mali, Mozambique and Tanzania (Prakash, 2000). The overall objective of the project is to stimulate rural development by facilitating access to information, learning resources and communication technologies by the Nakaseke and Kasangombe communities and support improved medical services through telemedicine. The Nakaseke Multi-Purpose Community Telecentre has introduced new information and communication technologies to this rural area. In three years, the Telecentre has catalysed a number of development activities in the region.

6 Issues affecting introduction and adoption of Tech-MODE

Considering the available infrastructure, current and upcoming policies on ICT locally and regionally, many opportunities are available to promote Tech-MODE as a method of instruction in agriculture. However, several challenges still exist that may hamper the success in the wider use of Tech-MODE for agricultural education for development. What may be the opportunities and challenges?

6.1 Opportunities

Action Aid has made efforts to empower 26 communities of poor people in Uganda suffering from HIV/AIDS to advance their development using ICT. They concluded that ICT by themselves are not enough to bring about a reduction in poverty. The need of the hour is to mainstream ICT in the development initiatives. According to the study carried out by the International Food and Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), investments in agricultural research and extension as well as generic education had the greatest impacts on poverty and agricultural productivity.

Institutions like Makerere University are at an advanced stage of implementing their ICT action plans. This changing climate creates ample opportunities for the other institutions to support and/or emulate their programmes to fit into a framework at the national level (EAC, Secretariat, 2005).

The ICT trade liberalisation policy in Uganda has proved to be successful and helped the proliferation of the ICT usage in the country. A similar trade strategy with harmonised policies may well be adopted by potential institutions.

Several successful projects at the national level have created an enthusiastic environment for ICT-led initiatives though constraints in funding have hindered their scaling up. A good example is that >1.5 million people possess mobile phones.

There is a moderate growth in the pool of trained ICT personnel in the government offices, including the Ministry of Agriculture, across the region. However there is a problem of retaining these personnel in these departments. Apparently, at least every department has some ICT personnel. This is important because lobbying for promotion of Tech-MODE can have widespread acceptance by the government.

Mobile teledensity is improving at an impressive rate and a wider spectrum of Internet service options is available to the citizens today. The service providers, such as MTN, and Uganda Telecom, and other private individuals, are keen to provide connectivity at a better speed and price in more remote locations than urban hubs.

The presence of a common language of instruction in all institutions, English, makes it advantageous in terms of local expertise and a tradition of higher education. If properly planned, this can be instrumental in promoting inter-university education in the East African region.

Uganda is well-oriented for the strategic strengthening of key organisations to produce necessary trained personnel in ICT at all levels. A sensitised environment for higher education exists with a number of reputed centres of learning. Networking between institutes nationally proved to be encouraging (e.g., school net Uganda and Uganda Connect with a keen interest in expanding it to the regional level with universities / institutes joining hands in sharing experience, faculties and a credit transfer system. Currently, there are over 20 universities (both public and private) in Uganda. Networking between them and offering courses in ODL can go a long way to alleviate the existing scramble for education resulting from a large number of students.

The National Council for Higher Education, a regulatory agency established by an Act of Parliament to accredit Universities and their academic programmes can play a key role. This can further be developed to cover the East African Community by linking up with the Africa Virtual University, the Kenyatta University and some of the state of the art initiatives in open and distance learning (ODL) like the World Bank’s Global Knowledge Gateway Centre at Dar es Salaam through collaborative arrangements with the Inter- University Council of East Africa and The East African Institute of Higher Education Studies and Development (EAIHESD) to serve a wider clientele in the East African Community (EAC) region.

Possibilities could be explored to extend this to the sub-Saharan Africa region (including the Africa University, Zimbabwe) through the Regional Universities Forum (RUFORUM) that links higher education among several Universities and the Regional Agricultural Information Network (RAIN) of the Association for Strengthening Agricultural Research in Eastern and Central Africa (ASARECA). Linkages can be achieved across Africa through FARA programmes (e.g., RAILS, BASIC, SCARDA, SSA-CP) and New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) with technical support from COL.

Decentralisation of power in the government to the grassroots levels is emerging as a distinct trend in Uganda and ICT is increasingly being seen as a tool for good governance. Networks of parliamentarians are being established to create a mass awareness among decision-makers and support enabling legislation for the growth of ICT-led development programmes and business environment. In this effort, the government is planning to procure laptops for the legislators at a subsidised price.

Legal reforms are underway that could provide a conducive legal framework for electronic transactions. There is awareness among an increasingly large number of people about the advantages of offering online services.. In fact, the government has established a full ministry to cater to ICT. This ministry is concerned with the implementation of the National ICT policy.

The National Planning authority is committed to operationalising the national ICT Policy and the various ICT Master Plans (e-government, e-commerce, e-health, e-education and e-information).

6.2 Challenges

Power supply is erratic and unstable in rural areas and it demands an added cost of providing alternative source of energy for ICT installations in rural areas. In Uganda, only 4.3% of the households with 2% in rural areas have electricity connections.

Computing facilities are still at the rudimentary stage compared to the large-scale operations required to establish and implement a well-functional distance learning programme. Email is still not used as a regular mode of communication and the overall use of computers is limited to basic application as a word processor. Most of the offices of academic staff are not networked and interconnected through LAN/WAN.

Internet connectivity, even where available, is not accessible to all the staff and this facility is mostly restricted to a few depending on their ICT related job responsibilities. Where available, the bandwidth is a major constraint particularly to real time communication and this has greatly impeded teleconferencing. In Gulu University, for example, only the library is equipped with about 10 computers and students can access the Internet. Even then, the computers are relatively old (Windows 98, 2000 operating systems).

According to a survey by Mega-Tech (Government of Uganda, 2002), combined Teledensity (mobile + fixed) is still low (< 3%). The digital divide is acute in the region with an average 80%-90% telephone/Internet subscribers concentrated in capital/major cities. </nowiki>

Connectivity and bandwidth is a major constraint. Outside the capital cities and a few major towns, there is little Internet penetration, making it a difficult task to deliver government services online in such locations and communities. The awareness about ICT and benefits thereof is low and ICT training cost in such areas is prohibitive. In addition, the cost of bandwidth availability is poor and expensive.

Though partner states have initiated a number of websites for its ministries and parastatals, most of these are not interactive and provide static content. Local contents on the web are scarce and difficult to develop, let alone update.

Different legal provisions regarding electronic governance in general (e.g., Right to Information/Official Secrecy Laws) are still to be harmonised in order to exchange information among the partner institutions. With the emerging regional cooperation in EAC, as reflected in the recently launched Customs Union protocol, an appropriate measure in harmonising information management laws has become necessary.

7 Facilities and resources for implementation of Tech-MODE

Most of the institutions do not have the necessary infrastructure to provide all the desired services electronically to all the students. In all cases, higher bandwidth is a constraint due to lack of funds. Additionally, the power supply is erratic and hardly reaches far away rural areas, making it difficult. Computers are mostly standalone in offices and are not networked. However, some institutions and departments with necessary enthusiasm and access to funds have gone well ahead in networking and providing the intra-office electronic communication.

In most institutions that have the Internet, access is limited to a few individual officers and it is not preferred as a regular mode of communication with most of the official communication still being done in the conventional paper-based system. In fact, some people point out the lack of necessary legal framework (e.g. suitable amendments in the evidence Act) as a hindrance to large-scale use of e-mail as a valid mode of official communication. Another common problem among institutions relates to the space available for the establishment of computer facilities.

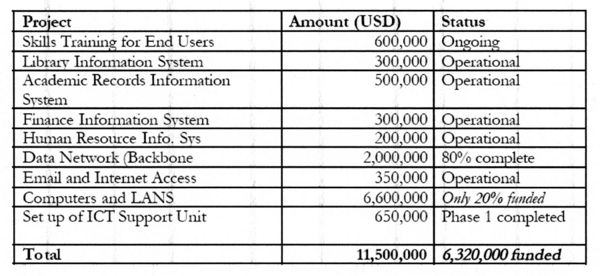

Makerere University has made substantive establishments in terms of infrastructure for ICT as can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1. ICT infrastructure in Makerere University

8 Capacity strengthening needs to support Tech-MODE

Although there are a number of universities and higher technical institutions in the country, there is an overall lack of awareness about ICT among the average student population and many of them do not know how to fit themselves into the new knowledge society. This scenario is acute because most of the staff in the institutions completed their education years ago and now suffer from a fear-psychosis in the fast changing automated office-environment. Therefore, the lack of necessary supporting staff to sustain the initiatives is a major weakness of the existing situation to launch a full-fledged Tech-MODE programme. Opportunities for ICT-related vocational and higher technical training is severely restricted and it is difficult for an average academic staff to update their ICT skills even though most of them have had some kind of basic training in the use of computers (Kwemara and Mayende, 2006).

The budgetary allocation for staff training in ICT is small in comparison to the size of the staff population and the growing need for trained staff to run the Tech-Mode programs efficiently and effectively. Since 2002, the e-Learning department of the Directorate for ICT support (DICTS) at Makerere University has trained over 3,000 university staff and is still conducting an e-learning and Knowledge Environment for Web-based Learning (KEWL) aimed at training Lecturers from different faculties/departments. Platforms such as KEWL provide for interactivity between lecturers and students. They also make learning a two-way process and an interesting practice. Given the establishments and the continuous training of workforce in the university, there is much hope that the future for Tech-MODE in Makerere University seems bright.

9 Collaboration in Tech-MODE for agricultural education and training

Linkages between internal and external institutions are still meagre. As mentioned earlier, the Department of Distance Education in Makerere University offers distance learning but it is important to note that the use of ICT is limited. It is only Uganda Martyr’s University that offers the Bachelor of Agriculture degree through the distance mode. Some linkages do exist among institutions. A diploma course is being offered jointly between the Open University of Tanzania and the Department of Distance Education of Makerere University.

A proposed training programme, Alliance for Improvement of Food Security for All (AINFSA), by the Department of Food Science and technology of Makerere University failed to start off after donor-funding failed to materialize. There is still a joint effort between Makerere University and the University of Wisconsin, Madison to develop a diploma programme in Integrated Food and Nutrition. The course is envisaged to adopt both traditional and modern methodology including correspondence, educational television, multimedia systems and Internet-based systems to ensure cost-effective tapping of top expertise at Makerere University and elsewhere.

The East African Community is another gateway to promote Tech-MODE across member states. Academic institutions should drive towards making policies to introduce ODL programmes at schools and higher education levels offering affordable access to the Internet and multimedia resources. This can be achieved by creating pools at identified centres of excellence in the region. The RUFORUM is a good entry point for such an initiative. These policies should clearly build a knowledge-sharing and collaborative agreement among leading institutions in the region with recognized expertise in the areas of public administration, management, scientific and agricultural research aimed at building a capital of trained human resources for efficiently running e-learning initiatives. A pilot programme in this direction will be undertaken with the existing higher/technical education institutions of partner states drawing up a plan to harmonise standards, curricula and credit transfer options for the region.

The EAC regional e-learning programme on public administration will include a systemic support to the regional cooperation in research and development, exchange of good practices and pedagogical resources, teacher training and development of e-learning content and services. An initial endeavour might be the scaling up of and broadening the coverage of the World Bank’s Global Knowledge Gateway based in Dar es Salaam across the partner states (EAC Secretariat, 2005).

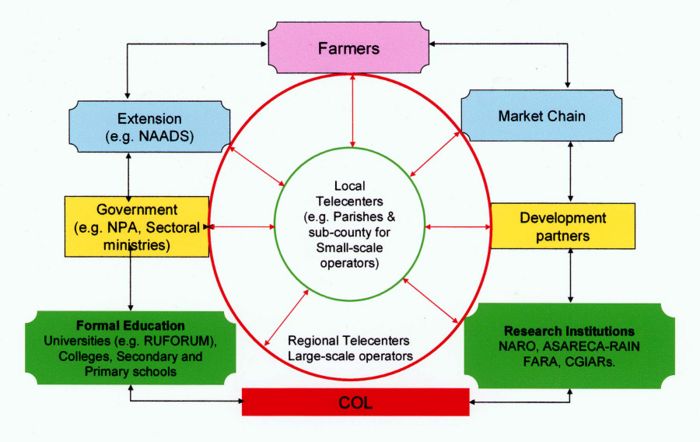

So far, the links are more evident at higher levels but there is a need to ramify similar linkages at the lower levels, for example, those between Agricultural Research and Development Centres (ARDS), and NAADS. This can be effected through web-aided interfaces to help farmers access recent information about the technological innovations in different parts of the country to bypass the high costs involved in conventional extension methods. A proposed model illustrated in Figure 1 is based on the linkages which can be developed:

Figure 1. Web-aided stakeholders interfaces for improved education training and education

It is important to acknowledge the scarcity of resources for building the entire complex system. Therefore, beginning with a few regional telecentres and expanding at a later period would be acceptable. The following are priority areas for consideration:

- develop a common framework for online learning and distance education among training institutions;

- strengthen mechanisms for communication and coordination of the training community;

- position institutional capacity-building within the external environment (e.g. university partners, educational networks and other learning institutions);

- establish common quality assurance standards for capacity-building, including monitoring and evaluation.

10 Recommendations

Consider the following recommendations:

- Lobby NEPAD for extension of fibre optics marine cable to East Africa.

- Jointly developing courses and learning materials (reusable learning objects) among universities and other higher institutions of learning is a starting point for distance learning.

- Support all universities, technical higher education institutions and at least a few major secondary schools to access the Internet for educational and research purposes preferably over a broadband connection. The secondary-level training in elementary computer techniques is necessary as an induction approach to the e-learning environment.

- Leverage strategic partnerships for DE and online learning to scale up research outputs for increased impacts

- COL to assist in enhancing the effectiveness and efficiency of the African Virtual University to national Universities and other institutions of learning.

- Strengthen the community of practice (training officers) to improve synergies and communication with partners. A broad-based e-leaning programme should launch a regional human resources development programme with appropriate structural funds and technical assistance from already established institutions within or from abroad, to provide ICT skills training. This initiative may be based on the proposed virtual university for the EAC.

- Capture synergies to enhance agricultural science and practice by strategically aligning Universities, development partners and relevant CGIAR centres and their resources.

- Support capacity building to establish a stable human resource base for propelling ODL in schools and Universities.

- Develop and deliver of modules aligned to the innovations systems through distance learning.

- Work with NAADS and linking with other institutions that work with farmers to improve service delivery by adopting the use of telecentres established at the sub-county level. Institutional participation is possible through specific tasks in the development of teaching materials for farmers and students. There is already a partnership between NARO and Makerere University where NARO staff have provision to teach in the University. This helps in developing and teaching materials that are suited to the local problems.

- Learning facilitators develop teaching materials for farmers and supply them to the telecentres where the extension officers facilitate farmers learning. Information may be developed in electronic media such as PowerPoint presentations, with illustrations and video recordings of field demonstrations.

- Link institutions involved in research through strengthening the efforts of the ASARECA network RAIN.

- Develop a robust framework of an action plan specifically drawn up by a joint committee of major tertiary level institutions and the National Planning Authority at the national level.

- Institutionalise a common quality assurance and standards system for training, education and learning in agriculture using Tech-MODE.

11 References

EAC Secretariat, 2005. Draft Regional e-Government Framework. Arusha, Tanzania JUNE 2005

EAC, 2005. East African Community Secretariat Regional E-Government Framework (Draft). Secretariat Arusha, Tanzania

Fan, S X., Zhang, X and Rao, N. 2004.“Public Expenditure, Growth, and Poverty Reduction in Rural Uganda.” DSGD Discussion Paper No. 4.Washington, D.C.: IFPRI.

Government of Uganda, 2003. National Agricultural Education Strategy, 2004 – 2015. Final Draft Policy

Government of Uganda, 2002. Information and Communication Technology Services and Systems: Policy and Master Plan. Ministry of Foreign Affairs Government of the Republic of Uganda

Kwemara W. N. and Mayende J., 2006. Opening New frontiers for Equity and Quality Education through Open and Distance Learning. Report on the Uganda National Consultative Forum on Open and Distance Learning Hotel Africana, Kampala, Uganda

Liyanage, H. 2005. ‘Evaluation Report on the Reflect ICTs Project’, ActionAid: London, http://www.id21.org/rural/r3hb1g1.html; id21 research highlight: Empowering people through information and communication technologies.

Makerere University Information and Communication Technology: Policy and Master Plan, 2004.

MFPED (Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development), 2007. National Budget FY 2007/2008

Ministry of Education and Sports National Agricultural Education Policy 2003. National Agricultural Education Strategy 2004 – 2015 Final Draft Policy.

Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development (2000): Plan for Modernization of Agriculture: Eradicating Poverty in Uganda, Kampala

Prakash S., 2000. Uganda: Information Technology and Rural Development. World Bank. Washington D. C.

Stephen R. and Min Shi, 2001. Distance learning in Developing countries: Is anyone measuring cost-benefits. www.Techknowlogia.org

Related information

The Main Page on Tech-MODE in SSA is Tech-MODE_in_SSA

For brief information on the country studies see the poster presentation: Tech-MODE Poster

For information on agricultural open educational resources (AOER) see the poster presentation:

AOER Poster

For a Synthesis Report on all eight country studies see Tech-MODE Synthesis

For the Country Study on:

- Cameroon see Tech-MODE in Cameroon

- Ghana see Tech-MODE in Ghana

- Kenya see Tech-MODE_in_Kenya

- Nigeria see Tech-MODE in Nigeria

- Sierra Leone see Tech-MODE in Sierra Leone

- Tanzania see Tech-MODE in Tanzania

- Uganda top of site see Tech-MODE_in_Uganda

- Zambia see Tech-MODE in Zambia

Distance Learning for Agricultural Development in Southern Africa

Rainer Zachmann, Mungule Chikoye, Richard Siaciwena, Krishna Alluri

In 2001, the Commonwealth of Learning (COL), Vancouver, Canada, and the In-Service Training Trust (ISTT), Lusaka, Zambia, initiated a program for agricultural

extension workers in Southern (and Eastern) Africa to develop and deliver distance-learning materials. Participants from Namibia, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia produced

materials, pre-tested them with prospective learners, improved the materials in a workshop in 2002, and implemented pilot programs in their countries in 2003 and 2004.

Paper: http://www.tropentag.de/2005/abstracts/full/284.pdf

Poster: http://www.tropentag.de/2005/abstracts/posters/284.pdf

ICT/ICM Human Resource Capacities in Agricultural Research for Development in Eastern and Central Africa

Rainer Zachmann, Vitalis O. Musewe, Sylvester D. Baguma, Dorothy Mukhebi

Human capacities are lagging behind the quickly evolving information and communication technologies and management (ICT/ICM). Therefore, the Regional

Agricultural Information Network (RAIN), one of the networks of the Association for Strengthening Agricultural Research in Eastern and Central Africa (ASARECA),

commissioned an assessment of ICT/ICM human resource capacities and related training needs in the context of agricultural research for development. The assessment

included visits and interviews, questionnaire surveys, and desk studies at national agricultural research systems in the ASARECA subregion. We found a general lack of

ICT/ICM policies which has serious consequences, and leads to a wide variety of training needs. Fortunately, most training needs can be satisfied with resources available

locally, in-house, in the country, or in the ASARECA subregion.

Paper: http://www.tropentag.de/2005/abstracts/full/276.pdf

Poster: http://www.tropentag.de/2005/abstracts/posters/276.pdf