Treaty of Waitangi/Wai1604

Ōhotu 6F1 (six acres), an area called Kaikākā by its owners, is situated near the confluence of the Mangawhero River and Hāpokopoko Stream, on either side of Parapara Road.63 It was created in 1911 after tūpuna of the current owners objected to the sale of a larger block, and applied to have their shares partitioned out. Claimant Jacqueline Flight acknowledged that such a tiny block might be ‘insignificant and worthless to some’, but to her whānau it is far from that:

We are descendant of the Ngati Waikarapu Tribe who once populated the valley and ranges of what is now called the Parapara. There were numerous Pa scattered over this vast area of thick bush land. The Urupas of Te Parapara, Puketapu and Ngahura are the last resting place of our Tipuna. … The lower part of Kaikaka … has the Mangawhero River flowing around it. Our Ancestors gathered there to do the daily domestic chores such as washing clothes and bathing their Mokopuna. They would set their hinaki’s and the eels and trout always kept our families fed. This activity is still practised by our whanau today. … The 3 acres above the road that is also Kaikaka is the ideal spot to view the remnants of what were once the vast Ohotu and Parapara Blocks. … There are many of our ancestors buried all over these lands and Kaikaka is no exception. The ashes of two of our Uncles are scattered there. The Pito and afterbirth of Moko’s have been placed there over decades. Our children and their children’s Pito and afterbirth are there. … The Mangawhero is our spiritual river, it plays an important role in our daily lives, it is our holy water. We have fond memories of swimming, playing and growing up there. … Often whanau members would take away with them a container of this water for spiritual clean[s]ing.64 The current owners of Ōhotu 6F1 brought their claims about the block to our attention towards the end of the Whanganui hearings process, and their evidence at that stage was limited. Some further information has, however, since come to light in the course of reporting on this claim.65 The case is interesting because it exemplifies the kinds of pressure that Māori were under to sell their land in the early twentieth century, and how partitioning out interests from large blocks could result in continued Māori ownership of only a small fragment, too isolated and too small for habitation. Then, activities of the Crown and local authorities could diminish and adversely affect even such insignificant acreage.

26.4.2 What the claimants said

The owners of Ōhotu 6F1 (Wai 1604) contended that the Crown failed to actively protect their interests in Ōhotu 6F1, and allowed the native land laws, public works regime, and, later, the actions of other authorities to render their land economically unviable and impede their use of the block.66 They argued that this has threatened their spiritual ties to the land, and restricted their ability to exercise tino rangatiratanga.67

The Crown made no submissions on this claim.

26.4.3 The creation and alienation of Ōhotu 6F

In 1897, the Ōhotu land block came before the Native Land Court for title investigation, and when the court subdivided it between hapū,68 Ōhotu 6F (227 acres) was awarded to Waikārapu and Tūmataira, of Ngāti Pāmoana; 202 owners held interests in the block. Parapara Road later went through the block’s south-west corner, taking 7.5 acres.69

The owners did not pay survey costs of £28 5s 9d charged against Ōhotu 6F in January 1903, and so in February 1909 the Native Land Court awarded to the Crown 39 acres in lieu of payment. The Crown’s 39-acre partition became Ōhotu 6F1, and the balance of the block became Ōhotu 6F2.70

At the end of 1909, the Aotea District Māori Land Board approved the owners’ application to lease out Ōhotu 6F2.71 The block had not been leased for a full year when a local farming family, the Glenns, applied to purchase it at 34 shillings per acre, apparently the government valuation.

The land board held a meeting of owners in December 1910 to consider the Glenns’ offer. Minutes of the meetings record that a number of prominent owners attended – Hāwira Rehi, Arama Tinirau, Eruini and Tiemi Te Wiki, and Rēneti Te Kaponga, along with a Mr Forsyth, the husband of another owner, Hārete Rīpeka Utanga. Tinirau chaired the meeting.72 Te Kaponga and Tiemi Te Wiki did not agree to the proposal, and said the owners needed a conference to discuss matters like the price, whether to retain the block themselves and farm it, or whether to lease it. Leasing was preferable to selling, in Te Wiki’s view, and he added that his remarks did not apply only to the block in question. The meeting was adjourned for a few hours to give the owners a chance to discuss the issues.73

When the meeting resumed, Tiemi Te Wiki presented the owners’ counter offer: they would sell the land for 50 shillings per acre (substantially more than the offered price), but if the Glenns rejected this, they would continue to lease the land. Perhaps in an attempt to discourage the meeting from selling unrepresented owners’ interests, he pointed out that the block had almost 190 owners, and the majority of them were not at the meeting. Two owners, Eruini Te Wiki and Rīria Rāwhiti, asked for their interests to be partitioned out. Forsyth commented that the road through the block increased its value. The Glenns’ lawyer, however, pointed out that the current lease was worth 30 shillings per acre, whereas the purchase offer was 34 shillings per acre, and would include the 39 acres transferred to the Crown for survey liens – the Glenns would pay the Crown the survey debts, and would also pay the Māori owners for the 39 acres. In the end, the meeting adjourned again to give the owners more time to consider their options.74

It seems likely that owners held their own hui, but we have seen no record of that. A final meeting of assembled owners was held on 19 December 1910 with 11 owners in attendance. A summary report of the meeting records that Tinirau again chaired. Rewi Rēneti put forward the proposal to sell, seconded by Tiemi Te Wiki. The price was 34 shillings an acre, including the Crown’s 39 acres. This time the resolution was carried, although the report gives no account of any discussion. The shareholding of those present at the meeting was 36.5 out of 300 shares.75

Not all of the owners were happy with the sale. Rora Te Oiroa Pōtaka asked the land board ‘not to confirm the resolution so far as it relates to her interests and to those of her family’, but later withdrew her objection.76

Rāhera Tīweta (also known as Rāhera Huinga) also opposed the sale. She attended the meeting on 19 December. She applied to have her family’s interests – amounting to six acres – partitioned out.77 Their interests became the new Ōhotu 6F1. Survey costs for the partition were £7 6s.78 This done, Ōhotu 6F2 was transferred into the ownership of the Glenns.79

26.4.4 Difficulties in using and protecting Ōhotu 6F1

Owners agreed on the location of Ōhotu 6F1, placing it next to the Mangawhero River.80 As map 26.4 shows, this block was bisected by Parapara Road. Witness Jacqueline Flight told us that her eldest brother ran a hobby farm on the block from 1975 to 1979, but it was uneconomical.81 George Pōtaka said that he had attempted to establish a plantation of pine trees, but found it difficult to navigate the necessary bureaucratic processes.82

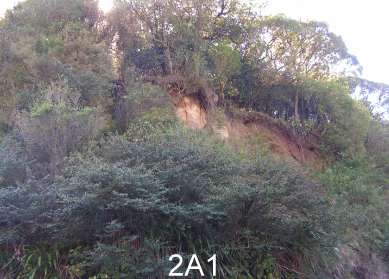

The claimants described the challenges of dealing with local and central government authorities whose actions have affected the land. Mr Pōtaka provided evidence that large pipes were laid under Parapara Road during his childhood, channelling water from the road and neighbouring block. The problems caused are significant, with ‘large crevices gouged into the hillside below the road’, water pooling on the land and creating an ‘unusable swamp’, and causing ‘many of the pine trees to become unstable and rot’.83 Mr Pōtaka has visited the local council on more than one occasion about this issue, but without result. He further stated that during the 1990s, Horizons Regional Council laid brodifacoum as possum bait around the block, despite the owners having informed the council that they did not want poison to be laid because they still used the land as a camping site.84

In recent years, the owners entered into discussions with Transit New Zealand regarding the proposed realignment of Parapara Road at Ōhotu 6F1.85 The road makes a very sharp turn as it passes through the block, and has been the site of many accidents over the years.86 To straighten the road, Transit New Zealand needed to acquire nearly three acres of Ōhotu 6F1, which the owners indicated they might agree to if the land could be exchanged for a similarly sized block.87 We do not know how Transit New Zealand or its successor, the New Zealand Transport Agency, viewed this request, but the issue remained unresolved at the end of our hearings in 2009.88

26.4.5 Conclusion

Those owners who voted to sell Ōhotu 6F2 held only a small minority of the shares. On the other hand, there was considerable discussion among owners as to what to do with the land, with prominent local men taking an active part in the decision. It seems likely they consulted with other owners during the three-day adjournment between meetings. We do not know why, in the end, they agreed to sell, although we can say with some certainty that they were not in a position to farm it themselves. The lump-sum purchase price was presumably simply more desirable to most than drip-fed rent on a long-term lease.89

The remnant partitioned out as Ōhotu 6F1 is bisected by Parapara Road, but Rāhera Tīweta presumably had her own reasons for choosing these particular six acres. Perhaps she thought that proximity to the road would make the site suitable for a dwelling. Perhaps she was also influenced by its position beside the Mangawhero River and the view it affords over ancestral lands. These were factors that Jacqueline Flight said contributed to the block’s significance.90 However, proximity to the road has brought problems over the years. Water piped away from the road and onto Ōhotu 6F1 has led to flooding, and now land is sought to reroute the road.

Parapara Road is a State highway, so its management is in the hands of Crown agencies. Those responsible for the road must have laid the pipes that have damaged Ōhotu 6F1 and caused flooding. It appears that this occurred without permission, or compensation for the adverse effects. There are also pipes directing run-off from other farmland onto Ōhotu 6F1. They may be on private land, although it is not clear from the evidence presented who owns them.91

The lack of definitive evidence about past or present processes concerning the land and the maintenance of the road precludes our making findings and recommendations here. However, we do encourage the Crown to facilitate meetings between the claimants and agencies working in Ōhotu to discuss rehabilitation of the damage to the block. It is also critical that any purchase of Ōhotu 6F1 land to reroute Parapara Road occurs only if the owners are willing, and suitable land is made available by way of exchange.