TRU/Law3020/GroupU

Contents

- 1 Legal Perspectives:Thomas v Norris, [1992] 2 CNLR 139

- 2 Natural Law, St. Thomas Aquinas

- 3 Legal Positivism, John Austin

- 4 The Separation Thesis, H.L.A Hart

- 5 The Morality of Law, Lon Fuller

- 6 Law as a System of Rights, Ronald Dworkin

- 7 Liberty & Paternalism

- 8 Law and Economics, Susan Dimock

- 9 Feminist Theories, Catharine MacKinnon

- 10 Critical Legal Studies / Critical Race Theory

Legal Perspectives:Thomas v Norris, [1992] 2 CNLR 139

Purpose of this Wiki

This wikipedia entry is designed for a Legal Perspectives class at Thompson Rivers University, Faculty of Law. Each group has been assigned a particular legal case with the task of applying various theoretical perspectives. Our group consists of Dalene Visser, Tracy Vu, Germaine Watkins, James Wegener and Mike Wolfson; our assigned case is Thomas v Norris.

Facts of Thomas v Norris

The plaintiff, David Thomas, is a 35 year old aboriginal man and a member of the Lyackson Indian Band. He is suing for damages as a result of being subject to the torts of assault, battery and false imprisonment. The defendants consist of seven men, of which four men belong to the Cowichan Indian Band, one man belonging to the Halalt Indian Band, and one man whom is a non-status Indian and is not a part of any band.

Late in the afternoon of February 14, 1988, Thomas was kidnapped from a friend’s home and taken to the Somenos Long House, a community house of the Cowichan Indian Band. There the defendants forced Thomas into their initiation ceremonies to become to a spirit dancer of the House. As part of the initiation ritual, the men dug their fingers into Thomas’ stomach and bit into his flank while holding him up in the air. He was bathed in a cold creek and whipped with cedar branches. He was confined without food and given only minimal amounts water to encourage a hallucinatory state. After 4 days, he was released. The plaintiff claims that he was injured and wrongfully imprisoned while by being forced to participate in these ritual ceremonies. Medical evidence shows he suffered from dehydration and had multiple contusions on his body.

The defendants presented three defenses against the plaintiff's allegations.

1. They did not have sufficient intent to harm the plaintiff.

2. The plaintiff consented to their actions.

3. They argued that the practicing of the Coast Salish Spirit Dance is an aboriginal right and therefore protected under s. 35(1) Constitution Act, 1982.

The court framed two key issues in the case.

1. Whether the defendants assaulted, battered, or falsely imprisoned the plaintiff (meaning with the nesessary intent and without consent)

2. Whether spirit dancing (and the ceremonial initiation) is a protected aboriginal right under s. 35(1), rendering inoperative the common law torts of assault, battery and false imprisonment.

The courts quickly dismissed the first issue, and with it the first and second defenses. There was simply no evidence to suggest a lack of intent to cause harm and no evidence to suggest the plaintiff consented in any way. The court emphasized the fact that when the plaintiff arrived at the hospital he was notably dehydrated, had multiple contusions and expressed a fear of being taken back to the Long House.

In dealing with the constitutional argument the court sets out to define the nature and the scope of the argued right in s.35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982. The defendants claim that because the spirit dance is a constitutionally protected right they are immune from civil claims. The court did not uphold this argument. Reviewing the common law, the court found that there is not sufficient evidence to assert an aboriginal right here. Though it did acknowledge that an aboriginal right may have existed for some dances, this kind of dance would be extinguished by the English Law as it conflicts with statutory and common law that protects individuals from this type of abuse. Even if it was accepted that this spirit dance is a constitutionally protected aboriginal right, the court holds that these rights are not absolute and are limited by the criminal and civil laws. If this harmful conduct cannot be separated from spirit dancing, then spirit dancing cannot be an aboriginal right recognized by law. The rights or freedoms under s. 35(1) do not enjoy immunity for criminal acts or tortious conduct. In its reasoning the court also discusses the nature of rights and freedoms enjoyed by all Canadian citizens. These rights, the court asserts, cannot be reduced because they are “original” freedoms. Therefore, Mr. Thomas enjoys rights that are inviolable and are not subject to the collective rights of others. The decision is for the plaintiff, and Mr. Thomas was awarded damages.

Foreword

This case is multi-layered, as we see many different legal issues occuring at the same time. A central issue is that of aboriginal law competing with "dominant white male" law. To place this in its judicial context, it is worth nothing that this case takes place soon after R. v. Sparrow, [1990] 1 S.C.R. 1075, but before R. v. Van der Peet, [1996] 2 S.C.R. 507 and Delgamuukw v. British Columbia [1997] 3 S.C.R. 1010. The issue of aboriginal rights and how to address them is still new and developing at this time, despite the fact that it is Constituionally protected under s. 35(1). This should be kept in mind when considering the judge's analysis of the aboriginal rights defence.

Another conflict that is present is that between codified rights, affirmed in the Constitution Act, 1982, and the common law. The defendants are arguing that they are protected by s. 35(1), and that this justifies their actions as the spirit dance rituals are an aboriginal right. The plaintiff is arguing that his individual rights are first and foremost protected by well-entrenched tort law. The judge makes note that the individual rights present in this case are reflected in the Charter, but he acknowledges that the Charter deals with protection of an individual's rights from the state, so it does not apply here; however, the underlying values of the Charter can still be seen. Though the judge dismisses the claim that there are any aboriginal rights present, his comments after this conclusion raises some concern with his analysis. The judge decideds to test aboriginal rights on their own merit, as if they were found and as if they would not have been extinguished by legislation. In doing this, the judge goes as far to say that even if there was aboriginal rights it would be inconsistent with the common law rights so it would not hold the force of law. Yet, as we know, legislation trumps the common law, and the Constitution is the supreme law of Canada. This should be kept in mind when considering the judge's analysis of the aboriginal rights defence and the individual rights analysis.

Last, we are looking at a case where the defendants are aboriginals, relying on aboriginal law - which are communal rights, while the plaintiff is also an aboriginal, yet he is relying on the common law - individual rights. This issue combines aspects of the previous two. The aboriginal plaintiff disregards his aboriginal culture and the claim that there are aboriginal rights present, and instead goes to the "dominant white male" common law to obtain damages and to show that this aboriginal practice is wrong. This should be kept in mind when considering the judge's analyis of individual rights.

These issues are worth keeping in mind when looking at the following theories and how they apply to this case.

Natural Law, St. Thomas Aquinas

A major proponent of natural law, Thomas Aquinas (Aquinas), asserts that natural law is derived from a higher, non-human source (God, nature/natural order, or reason). This source is essential to the concept of true law, which are laws that must be obeyed for the purposes of achieving justice, fairness, and morality for everyone. According to Aquinas, morality and goodness is inherent in the law.

Aquinas also suggests that law may viewed as being teleological such that all things have a proper function or end function and the law can only be understood with that purpose in mind. Aside from serving this purpose, Aquinas asserts that in order for a law to be valid, it must contain four characteristics. First, the law must be directed to the common good. This means that the law must take into account the good of the entire community as opposed to the good a specific individual or even the most people. In this first branch, there is also an analysis on order and the common good. This means that happiness is only possible in a stable and orderly society. Second, the law must follow practical reasons in that it should direct its citizens as to what they must so and the steps they must take in order to reach the common good. Third, a valid lawmaker must make the law. It is believed that political authority of the ruler over the ruled is natural and some are naturally fit to rule others while some are naturally fit to follow. It is asserted that the natural rulers know what is in the common good, and what will achieve universal happiness. These natural rulers have the means to pursue the goal i.e., threats, coercion, and punishment. Lastly, the law must be promulgated meaning that the law must be written and known to those to whom it applies. A person cannot be held responsible for a crime if they are unaware of what the law is.

The role of judges is to make a right decision about what is “just” and fair. Just judgments therefore require prudence, an inclination of justice, and authority. Moreover, in interpreting the law, it is believed that the abiding by the spirit of the law is more important than abiding by the letter of the law. According to Aquinas, it is sometimes acceptable for judges to step outside of the “letter of the law” in exceptional circumstances in order to uphold the spirit of the law, which is always the aimed at the common good.

Application to Thomas v Norris

We can see various natural law concepts that are present in Thomas v Norris. In examining whether laws are valid from a natural law perspective, it must be determined whether they meet the four criteria set out by Aquinas.

First, it must be determined whether the law is aimed at enhancing the common good. There are some “goods” that are recognized as being essential to all humans such as self preservation, procreation, living in society and exercising spiritual and intellectual capacities. As we have mentioned previously, there are two sets of laws that present in Thomas v Norris, the laws of the aboriginal band and the common laws of Canada. The aboriginal rights as ascertained by the defendants that are constitutionally protected by s. 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982 (CA, 1982). It can be argued that aboriginal rights, specifically the right to maintain a tradition of spirit dancing is aimed at enhancing the common good of a specific aboriginal band. The purpose of spirit dancing is to help the individual reach a higher stage of spirituality. Tying this into the common good, it can be argued that aboriginal rights are communally held, therefore the right to spirit dance is aimed that enhancing the good of the entire bad. However, Aquinas would argue that these ‘laws’ and practices held by the Cowichan Band are not necessarily aimed at the “common good” of the entire community in the context of Canadian community. Rather, they are aimed only at the good of the Band, and this would not qualify as being directed to the common good because Aquinas would say that it is not enough to be directed at the good of a specific individual (or a specific band in this case) or even most individuals. We believe that Aquinas would be more inclined to agree with the court in this case in that the common good should be directed at the larger community, the Canadian community. In agreeing with the court, we can see that Aquinas would support the common laws of Canada. Therefore, the common law would also meet the first requirement of valid law because as the court states these rights are "original freedoms" which are concerned with the order of society including public safety which can be classified as a common good.

Second, the law must follow practical reasons in that it should direct its citizens as to what they must do and the steps they must take in order to reach the common good. In analyzing this characteristic in terms of aboriginal rights, there are practical steps that need to be followed in order to commence with the initiation, this includes attaining consent from an elder of the band to have an individual to initiated, and then to attain permission from a family member of the individual. This sets out the steps as to how an individual can be grabbed in order to be initiated, furthering their spirituality. By enhancing their spirituality, it adds to the overall good of the band. In terms the common law; the torts of battery, false imprisonment and assault are explicit in that one’s rights and body should not be interfered with without their consent. We would suggest that this is a very clear step in reaching the common good, including individual and public safety.

Third, a valid lawmaker must make the law. It is believed that political authority of the ruler over ruled is natural and some are naturally fit to rule others while some are naturally fit to follow. It is asserted that the natural rulers know what is in the common good, and what will achieve universal happiness. In addressing this issue, the Spirit Dance would likely meet the requirement of being made by a ruler in the community. We would suggest that elders within each band have the ability to consent to and oversee the ceremony to ensure that it is carried out correctly in accordance with tradition. In this case, an elder of the long house oversaw the initiation; Leonard Peters testified "as an elder he was responsible for the way in which it [the initiation] was carried out". Aquinas might agree that an elder is a valid lawmaker. The lawmaker does not merely carry out the will and wishes of the community – they are natural rulers and know what is in the common good as was the case here. In the context of aboriginal rights, there may be a strong argument in favour of seeing band elders as lawmakers. On the other hand, the common law is judge-made law which did not exist during the time of Aquinas and is a difficult thing to fit into the natural law scheme. Aquinas prefers laws are legislative; however, judges play an important role in applying natural rights therefore if a written law runs contrary to the natural rights the judges will not apply the written law. An argument can also be mounted on the basis that judges are in a position to know what is within the common good and have the ability to punish those who do not abide by the law.

Lastly, the law must be promulgated meaning that the law must be written and known to those to whom it applies. A person cannot be held responsible for a crime if they are unaware of what the law is. Neither aboriginal rights or common law are written down in a codified manner; however, we acknowledge that common law decisions are often written by the judges and can be readily accessed by the public. On the other hand aboriginal rights and laws are generally circulated orally and therefore not written and are generally only known by those who are in the band. We would suggest that both the defendant and the plaintiff were aware of both sets of laws. This is evidenced by the fact that the plaintiff knew of the aboriginal right and his individual rights. Also, that the defendants knew of the individual rights to be free from interference but explicitly stated that their rights would be immune the common law.

Overall, we believe that Aquinas would agree with the court’s application of the case. Although the judge limits the constitutionally protected rights of the aboriginal band, he does so in order to protect natural freedoms of Thomas, in turn, protecting the common good. We also think that Aquinas would agree with the conclusion of the case because he might have viewed the interference of Thomas' individual rights as acceptable based on the collective rights of the band especially if the interference with Thomas' individual rights lead to a greater fulfillment of his intellectual and spiritual capacities. Aquinas would have seen this interference as necessary for the common good and therefore not illegal.

Legal Positivism, John Austin

Legal positivism is a theory that started as a refutation to natural law. The most important difference between these two theories is that where natural law asserts that morality is inherent in the law, legal positivism separates law and morality. This separation is called the “separation thesis”. Both John Austin and Thomas Aquinas believe that there is a moral obligation to obey the law. For Aquinas, there is an obligation to obey the law because the law is inherently moral. However, for Austin there is only a moral obligation to obey valid law. According to legal positivists, a law can be valid even if it is not moral.

There are three formulations of law: God’s law, positive morality or norms, and positive law. God’s law is the law of religion. Positive morality is essentially norms that include manners, customs, club rules, international law and constitutional law. Positive law asserts that a law must contain three elements. First, the law must be a command. Second, the command must be issued by superiors to subordinates—this sovereign who is an individual or a group that the majority of people are in a habit of obeying. Lastly, the law must be backed by sanctions. The last requirement for a valid law means that it is difficult to place regulatory legal rules in the legal positivist theory because they lack sanctions.

Judicial decisions are viewed by Austin as being specific commands which are more along the lines of positive morality and therefore they are not really laws but will be tolerated if not overruled. Laws can be empirically proven.

Legal positivism has been re-imagined by several theorists including Bentham, Hart and Raz. Their interpretation of the theory is generally called legal radicalism. Hart emphasizes the separation of law and morality which in turn increases one’s ability to challenge the law. However, they do not characterize the law as a command. Therefore, if there is too large a disparity between morality and the law it by be necessary to disobey the law. The validity of a law is based on the rule of recognition. People have to apply the rules and they have to believe that they ought to apply the rules. Bentham considers utilitarianism to be the guiding principle in making law. Raz views law as authority and this authority is acceptable when it helps citizens in some way.

Application to Thomas v Norris

The positivist approach does not seem very prominent in this case. Legal positivist would have framed the issues based on whether there was a valid law to be applied, and, if so, it should be so applied by the judge. In this case, Austin would have viewed that any right protected by the Constitution would trump any common law right. They might have agree with the judge’s assertion that the aboriginal right was not made out in this case because it did not meet the appropriate evidentiary standard, in which case the common law should be applied.

Austin would have approached this case by assessing whether there was a valid law that had to be applied. Immediately, the case runs into difficulty since there are effectively three different laws applying to the case, there is common law tort law, there is the constitution and there is aboriginal law. It is unlikely that any of the three types of “law” would meet Austin’s pedigree test. Tort law is a type of positive morality not valid law in Austin’s scheme because it is judge made law and judges are not sovereigns issuing commands. Aboriginal law is also difficult to assess from this perspective because the law is not clearly defined by the case however it is unlikely that it would have been understood to be a valid law in Austin’s scheme because there is not sovereign who society is in a habit of obeying—this is evidenced by the fact that Mr. Thomas decided to apply for relief under the common law of tort instead of obeying the process. Lastly, there is the aboriginal right entrenched in s. 35 of the Constitution. This is also a problematic “law” in Austin’s formulation the identity of the sovereign is difficult to ascertain in our society, however, if we state that the Constitution is a command issued by a sovereign there is also the issue of sanctions. There are remedies built into the Constitution when it is breached, however, it seems unclear whether there are clear sanctions for infringing an Aboriginal Right in this case since the claim it as a defense to a tort allegation.

Therefore, from Austin’s perspective there are three equally problematic laws interacting with each other in this case. Likely, Austin would have dismissed the Aboriginal Law outright. The question would have been between the common law and a constitutionally entrenched right which has to be defined by the common law. Austin would have stated that because tort law is a type of positive morality it should give way to the Constitution. In this way, Austin would have framed the issue as relating to the constitutional right claim and would have disregarded all of the policy implications that are considered by Justice Hood. These considerations are not law and they violate the separation principle by trying to influence a finding in law with moral considerations. Therefore, if an Aboriginal right had been established then the moral or policy considerations that the Justice considers around protecting individual rights would not have been considered by Austin. It would have been a pure approach of whether the Aboriginal Right can be made out on the tests.

The legal radicals, Hart, Bentham, and Raz, would take a more critical approach to the law. They would not have taken such a strict look at the application and obedience of the law that Austin does. They still endorse a separation of the law and morality; however disobedience of immoral laws might be necessary. This can be tolerated because laws are not commands.

Hart would have approached the issues also by asking whether there was a valid law however the validity of the law is based on the rule of recognition. In this case, the analysis would be clear Justice Hood appears to have a strong disinclination to establishing an Aboriginal Right. This would likely lead Hart to the conclusion that the Justice does not meet the psychological requirement of believing that he “ought” to apply the constitutional law. Therefore, the only law that Hart would have considered would be the common law of tort.

Bentham would have considered which law best meets the goal of utilitarianism. Morality is not a question and in this case Aboriginal people are in the minority of society. Therefore, more people would likely benefit from not finding an aboriginal right and applying only the common law.

Raz would have looked that whether application of any law would help people act better than without the application of the law. From the facts of this case it is difficult to determine whether people would have acted differently if it were clear that one law of the other would have applied.

Austin might have agreed with the outcomes of the case, if it were clear that an Aboriginal Right could not be made out. However, he would likely not agree with much of Justice Hood’s reasoning because his reasoning considers morality. Justice Hood clearly stated that even if the test for an Aboriginal were met such a right would still have been limited by the common law he wrote, "If such conduct [civil wrongs] cannot be separated from the spirit dancing, then in my opinion spirit dancing is not an aboriginal right recognized or protected by the law." This use of moral principles to limit an entrenched right would have been criticised by Austin because it violates the separation thesis.

From Hart’s perspective he would have agreed with the outcome of the case. He would have agreed because he would not have understood the Aboriginal Right as meeting the rule of recognition threshold for a valid law—therefore the only valid law to be applied would have been the common law. While, he would have been critical of the use of morality similar to Austin he would have agreed with the outcome.

Bentham would also have agreed with the outcome however not the reasons that Justice Hood provided. He would have considered the interest of more people protected by enforcing the common law and not conferring an aboriginal right.

The Separation Thesis, H.L.A Hart

Hart is a legal positivist. Like Austin, he believes law and morality are two distinct things, though they may run coincidentally parallel at times. However, Hart's separation theory is quite different from Austin's and is in itself a critique of Austin's legal positivism. Whereas Austin saw law as coercive, as coming from a command and enforced by punishment, Hart recognized there are many kinds of law. For example, Hart points out the rules of games, like football. These kinds of rules are not unlike many laws in that they are enabling or regulating; they set out how things can be done. Contract law is like this. There are laws that set the terms for how contracts can be formed, and if they are not formed then there is simply no contract. This is not like a punishment, it is just a failure to create a contract, a failure to accomplish the act within the legal rules.

For Hart, law is a rule governed practice. Laws are rooted in the rule of recognition, meaning that they are respected and obeyed by the majority of the people for most the time. This could be because the laws in themselves are good or because they are backed by a legitimate authority. But, contrary to Austin, laws are binding on both citizens and the sovereign. Laws can grant rights and duties, and these are protected by the sovereign. This places a duty on the sovereign. Further, law itself is what grants authority to the sovereign. One need only look at our current law to see how this is true.

For Hart, laws include both legislation and the common law. Laws are expressed in general terms, and as such some factual situations may fall within a grey area, which Hart calls the penumbra. For Austin, only the settled core, these general terms, are law and judges settle these penumbra cases by appealing to social aims. Hart disagrees. A judge will draw from the terms of the rule governed practice, that is, general laws and principles that are recognized and obeyed, and from them will decide a penumbra case. Unlike Austin's settled core, these principles are flexible. Not every principle applies to every law, and the principles themselves may change over time. A judge must determine which principals are relevant and apply them to the case. Judicial precedence is really just making law from law, not from appealing to social policy, personal discretion or morals. In this way, judicial decisions are legitimate law.

Application toThomas v Norris

Thomas v. Norris is a penumbra case. Justice Hood clearly appeals to the principles of fundamental justice in his individual rights analysis. Though he finds no aboriginal rights present, as there is not sufficient evidence to establish any, he goes on to argue that even if there was aboriginal rights present they would not be upheld by the law because they would conflict with fundamental individual rights. He points out that the law has never allowed, or given the right to subject another person to assault, battery or false imprisonment. That is because it is a principle of fundamental justice that these rights must be protected first and foremost. The fundamental justice here is part of rule of recognition. These principles are respected and obeyed by the majority of the people, and have been recognized and entrenched for an extended time.

A key problem with Hart's separation theory, in relation to Canadian law, is that it does not have a proper way to deal with aboriginal rights. This case deals with competing rights, the rights of the individual and aboriginal rights. Hart does not give any guidance on how to resolve the conflict between these rights. Hart does not give any guidance on how to weigh competing principles of fundamental justice. He states that not all principles will apply to every case or every law, but how is a judge to discern which principles apply to this case and which are not relevant or are superseded?

Hart would likely not recognize aboriginal rights. At this time in law, the concept of aboriginal rights and how to address them is still relatively new and still developing . This is a problem as aboriginal rights are backed by a legitimate authority, the Constitution, but the tests to determine if there are aboriginal rights present are all developed by the common law. Addressing aboriginal rights is still an issue of contention in the courts. It is likely that aboriginal rights would not meet the rule of recognition as at this time they are not well respected and obeyed by the majority. A key problem remains, Canada is taking efforts to address aboriginal rights but Hart has given no indication of how to incorporate them into the existing principles. His approach accepts that principles can change over time, but how does it address aboriginal rights which are just coming to the forefront and have not been properly recognized? When is a new principle accepted and when is it too early to accept? How will a judge know? These shortcomings perhaps make Hart's approach not much better than Austin's, who says that judges will look to social aims to resolve penumbra cases. At least Austin's approach gives some light on how a judge may decide a case like this.

Overall, Hart would appeal to the principles of fundamental justice, which would include the protection of individual rights like safety of being, so he would likely come to the conclusion quite quickly that the defendant's were in the wrong and should pay damages. The common law around these torts are well established. The defendants use aboriginal rights to defend their actions but if Hart does not recognize them then they are left with no defense. One might ask if this is actually what the judge does. He runs through the Aboriginal rights tests but is it really just a disguise for his ultimate conclusion, that they really have no force here anyways.

Hart would come to the same conclusion as Justice Hood, but by a different analysis. Hart would likely not recognize aboriginal rights. Justice Hood addressed the aboriginal rights issue, and recognized that they also deserve protection, but determined that there was no aboriginal right present and even if there was the rights of the individual here are still of such importance that they would come first. Hart and Justice Hood would agree on protecting the individual rights, as it is a fundamental principle of justice and must be protected. However, Hart could not deal with aboriginal rights in a suitable way, as is required by Canadian law. As mentioned above, some might argue that Justice Hood does not address them in a suitable way either, but a key difference would be that Hart would likely not even run the tests for aboriginal rights.

Another way that Hart’s theories can apply to Thomas v. Norris is that it could be seen to compel the grabbing of Thomas regardless of the fact that it is illegal. Hart’s contention is that when there is a clash between law and morals, if the law is evil enough, it is valid to disobey it. The defendants likely view the court’s decision as an existential threat to their whole system of cultural values. The Spirit Dance is a time-tested way of respecting the collective rights of the community and resolving disputes. It arguably would be against the moral values of the culture to give up the practice. Hart’s views could justify the continuance of the Spirit Dance despite the court ruling.

This contrast between aboriginal culture and the dominant culture in terms of whether or not morals and law coincide is a good illustration of the ideas behind critical legal theory. The conception of what is “real”, in this case being what is moral, would be seen as part of the “hegemonic consciousness”.

The Morality of Law, Lon Fuller

The Morality of Law is a theory advanced by Lon Fuller. In a critical response to H.L.A. Hart’s legal positivism, Fuller’s key view is that law cannot be separated from morality. The Morality of Law theory has several theoretical positions that set it apart as a legal theory. Fuller contended that the acceptance of legal rules in society was inextricably linked to morality in this way he was criticising Hart’s rule of recognition. This external morality interacts with the internal morality of the law which not only makes the law more effective but also produces order.

According to Fuller, for a law to have inner morality the law must be coherent. For a law to be coherent the law requires reasonableness, rationality, and consistency. This is a direct criticism of Hart’s positivist theory in which Hart states that laws can be immoral and when they are immoral they need not be obey. Fuller is critical of this by pointing out that Hart never defines morality or how immoral laws are to be identified. In contrast, Fuller provides rules that would lead to a poor law. The eight characteristics of when rules fails to be laws include when decisions are ad hoc, when rules are unknowable, when rules are retroactive, when rules cannot be understood, when rules are contradictory, when rules cannot be obeyed, when rules changes frequently, and when there is a disjunction between written and administrated rules.

Fuller suggests the role of judges is to interpret the law in context and with reference to the purpose of the rule. Fuller critiques the HLA Hart's concept of the 'penumbra' and rejects the idea that there is a core of settled meaning. Rather, he suggests that there is a dichotomy between 'easy cases' and 'hard cases'. He ascertains that easy cases are cases in which the purpose can be ascertained whereas hard cases have uncertain or competing purposes. Fuller asserts that judges need to have fidelity to the law in that they should make the law what it ought to be.

Application to Thomas v Norris

In analysing Thomas v Norris, we can see that this case would clearly fall into the characterization of a 'hard case' as there are competing purposes at play. In this case, the competing purposes include advancing the collective rights under the Aboriginal rights and protecting individual rights under the common law. Judges in considering the how to apply purposes they consider the wider principles of society and the wider principles of the law. This is reflected in the case when Justice Hood refers to the fundamental rights and freedoms that underlie the basis of the British law. He draws on these wider principles in order to make a decision between the competing purposes of collective and individual rights. The role of judges is to interpret the law in context and with reference to the rule and the good that it was intended to accomplish. In Thomas v Norris, it can be argued that Justice Hood put a good effort into interpreting both sets of law (common law and statute) into advancing the good that they were aimed at accomplishing. However, he ultimately reached the conclusion that in relation to the wider principles and to maintain order individual rights and a strict application of the common law should be preferred.

In considering what that law is a coherent system and not a series of commands in Fuller’s view he lists eight rules that cause a law to fail. In Thomas v Norris, Fuller would consider whether either the common law or the constitutionally entrenched Aboriginal right fails to be law is based on whether they are coherent which requires reasonableness, rationality, and consistency. In this case, the respondents are arguing for the recognition of a constitutionally entrenched Aboriginal right in Spirit Dancing. To establish whether the law should be reformed to allow the for the right Fuller would assert that the law must be coherent. This coherency means that the law must be reasonable, rational and consistent. In this case, it is likely that recognizing an Aboriginal right of Spirit Dancing is reasonable because it is an extension of a traditional culture. The right can also be seen as a rational extension of s.35(1) and the purpose of the section to secure the interest of Aboriginal peoples. However, the right is inconsistent with the individual rights protected by the rest of the common law.

Fuller’s approach towards Thomas v Norris depends significantly on the approach taken towards characterizing the different interest groups within the case. Fuller argues that the government must respect and understand the limitations of its role in society. The role of law is to uphold the orderly function of society. However, there are certain areas of human activity where the government has no place or authority to intrude on. This is where the function and role of Fuller's morality of duty and morality of aspiration come into play. Lawmakers should not confuse the morality of aspiration with the morality of duty that is the subject matter of law should pertain to the morality of duty by creating a standard of conduct that upholds order rather than the morality of aspiration directed at indidivual action. Fuller strongly believed that lawmakers should exercise restraint in creating regulations governing individual conduct. In doing so the government puts unecessariy constraints on positive elements of humanity. Fuller championed creative exercise of talent, experimentation and freedom of action. If the government does not properly place its inititavies in the morality of duty then there will be an improper application, use and effect of the law.

In applying an advocacy for individual autonomy, Fuller would likely view Spirit Dancing as product of the morality of aspiration. Spirit Dancing requires freedom from government supervision. It is an expression of spirituality and is akin to many of the virtues of humanity so appreciated by Fuller. The decision which penalized the expression of Spirit Dancing can be characterized as government interference into the personal conduct of individuals and on this premise Fuller would have disagreed with the outcome.

On the other hand, taking perspective which promotes the morality of duty Fuller would have agreed that the orderly function of society was upheld in the recognition of the right to security of person. Indeed, the fundamental right of security of person is at the heart of an orderly functioning society. This would be an area where the government should most definitely intervene. Thus, it is unclear precisely what outcome Fuller would have favored.

Law as a System of Rights, Ronald Dworkin

Dworkin's starting point is a strong rejection of legal positivism's view that laws cannot be viewed outside their content. Dworkin saw law being an arena of morals and "jurisprudential issues are at their core issures of moral principle, not legal fact or strategy."

He believed that the law consisted of rules, principles and policies. Principles are concepts of fundamental justice in society that support rights and duties and policies are social goals pursued for a certain segment of the population. Policy decisions are best left to legislators in creating statutes, while principles are applied by the judiciary. Legislators consider and are directed by arguments of policy that includes considerations of principle. The policy factor advances goals of a specific or overall community and the consideration of principle advances or protects rights. For example, the policy that "minority rights are to be protected" could be based on the fundamental principle of equality. Rights are individualized while goals are collective. In the example, the right to equality is accorded to every individual whereas the protection of minority rights affects the community of minority members. As the judiciary is concerned primarily with applying principle to rules, Dworkin argues that judges are better than legislators at safeguarding and enforcing rights. Judges are not concerned with policy.

Both the rules of the law and the principles of the law evolve over time separately but in relation to each other. When judges make new rules, their decisions are informed by society's principles that apply to the situation at that point in time. While principles are not created in the same way, they are more akin to simply being present in society in different weights at different times. We can observe which principles are present in society at any given time by observing the rules that are present, by how the principles are discussed in court decisions that create new rules, and by reviewing how the system of rules have been evolving.

When a judge is making a rule, his or her decisions are required to follow the applicable principles in their varying weights that apply to the factual situation. Judges have discretion to make rules, but this does not mean that he or she can be creative as there is only discretion to determine and apply the appropriate principles. When all of the principles that apply to the situation are properly applied to the facts at hand, there is only one "right" answer in formulating the appropriate rule. Even in hard cases that would have been considered part of Hart's penumbra, there can be only one "right" answer that is determined by following the principle. A judge that does not come to the right decision has not applied the principles correctly. A similar fact situation brought before a judge in the future may produce a different rule because the weights of the applicable principles would be different at that point in time. Where an old rule no longer reflects the weights of principles in present society, the rule can be altered, such as in Riggs v. Palmer, where despite its permissibility under the existing rules at the time, the judge held that a grandson would not be able to obtain an inheritance by murdering his grandfather.

Principles are concepts of fundamental justice. They have different weights in different situations in and vary over time. They are not the "super-rules" as envisioned by Hart, although they do inform the development of rules. Hart's super-rules are stagnant and influence the creation of other rules in the same way at all times. Principles vary over time and are somewhat nebulous in that they cannot be ennumerated or even claimed to be valid or invalid. They are simply accepted.

Two Parallel Streams - Rule and Principle

Dworkin's view of the relationship between rules and principles can be envisioned as two parallel streams that they play off and influence each other over time. Principles and rules evolve (flow) together but separately with each one being required for the development and evolution of the other.

Application to Thomas v Norris

The way that Dworkin describes the evolution of principle and law in parallel allows for change and evolution, but it doesn't seem to envision the type of clashing that is taking place between Anglo-Canadian legal principles and aboriginal principles, which are clearly quite different. In Thomas v Norris, there is a clear conflict between the principles of the two cultures at play in this case; specifically, there is a conflict between Aboriginal culture and general Canadian culture. It seems unlikely that there would be a way to reconcile the outcome such that principles from both are adhered to in the creation of a rule to fit the situation.

Principles have different weights according to Dworkin therefore in a case where principles conflict the weight of the principles will lead the correct outcome. This still pre-supposes that all the principles are drawn from the same society. To say that one set of principles better protects the rights of society would be to take an ethnocentric view from one vantage point or the other. Thus, when Justice Hood weighs whether to follow the common law or acknowledge a new aboriginal right he is also weighing the underlying principles of these rules. In this case, Dworkin would argue that Justice Hood came to the correct approach because in weighing the principles from Aboriginal and Canadian culture he considered the principles from Canadian culture to be weightier.

The Constitution Act in s.35(1) is legislated policy and reflects some of the principles of the non-aboriginal culture (and perhaps some of the principles of aboriginal culture). This may be indicating that over time, the principles of the two cultures will approach each other to the point where there would be a true "right" answer in a situation like this. At the present time, it doesn't appear that Dworkin's theory is robust enough to provide a correct answer to the problem.

On one hand, viewed from the perspective of the legal system in which the court finds itself exercising jurisdiction, the decision seems highly Dworkian. The judge discusses in depth the principles of society. If we can imagine that only one set of principles exist or that the principles of the society that created the court should be weighed more heavily where the principles of the two societies conflict, the decision would appear to accord with Dworkin's theories quite nicely. The judge's discretion is constrained by the principles of the dominant "white man's society" and do not allow him to decide in accordance with aboriginal law.

The court discusses quite explicitly what the principles and fundamental values of society are and uses this guidance to determine the correct outcome. The principles enunciated by the judge are related to fundamental rights and freedoms of the individual. In this way, Dworkin would have agreed with the outcome of the case because he would have likely thought that the "stronger" principles had won out. The judge emphatically claims that individual rights out weight communal rights in this case--"that in the contest between them the individual rights of the plaintiff must automatically give way to the communal rights of the defendants." However, I believe that if we look overall at the situation viewed in terms of the principles of aboriginal and non-aboriginal society, the judge is exercising too much discretion in discrediting an entire set of principles for what he believes the outcome should be.

Although not a legal actor, Thomas could be seen as struggling between the two sets of principles: the aboriginal principles and the common law principles. His life is firmly planted in the aboriginal culture through his wife, acquaintances and relations; however, he is relying on the common law to remedy his dissatisfaction with aspects of aboriginal culture. It is likely that his psyche is somewhat tormented in this struggle.

Liberty & Paternalism

Liberty, John Stuart Mill

Generally, the law is used to enforce the moral code of society, to regulate human behaviour, and sometimes used as a coercive institution. These mechanisms are often viewed as restrictions on an individual's liberty to do as they wish and are often backed by threat of imposing sanctions. We must then consider whether or not the law should interfere with individuals’ choices and when these restrictions are justifiable.

The concept of liberty is strongly supported by John Stuart Mill. According to Mill, liberty is the protection against the tyranny of political rulers, where rulers are conceived as antagonistic to the people they rule. The concept of liberty is based on the notion of individuality where the individual has complete autonomy over his/her body and mind. Individuals should be allowed to have the freedom of thought, feelings and expression, which should not be subject of legal consequences if others think their conduct is foolish, perverse, or wrong. The presumption is always in favour of liberty as opposed to a restriction thereof. However, one’s liberty is subject restriction under the harm principle, which is the concept that restriction on individual liberty is only justifiable to prevent serious harm to others. Mill believes that prevention of harm to others is both a sufficient and necessary condition of legitimate inference with the liberty of an individual by law.

According to Mill, the only harm that is worth interfering w/ the liberty of individuals, is the harm of others. When an individual’s actions cause harm to themselves, Mill think it is not appropriate to interfere with these individuals for being unfit. Rather, society should abandon guidance of those who are unfit because they had the opportunity to be molded into person with mature faculties at childhood. Our focus should only be on restricting the rights of those who interfere, harm or have an adverse affect on others. When we make this distinction, it is important to formulate a response that separates harms to self and harm to others and focus merely on the harm to others. This is because the consequences of the individual’s acts not only affect him, but also affect others in society. This concept raises great concern because it is impossible to ascertain that an individual’s actions will never harm others because no person is completely isolated; therefore it is impossible for a person to do anything seriously or permanently harmful to themselves without mischief or harm reaching to their close connections (at the very least). • Where do we draw the line? • If our actions directly/indirectly inevitably impacts others…these actions are therefore subject to restriction…then do we really have liberty?

Mill finds an exception to the rule; he thinks that the right to liberty only applies to individuals in possession of mature faculties. According to Mills, mature faculties includes the capacity of being guided to their own improvement by conviction or persuasion. He believes that children and those who are in a backwards state of society (barbarians) do not get to enjoy the right to liberty.

According to Mill, authority is necessary in order to prevent violent anarchies; however the authority must also be restricted as it is inherently repressive and tyrannical. The concept of individual liberty works to set limits on authority; for example, the recognition of political liberties or rights creates a zone of immunity from government authority in the sense that the gov’t cannot violate one’s individual rights. Government authorities act as delegates of the people, they are elected and are temporary – this creates an apparent reconciliation of interests between the government and the citizens. However, we must be concerned with the tyranny of the majority. Often, the values and ideas of the dominant/ruling class will prevail.

Application to Thomas v Norris

The court's reasoning in Thomas v Norris reflects certain aspects of Mill's theory. For example, the court endorses the defendant's right to perform Spirit Dancing rituals. However, just as Mill believes that the only limit to liberty should be imposed when a person's conduct harms someone else which is called the harm principle, in our case the judge awards damages on the defendants because they had caused harm to Thomas. Because Thomas was directly harmed in our case the common law must step in and condemn their actions which impacts their liberty to perform the Spirit Dance rituals in the manner that they did. The judge makes the point several times that Thomas might be a status Indian but he is also a Canadian citizen which means that is afforded the rights as part of the larger Canadian society.

The harm principle suggests that a person's liberty can only be interfered with when they are harming others. In this case, Thomas was directly harmed (physically and mentally) by the actions of the defendants. In this case, the harm principle would dictate that since the defendants have directly interfered with the rights of the plaintiff, then it is appropriate for the courts to step in and limit their liberty and to prevent them from inflicting further harm on others.

It is also appropriate to apply Mill's notion of 'no man is an island', meaning that no one is completely isolated and that their action may directly or indirectly impact other no matter how far removed they may seem. Although aboriginal people are distinct and sometimes live in isolated and remote areas, their actions still affect others. In this case, we can see that the defendants were members of the Cowichan Band who are carrying out a ritual unique to their band. In doing so, they have undoubtedly affected the rights of the plaintiff and have directly harmed the plaintiff who is a member of a completely separate aboriginal band.

While some of Mill's concepts can be portrayed in the current case, we believe that Mill would not extend some of these principles to aboriginal people. While some of Mill's ideas appear to be fair and justified, there is also an underlying tone of discrimination. It is likely that Mill would think that Aboriginal people are in a 'backwards' state of society and therefore it may be appropriate to interfere with their liberty or that they have no liberty to begin with.

In examining Mill's theory, we believe Mill would reach the same conclusion as the trial judge in that the defendants are at liberty to do as they please such as engaging in rituals distinct to their band until it harms another individual. While the court offers alternatives such as attaining consent to engage in the ritual, we believe that Mill would disagree with this alternative and suggest that it is never appropriate to "grab" someone and then proceed to directly inflict harm on them.

Mill would say that Thomas' choice to distance himself from Aboriginal culture is certainly within his right as an individual and is not harming anyone else. However, the aboriginal people who have "grabbed" Thomas would potentially argue that his action in separating himself is harming the collective rights of the community, something that Mill would likely argue against.

Paternalism, Gerald Dworkin

Dworkin seeks to reconcile the ideas of liberty and anti-paternalism with his own notion of paternalism. He argues that there is a significant range of cases where paternalistic interference with the liberty of individuals can be justified. For instance, where the purpose of interference is prevention of harm to that person; however, there may be incidental effects in which the prevent of harm extends to third parties. Such restrictions are justified when the consequences of individuals’ actions are far-reaching, potentially dangerous and irreversible to the person’s autonomy. Dworkin contends that we are not substituting our own judgment of what is good for another nor imposing our will upon that person contrary to his/her own values and will; rather we are acting to facilitate the pursuit of those values themselves.

Application to Thomas v Norris

Taking a Dworkian perspective on paternalism to the case, it could be argued that the defendants’ interference with Thomas’ individual liberty could be justified.

Thomas’ dissociation from Aboriginal culture could be seen as having the possibility of leading to irreversible harm when looked at through the lens of the collective rights of the aboriginal culture. It could be argued that in his rejection of the Spirit Dance, he is already causing harms to the collective through the rifts being brought to the collective. Thomas’ actions could be causing far-reaching consequences by introducing conceptions from a foreign system of values, which, through the outcome of the court decision, is evident in the fact that certain aspects of the Spirit Dance are now confirmed as illegal.

Law and Economics, Susan Dimock

Susan Dimock provides an account of law and economics. The ultimate goal of law and economics is to maximize utility. The purpose of law is to maximize social wealth. As such, good laws are those that are efficient to this end. Dimock discusses three economic models and how they each view efficiency. It is important to keep in mind two things. First, these models rely on the presumption that humans are rational and make decisions in their best interests. Second, wealth is not equivalent to just monetary wealth, it includes any measurable value.

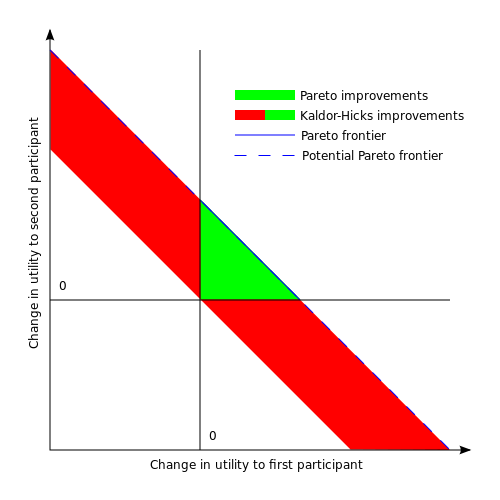

Pareto-Superiority

Pareto-superiority occurs when the latter state of affairs (S2) is better than the previous state of affairs (S1). A transaction between two parties, for example, will be pareto-superior when one person is better off in S2 compared to S1 and the other is no worse off in S2 than S1. This can occur in two ways. In win-win situations all parties benefit from the deal. In win-lose situations one party benefits while the other does not, but the winner fully compensates the loser while still maintaining some benefit. In both these scenarios we see an overall net gain – an increase in social wealth – which is efficient. As human beings are rational they will not choose a loss for which is not compensated, so voluntary market transactions will always be pareto-superior.

Kaldor-Hicks

Kaldor-Hicks can be seen as a response to some of the shortcomings of the pareto-superiority approach. In the Kaldor-Hicks approach S2 is efficient if and only if the winners could compensate the losers so that no one is worse off in S2 than in S1, and at least one person remains better off.

How is this different than pareto-superiority?

Pareto-superiority is only concerned with the people involved in the particular transaction. If it is a two person transaction then only those two people are considered when calculating net social wealth. Kaldor-Hicks, on the other hand, recognizes that third parties are impacted by these transactions. A two party transaction may impact many other people in a negative (or positive) way. Under the Kaldor Hicks model, any neighboring losses should be accounted for when we are looking at social wealth.

There is another important difference. In pareto-superiority the loser must be compensated, however, in Kaldor-Hicks, it is enough that the losers could be compensated. This in itself will maximize social wealth and is seen as efficient, despite no actual compensation being paid. Laws will promote efficiency when they require transaction parties to consider the losses of third parties (i.e. through property rights, regulation, etc.), and it may be efficient to require them to compensate these parties as well (i.e. through taxation, awarding damages, etc.), as long as social wealth is maximized.

A Judge's Role

The purpose of a judge is to pursue efficiency. The common law has developed to give judges considerable power to do this by creating and protecting rights, protecting transactions, and establishing procedural rules to increase efficiency. Dimock looks specifically at tort law, property law, contract law, and criminal law to explain how these (their common law roots) are based on efficiency and maximizing social wealth.

Of note, the economic approach doesn’t apply well to statutory law. Dimock explains that this is because legislators are quite often not pursuing efficiency, but have other goals in mind. Legislators want to get re-elected so it is not uncommon to pass legislation that helps a certain interest group while making things worse for many others. This outcome can be one that does not maximize social wealth at all.

Application to Thomas v Norris

At first glance, it would seem that on its face the law and economics approach has little to do with this case that involves aboriginal rights and individual rights. However, when we consider that it is a torts case it is easier to understand how economics plays a role. Tort law functions to compensate a victim for a harm caused by a wrongdoer.

When the spirit dance rituals were conducted it is clear that the plaintiff is worse off afterwards while the defendants are at minimum no worse off. Fast-forward to the decision of the case and the plaintiff is awarded damages while the defendants must pay them. From this stance there is little to show that net social wealth has been increased. It may be argued that the compensation the plaintiff receives does not outweigh the harm he suffered. Furthermore, the defendants are worse off than before they performed the ritual. But, such a view only looks at the two interacting parties and is framed from a Pareto-Superiority approach.

It is when we consider third parties, such as in the Kaldor Hicks model, that law and economics approach is more easily introduced. The outcome of Thomas v Norris favours the plaintiff. The judge finds that the practice of Spirit Dancing caused harm to the plaintiff. The decision finds that this type of harm to be unacceptable and fails to see aboriginal rights as a defensive shield to the act. The court demonstrates the importance of fundamental individual rights and indicates that abuse of such rights will result in the finding of damages for the plaintiff. Thomas v Norris pushes the deterrent features of tort law. This deterrence will see an overall increase in social net worth as it reduces the amount of harm caused to an individual that otherwise may have been allowed. The move from a situation where harm to an individual may be justified to one where it is not, even by aboriginal rights, is a positive move.

Dimock states that the purpose of a judge is to pursue economic efficiency by delivering judgments directed at maximize social wealth. Further, Dimock notes that rights are constructed and protected in the common law to increase efficiency. A law and economics approach recognizes the well-entrenched individual rights in tort law. Their rigorous protection will improve the social net wealth. From a law and economic perspective tort law has a two-fold effect by penalizing wrongful behavior and creating future deterrence for that behavior. It discourages possible wrongdoers and by doing so creates a situation where there are less negative drains on social wealth.

This approach may raise significant difficulties for aboriginal rights. Any infringement on an aboriginal right that maximizes overall social wealth would be justified. Aboriginals are a minority so such a situation may arise often. If this were to occur greater policy concerns may arise where Parliament seeking to recognize and protect Aboriginal rights would be undermined in pursuit of economic efficiency. The law and economics approach, admittedly, does not work well with statutory law. Law and economics proponents argue that this occurs because the motives of legislators are most often not directed at maximizing social wealth. For this reason the model prefers judge-made common law over legislation. This would result in an easy dismissal of aboriginal rights which is an important aspect of Canadian law.

Overall, the law and economics approach would come to the same conclusion as the judge. As aboriginal rights are granted by legislation, compared to the well-entrenched individual rights that are granted by the common law, the economic approach would almost certainly favour the latter. Even more so because aboriginals are a minority group whose social wealth could be disregarded in situations that increase the overall social wealth of Canada.

Feminist Theories, Catharine MacKinnon

There are two main ways in which feminism has been applied to law. In the first, scholars borrow from conventional legal fields various theoretical approaches and then applied these approaches towards gender issues in law. The second approach identifies legal doctrines that cross-cut conventional legal boundaries and then subsequently models alternative relationships between gender and law.

While there are a multitude of approaches that can be used to address the issue of gender in the law, there are several commonalities among feminist theories. All theories seek to promote the interests and equality of of women. This is done with recognition of patriarchy as the overarching system, which subordinates and exploits women. Feminists challenge the central tenants of law including: the neutrality of law; the ideal of the rule of law; the current model of judicial reasoning; the separation of law from politics; and the separation of law from morality. One of the key scholars is Catharine MacKinnon who has commented extensively on law as an expression of male power.

According to MacKinnon, "law is the site and cloak of force", which has been interpreted to make that the law is used to legitimize the use of force in liberal society. MacKinnon posits that the law makes male domination invisible and legitimate by adopting the “male point of view” and articulating it as both natural and right. Moreover, she suggests that law is a male creation and that there is really nothing to stop male domination as it appears natural. MacKinnon suggests that what what the law needs to do is to stop and prevent the continuous perpetuation of male dominance in society. To change this, two steps need to be taken; first, there needs to be a claim to correct women's concrete reality, and second there needs to be a recognition that male's power over women is through individual rights (vis a vis, pornography is protected because it relies on the freedom of expression).

MacKinnon is hostile towards liberal feminism and socialist feminism. In fact, she argues that such theories are not feminism at all. Liberal feminism subsumes women into the human category of individuals which obscures the gender hierarchy, while socialist feminism subsumes women into the marxist category of proletariat and obscures gender hierarchy. MacKinnon takes an entirely different approach that builds from the ground up. She advocates for "a one true feminism". Her approach differs from other models in the feminist school of thought in that it contradicts the desire to categorize and structure what it means to be a woman. Her approach is highly directed at taking into account the varying perspectives that are unique to the individual. MacKinnon pushes for the creation of a path wherein women might become "a sex for themselves".

In applying femnisism to the facts of the case it is useful to review two theories present in the feminist body of theorum.

Liberal Feminism

Liberal feminism argues for equal rights between the genders. According to this school of thought the solution to the oppression of women is to provide equal opportunity. Formal equality is advanced by liberal feminists in support for equal representation in political, educational, and economic spheres.

Post Modernist Feminism

Post modernist feminism is strongly rooted in anti-essentialism which opposes a common shared assumption about the rationality of law and the objectivity of truth. Post modern feminists object to a single ideal identity for women. Post modernists reject the notional methodology adopted in other theories which views women as a natural existing category, then assumes the removal of an oppressive regime will result in women achieving an equal status suggest. This model hints towards the existence of one absolute truth. Instead, Post modern feminists argue for the liberation of women in a two fold approach which recognizes social constraints and emphasizes the participation of women in finding their own construction.

Application to Thomas v Norris

Thomas v Norris raises a interesting set of issues when interpreted from a feminist approach. While the case itself is not directly related to gender issues, it shines light on the deep seeded structures within the judicial system that continue to subordinate and exploit women and their rights.Throughout the case the oppression of the patriarchal society is evident in it's attack on a historically disadvantaged group in society.

Taking a liberal feminist approach there are formal and informal blocks that have been created in society to place minority groups in a subordinate position and to impede their ability to succeed in public spheres. This subordination is reinforced in the decision as the right to practice spirit dancing is undermined and penalized.

From a post modernist feminist approach the decision showcases the continued dominance of patriarchal concepts and methods of interpretation. The most overt example of this is the promotion of an essentialist view of the individual held by the court. Post modernist feminists reject the essentialist approach of the reasonable person used by courts. They posit that this oversimplification favors the overarching institutions endorsed by patriarchy. A meta-theory is rejected by post modernists, as an individual’s experience of reality is more of a function of fluctuating constructed possibilities. The individual is molded by multiple institutional and ideological forces which ebb and flow, overlap and intersect and at times contradict each other. The judiciary makes no room for the unique experience of the individual. The perpetuation of this essentialist view of the individual is a construct of the existing patriarchal system. It’s protection within the judicial system continues to promote patriarchal values which perpetuate the exploitation of women. The continuation of an essentialist view undermines the experience of women.

In Thomas v Norris the court extends the use of an essentialist view towards undermining the experience of the individual. The decision demonstrates that the recognition of an Aboriginal right is given only when it meets the established checklist of the dominant system. Throughout the judgment the court fails to consider significant parts of the defendant’s argument. There is little emphasis given to the unique reality of the individual. There is little to no credence given to the true rights of the individual but rather the individual that the patriarchal society chooses to promote for its own purposes.

Throughout the decision Justice Hood overtly exemplifies these constructs in his judgment. He states:

“The assumed aboriginal right, which I perceive to be more a freedom than a right, is not absolute and the Supreme Court of Canada reaffirmed this in Sparrow. Like most freedoms or rights it is, and must be, limited by laws, both civil and criminal, which protect those who may be injured by the exercise of that practise... it seems to me that in determining the nature and scope of the right protected, reference must be made to both the criminal and civil laws which govern the relationships between Canadian citizens in a peaceful society in order to protect the freedoms and rights of all.”

A post modernist feminist may reject the outcome of the case, not only for it’s decision but in contesting the court’s authority and approach. While a post modernist feminist may support protecting the security of the person they would prefer to see that right upheld as an outcome of a different form of analysis. The ideal framework would recognize, accept, validate and promote the individual experience as the central focus of the judiciary. Instead, the case adopts an approach of comparing the facts against the established definitions as set out by the patriarchal system.

A post modern feminist would likely embrace the development of an aboriginal court that is better attune to addressing aboriginal issues, which would place higher value in understanding the unique perspectives of the individuals within that society. A post modern feminist would support an aboriginal court that was position towards having a closer connection and understanding of the various constructs that create an individual. Such an approach would be a marked departure from the existing patriarchal judiciary.

A different aspect of feminism is the focus on the lived experiences of men and women. In this case, feminism would be concerned with the experiences of all the actors in the case including the plaintiff, defendants, and people external to them such as the judge, and Kim Thomas (Mr. Thomas’ wife). Previous, theorists have posited an universalist idea of human nature which is refuted by feminism. Feminism considers the world to be constructed based on patriarchy and this is replicated throughout society. In the case, Kim Thomas is the motivation behind Mr. Thomas being “grabbed”. She was the person who approached the elders to “grab” Mr. Thomas, she was also ultimately the person who gave consent to initiating the Spirit Dance. However, in the judgement her part of the act is sidelined and the members of the Spirit Dance and Mr. Thomas (who are all men) become the central focus on the issue. From a feminist perspective Kim’s role in the “grabbing” should be emphasized. Her lived experience would be considered to be important.

Critical Legal Studies / Critical Race Theory

Critical Legal Studies

Critical Legal Studies (CLS) is a body of thought that developed in the 1960s and 1970s in the United States that takes a critical look at what it sees as many assumptions inherent but not commonly acknowledged that are present in the legal system. Adherents of CLS are referred to as “Crits”. Sharing aspects of both legal realism and nihilism, CLS skeptically postulates that as a society we have collectively given inherent value to fictional manifestations used to deny that which is difficult to reconcile with what we believe our culture should encompass. Specifically, the movement criticizes the internalization of rational explanation for why our capitalist society does not accord with our ideas of equality and freedom.

The term “hegemonic consciousness” is used by Crits to describe the collective set of beliefs that come to be thought of as common sense due to their prevalent use and continual reinforcement. It is theorized that our legal system is a form of hegemonic consciousness that has become reified through use and perpetuation. Reification is the giving of inherent value to that which is arbitrary and subjective. Crits do not believe that there is anything inherently objective in our legal system and promote the idea that the reified assumptions are a form of rectifying (and denying) the disagreement between the perceived virtues in our legal system, such as equality and freedom, and the capitalist values that perpetuate oppression and maintain the hierarchical order of our society. It is likely that Crits would speculate that Dworkin’s “principles” were nothing more than reified theories that served to perpetuate the order of the existing class system, with the evolution of principles being nothing more than slight alterations reflecting minor changes to the dominant group in society.

In fact, the Crits would criticize any meta-theory that claimed to ascribe a common set of values or morals to all of humanity as simply a manifestation of the current hegemonic consciousness as manifest by the dominant class in society. Even the idea of what is a “valid” law would likely be questioned by the Crits as simply having been defined by the dominant consciousness.

While Crits share the idea with legal realists that legal outcomes are predetermined by judges, they differ in that they do not believe that a less biased approach to the existing system would produce an objective system. They believe that the entirety of our law serves to reproduce the oppressive character of society in that at its very root are arbitrary political concepts that perpetuate the social order.

The common law of torts is said to encompass our fundamental notions of justice. However, as Duncan Kennedy has pointed out, inherent in how this law is structured is a system that promotes certain outcomes and has the effect of framing relations between classes in a way that is an arbitrary construct that reinforces our “hegemonic consciousness”.

CLS has generally been a deconstructivist movement that in theory holds out the existence of a meta-system that could garner popular support and eliminate the oppressive elements of our legal system. However, the Crits have largely splintered into various groups, including the Critical Race Theorists and the Feminist Legal Theorists, who do not believe that any one system of laws could effectively address the needs of the various groups in our society.

Application to the Case

Critical Legal Studies (CLS) is similar to feminism in postulating that there is no unified theory to explain human nature. While, not strictly speaking a theory it is a lens that considers the political nature of the legal decision and considers the law and legal analyses to be based in a political structure. The distinction between law and political cannot me made CLS claim. Justice Hood does not explicitly comment on the political ramification of his decision, however, CLS scholars would contend that he is rendering his decision in light of a particular political landscape. Thus, Justice Hood’s detailed logical analysis in considering whether an Aboriginal right should be recognized is crouched in a political structure that undervalues and refuses to recognize collective Aboriginal rights.

There is no neutral person in CLS. This is in direct contrast to Dworkin who saw the individual as a neutral figure with rights to who the law is being applied. Therefore, CLS would contend that the myth of the neutral figure is perpetuated in the judgement when Justice Hood assets that Mr. Thomas’ generalized rights as a Canadian citizen are immutable and cannot be interfered with by Aboriginal collective rights. In approach to individual rights in the case can also be criticized by CLS as being a reified concept.

Reification occurs when abstract things become material. The whole notion of individual rights has been reified such that the law (and the judge who truly believes) views it as something fundamental that has an inherent value akin to stating that the sky is blue. In reality, the very existence of aboriginal laws and values that hold collective rights as being able to trump individual rights in certain conditions negates this premise, but as a society we are conditioned to the common consciousness that we see other conceptions of rights as inferior and they are therefore dismissed or relegated to a “right” that is valid only if it doesn’t conflict with our reified rights.