TRU/Law3020/GroupS

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Vancouver Rape Relief Society v Nixon, 2005 BCCA 601

- 3 Points of Analysis

- 4 Natural Law Theory: Thomas Aquinas

- 5 Legal Positivism

- 6 The Separation Thesis: HLA Hart

- 7 The Morality of Law: Lon Fuller

- 8 Law, Principles and Rights: Ronald Dworkin

- 9 Liberty and a Response of Paternalism: John Stuart Mill

- 10 Law and Economics: Law as Efficiency

- 11 Feminism

- 12 Critical Legal Theory

Introduction

Group S is comprised of Richard Steed, Cornelius Suen, Blake Tancock, and Kerem Tirmandi. This WikiEducator page provides an in depth analysis of the controversial decision in the 2005 British Columbia Case,Vancouver Rape Relief Society v Nixon.

Vancouver Rape Relief Society v Nixon, 2005 BCCA 601

Facts

Vancouver Rape Relief Society v Nixon (Rape Relief) is a British Columbia Court of Appeal decision that addresses the issue of discrimination on the basis of biological sex.

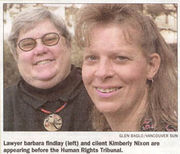

Kimberly Nixon is a postoperative male-to-female transsexual. Ms. Nixon realized at a young age that her "physical maleness did not accord with her own sense of herself as she believed she was a female".

The Vancouver Rape Relief Society (The Society) is self-described as a “non profit feminist organization whose mandate is to provide services to women victims of male violence and to fight violence against women”. Ms. Nixon, reflecting on her own history of abuse , wanted to help other women, and applied to work at Vancouver Rape Relief as a counsellor.

However, on discovering that Ms. Nixon was born male, Rape Relief Society deemed her an unacceptable candidate for the position. The Society's view is that "a woman had to be oppressed since birth to be a volunteer at Rape Relief and that because she [Ms. Nixon] had lived as a man she could not participate".Ms. Nixon’s contends that by rejecting her on the basis of her biological sex Rape Relief was being discriminatory.

In response, The Society contends that all those offering peer counselling on behalf of the Society, must share the experience of being born and raised a female, thus ruling Ms. Nixon out as a candidate. They argue that only biologically-born women can truly understand the experience of being female.

In deeming Ms. Nixon an unacceptable candidate The Society contravened ss. 8 and 13 of the Human Rights Code, however they relied on s. 41

Applicable Law

There are Three Key Provisions in the Human Rights Code that apply to this case ss. 8, 13, and 41.

In Rape Relief the appellants were accused of breaching ss. 8 and 13 of the Human Rights Code:

8(1) A person must not, without a bona fide and reasonable justification,

- (a) deny to a person or class of persons any accommodation, service or facility customarily available to the public, or

- (b) discriminate against a person or class of persons regarding any accommodation, service or facility customarily available to the public because of the race, colour, ancestry, place of origin, religion, marital status, family status, physical or mental disability, sex or sexual orientation of that person or class of persons.

13(1) A person must not

- (a) refuse to employ or refuse to continue to employ a person, or

- (b) discriminate against a person regarding employment or any term or condition of employment

In deeming Ms. Nixon an unacceptable candidate The Society relied on s. 41 of the Human Rights Code, which states:

41 If a charitable, philanthropic, educational, fraternal, religious or social organization or corporation that is not operated for profit has as a primary purpose the promotion of the interests and welfare of an identifiable group or class of persons characterized by a physical or mental disability or by a common race, religion, age, sex, marital status, political belief, colour, ancestry or place of origin, that organization or corporation must not be considered to be contravening this Code because it is granting a preference to members of the identifiable group or class of persons.

Further, the Human Rights Code lays out specific conditions which must be met by any organization relying on s.41:

- (1) must, as its primary purpose, have the promotion of the interests and welfare of an identifiable group of persons characterized by a common ground of prohibition under the Code;

- Primary purpose: Provide services to the victims of rape

- (2) establish a connection between the ground of discrimination and a primary purpose of the organization; and

- Connection between ground of discrimination and a primary purpose of the organization: Women raised from birth had those unique experiences and could aid rape relief victims in the proper way (this bettered the objective of the Society)

- (3) justify the exclusion in an objective sense by the particular nature of the organization.

- Justify the exclusion: Discrimination was done in good faith because they believed that the interests of their identifiable group would be better served by having volunteers be women from birth.

Courts Decision

The initial Human Rights Tribunal found that the Society had discriminated against Ms. Nixon.

However, the British Columbia Court of Appeal ruled that there was no discrimination. The British Columbia Court of Appeal concluded that section 41 of the Human Rights code affords not-for-profit organizations an internal preference to a sub-group of whose interests it was created to serve. In other words, The Society could give preference to women because it was created to serve women. Likewise it could reject those who fell outside the group served. However, it must be done in good faith and there must be a rational connection between the preference and the entity's work, or purpose.

The Society was not required to establish that its primary purpose was to promote the interests of women who have lived their entire lives as females in order to benefit from s. 41. The Society was entitled to exercise an internal preference in the group served, to prefer to train women who had never been treated as anything but female.

Points of Analysis

Through the application of various historical legal perspectives the following two points will be assessed:

- The Courts decision to afford The Society the right to discriminate, and

- The law applied under the Human Rights Code, specifically, ss. 8,13 and 41.

Natural Law Theory: Thomas Aquinas

When assessing the decision reached by the courts through the eyes of Thomas Aquinas and the Natural Law Theory four questions need to be asked to determine whether or not the law applied was valid:

- Was the Law directed to the common good?

- Was the Law made by a valid Law Maker?

- Does the Law follow Practical Reason?

- Was the law promulgated?

1. Was the Law directed to the common good?

Two members of our group expressed different views with regard to how the common good was being fulfilled in Rape Relief. The first point of view argues that the ruling in Rape Relief went against the common good because they were discriminating against individuals that were attempting to contribute to the Society and in turn the "common good" of the public.The second perspective held that the common good was preserved in this case by adhering to the statute and that the legislative will constitutes common good.

“Ms. Nixon Volunteering qualifies as Common Good”

The Natural law theorists believe that the good of the community is paramount to the good of a specific individual or even a group of individuals. According to Thomas Aquinas and the Natural law, Ms. Nixon's male-to-female transformation would be irrelevant in comparison to her ability to contribute to the common good through volunteering at the Society.

The Rape Relief Society's goal is to provide a service that mitigates a social problem. If Ms. Nixon had the ability to contribute to this service then a Natural law theorist may reject the ruling in this case on the basis that the common good is not being served and thus this law is invalid.

2. Was the Law made by a valid Lawmaker?

“Legislative Will Constitutes The Common Good”

Aquinas believed in a supreme lawmaker whose authority on earth represented God's will. In Vancouver Rape Relief v. Nixon the judge's ruling hinged on an interpretation of section 41 of the Human Rights Code - a piece of legislation drafted by a supreme governing authority. The question that must be asked then is, did the judges ruling reflect the legislative will – which according to Aquinas is the common good of the public?

To Aquinas the role of the judiciary is simply to apply the law. True authority rests in the greater wisdom of legislators, and only when legislation runs contrary to a natural right and would produce an unjust outcome should the judge deviate from the written code.

In Vancouver Rape Relief the judge took a "broad, liberal, and purposive" approach to interpretation. The aim of this approach is to reach an outcome that "advances the broad policy considerations" that underline human rights legislation. While this could be interpreted as an over-extension of judicial authority, it more likely implies that the approach should be in line with the will of the legislature.

At the same time, the judge further states that this approach does not give a court license to "ignore the words of the Act in order to prevent discrimination wherever it is found." In one sense this reinforces a tenet of Aquinas' natural law by suggesting the judge cannot deviate from the will of the legislature, and at the same clashes with another tenet - that the judiciary should strive to reach a just outcome above all else and even when it runs contrary to the legislative will.

In this case the court ruled against Nixon, by arguing that section 41 afforded particular groups (charitable, philanthropic, educational, fraternal, religious, among others) an "internal preference" in the group served. This could be viewed as enforcing discriminatory polices and is therefore unjust or against the common good. At the same time, when looking into the rationale behind the decision it is clear that Justice Saunder's has the common good at mind.

Saunders notes that, "to force people, especially those in an organization such as the respondent, which has its own radical agenda, to associate with those who for some reason deeply offend their own avowed principles, can lead not to acceptance or at least toleration, but, if not to hatred, at least to animosity." In other words, forcing people to embrace individuals who deeply offend their own avowed principles is corrosive to the social fabric that binds us together and with it the common good as well. That this ruling was reached by interpreting a statute, further suggests that Aquinas would more likely view this as adhering to the legislative will, which in turn is upholding the common good.

3. Does the Law follow Practical Reason?

In Rape Relief the laws in question are ss. 8(1),13(1), and s. 41 of the Human Rights Code. The Human Rights Code was enacted to prohibit discrimination in society.

The language in s. 8(1) and s 13(1)(a, b) of the Human Rights code prohibits discrimination based on certain standards for employment and public services. However, s. 41 of the Human Rights Code grants certain organizations an "internal preference" or an exemption from some of the provisions regarding discrimination. To not be considered as contravening ss. 8 or 13. Aquinas would likely hold that the laws involved in Rape Relief follow practical reason because s. 8 and s. 13 are umbrella provisions legislated to achieve the common good, while s. 41 allows for “practical” discrimination by certain organizations where appropriate and also in the interests of maintaining the common good.

4. Was the law promulgated?

To Natural Law theorists, the purpose of law is to compel obedience. In turn obedience of the law will result in the common good. For this to occur, the law needs to be knowable. To Aquinas, people cannot obey laws that they do not know, and for law to be knowable it must be written.

The law in question in Rape Relief is the Human Rights Code. The Human Rights Code is codified and accordingly knowable.

Morality and the Natural Law: Natural Law theorists posit that the law is derived from a divine source and is therefore innately morale. In the context of Rape Relief, this would mean that the the Human Rights Code is derived from the will of a divine power which in turn is reflected through the will of the legislature and put forth with the purpose of promoting the common good.

Legal Positivism

This section provides an analysis of legal positivism and an application of legal positivist theory to Rape Relief.

Legal Positivists believe that laws may have moral content, however, (and in contrast to Natural Law theory), morality is neither innate nor necessary to law.

This section will proceed by analyzing and applying the views of John Austin, HLA Hart, Jeremy Bentham, and Joseph Raz.

John Austin

For John Austin, a valid law, "must be a command issued by superiors to subordinates and backed by sanctions".

Unlike Aquinas, Austin does not hold that citizens are morally obligated to follow all Law. Rather, Austin believes only “valid” law imposes a moral obligation upon citizens of the State.

For Austin, a valid law must be a command, issued by superiors to subordinates, and backed by sanctions. Austin considered "the sovereign" to be a determinate and common superior.

He categorizes laws into three categories:

- Gods Law

- Positive Morality (Norms/policy/custom)

- Positive Law

HLA Hart

In Hart's view of legal positivism, authority is derived from custom, meaning “the law is only valid when it is actually enforced by officials and practice and recognized by society”.

Hart structures laws Into primary and secondary rules. Primary rules impose positive and negative duties on citizens. Secondary rules confer power to the legislature and judiciary. Furthermore, they provide a framework through which laws are discovered and can be adapted.

These primary and secondary rules are promulgated through the Rule of Recognition. The Rule of Recognition is founded on conventions through which officials accept and abide by certain criteria of standards that provide guidelines and govern their actions.

Jeremy Bentham

Bentham held that the Law should not be built on a foundation of morality. Rather, Law should be founded on the principles of utilitarianism: the belief that law is right if it is useful and of benefit to the majority of society, or in other words the greatest good for the greatest number of people.

Accordingly, rather than asking if a law is moral, Bentham would ask, “does the law maximize utility?”

Joseph Raz

Raz views Law as the ultimate authority.

As such the Law holds the right to tell subjects what they can and cannot do. Citizens of the state are not invited to discuss if the reasons underlying the laws are good, sound or sensible.

Although Raz viewed Law as the ultimate authority, he still believed a question must be asked; “is the law justified and does this law confer a benefit on society?”

Application of Legal Positivism to Rape Relief

The Human Rights Code provisions considered in Rape Relief would be viewed by Austin as positive law because it fulfills the necessary criteria: it is a command issued by superiors to subordinates and is backed by sanctions. The code was enacted by Parliament, which Austin would view as the sovereign, and is directed to the public for the preservation of the public's human rights.

The code itself provides sanctions for provision violations. Furthermore, according to Austin, laws must be created according to the law-making rules of the jurisdiction, which has been done in this case.

Contrary to Austin, Mills would likely point out that no governing body in Canada is absolutely above the law, and thus, the law was not passed by a true “sovereign”. In response, Austin would likely note that the legislation is based the will of the parliament, who are authorized, through s. 33(1) of the Charter, to pass a law which will operate “notwithstanding a provision” within the Charter. Through s. 33 of the Charter, Austin would likely consider Parliament to be the sovereign in Canadian jurisprudence.

In direct contrast to the positivist tradition, Postmodern Feminists would likely point out that Harts application would be classified as a “Grand Theory”, and thus, fail to take into account the individual circumstances of the case. The absolute application of established law disregards case specific facts and fails to provide individual solutions to, in this case, both women and Nixon.

A complication with Austin's brand of legal positivism is that it is legislation centric. Judicial decisions are simply specific commands as opposed to the generalized rules contained in legislation. The judge's ruling in this case was in accordance with the legislation and consisted of him pointing out the exception contained within the provisions of the code.

In considering the role of the Judiciary, Fuller would be quick to point out that the role of the Judge requires much more than simply applying established law.

Hart would likely view the Human Rights Code as representing a primary rule. The Human Rights Code provides for (among other things) a set of guidelines that dictate what society can and cannot do with respect to hiring practices.

Hart would likely view how the court can interpret and should interpret the Human Rights Code to reach an outcome as a manifestation of the will of the law. This would be seen as Hart as a secondary rule.

Justice Saunders states that the "courts approach human rights legislation using a broad, liberal and purposive approach to "advance the broad policy considerations underlying it", to interpret the provisions "in a manner befitting the special nature of the legislation", giving it "such fair, large and liberal interpretation as will best ensure the attainment of their objects.""

This is a reflection of Hart's rule of recognition.

Here, Justice Saunders’ interpretation is governed by an accepted and practiced principle that Human Rights legislation should be interpreted liberally. Further, in reaching her judgment, Justice Saunders analyzed previous cases addressing the same issue to better understand what the law is and how the law should be enforced.

Unlike Hart who would recognize Justice Saunders’ “liberal and broad interpretation” of the law as a “judicial requirement”, Aquinas would likely argue that the law is derived from a higher non-human source and is meant to be applied strictly with little deviation.

Further, Austin would point out that no one, except for the sovereign, is truly above the law. Austin would likely argue that in her “broad and liberal” interpretation of a law passed by parliament, Justice Saunders was stepping outside her role.

Bentham would likely employ a cost benefit analysis in assessing whether or not the provisions within the Human Rights Code, which led the Courts to their decisions, ultimately maximized utility.

In taking this view Bentham would likely hold that the provisions were successful in maximizing social utility.

The Human Rights Code is aimed at ensuring minority groups are not discriminated against with regards to employment opportunities. However, non-for-profits, such as Rape Relief, who are aimed at helping a specific disadvantaged group are permitted to practice discrimination in hiring. The Human Rights Code allows this so that the disadvantaged group, such as women recovering from physical abuse, are not forced into rehabilitation centres which are staffed by men.

In the totality of the circumstances it is likely Bentham would see the Human Rights Code as maximizing social utility. Further, he would likely agree with the judgment and view it as re-enforcing the goal of the legislation.

Much like Bentham in this case, Raz would view the Human Rights Code as a justified law which confers a benefit on society.

Raz would likely argue that, in preventing absolute discrimination in the hiring process, while enabling non-for-profits to practice a discriminatory hiring process, in and of itself confers a benefit on society. Further, the positive aspect of both prohibiting discrimination and protecting weak and disadvantaged groups would likely, in the eyes of Raz justify the law.

The Separation Thesis: HLA Hart

HLA Hart's separation thesis is founded on the principle that the existence of law is not contingent on morality. That is, and although they may frequently run parallel, there is no necessary connection between the two. He states this in the terms of what is (in other words the law) and what ought to be (a moral law). That the law is not inherently moral, allows us to evaluate, critique, overrule, and adapt it. Furthermore, this flexibility affords us with the means to best ensure that our laws come to reflect our conception of morality.

In Rape Relief we have a case in which one conception of morality runs directly contradictory to the law as it stands. Justice Saunders ruled that though the hiring practices of Vancouver Rape Relief with respect to the transgender woman was indeed discriminatory, the law nevertheless affords certain organizations the right to discriminate in their hiring practices when the hiring of such personnel would violate the fundamental beliefs of that group.

There is no doubt that the law and the ruling stand in direct contradiction to Ms. Nixon's conception of morality. At the same time, there is no doubt that the law and ruling were in line with the organizations conception of morality. That we have two mutually antagonistic conceptions of morality, demonstrates the fundamental issue of a morally-entrenched law and why - according to Hart - they should and indeed are separate: the impossibility of reflecting both our collective and individual conceptions of what ought to be.

Hart's Penumbra and Critisisms

Hart believes that legal rules are expressed in general terms. There is no legislation that applies specifically to person X, but laws will apply to a group of people or society as a whole. Hart states that all laws will have a "settled core of meaning" and this is where the idea of the Penumbra appears. The penumbra exists when a factual situation presented in a case falls outside of the settled core of meaning of the law.

Hart would view the Vancouver Rape Relief Society v. Nixon as an excellent example of a penumbra case. This case focuses on whether section 41 of the Human Rights Code, which allows for discriminatory selection of volunteers would fall outside the scope of the core of Human Rights code. The Human Rights Code is a law that exists to ensure that the rights of individuals are protected from unjust and discriminatory treatment. However s. 41 is an exemption clause in the Human Rights Code that protects specific groups right to freedom, expression, and security. In Rape Relief v. Nixon the divergence of the Human Rights exemption provision from the Human Right Code illustrates Hart's idea of the penumbra - and is a good example of where factual situations have fallen outside the settled core of a law.

Fuller disagrees and criticizes Hart's concept of the "core" and "penumbra" and in particular judicial interpretation. Fuller says there is no core of settled meaning and therefore can be no penumbra. He basis this on the fact that judges interpret the law in such a way that they are making it consistent with the purpose of law. He goes on to state that the "hard cases" or the penumbra cases as Hart would say are those where the purpose is uncertain or competing purposes are at play. Fuller would agree with the judicial decision in Rape Relief because he would say that the statute is precedent and in the context of this case the good it is trying to accomplish is the protection of private group rights.

Dworkin also rejects Hart's theory of the penumbra. Dworkin contends that that even where the rules do not decisively decide the issue (what Hart would describe as the penumbra scenario) principles and logical reasoning will provide the right answer. In Rape Relief, Dworkin would say that as long as the judges applied the proper principles and logical reasoning, the judgment they came to would be the correct outcome to the legal issue.

The Morality of Law: Lon Fuller

Fuller vs Hart's Separation Thesis

Hart separation thesis puts forth that law and morality are necessarily separate. For Hart, morality is subjective and ambiguous and therefore provides a weak foundation. Furthermore, if we believe the law is fundamentally moral it becomes impossible to critique it without also criticizing the moral grounding on which it is based.

Fuller rejects Hart's strict separation of law and morality.

Inner Morality

Fuller posits that laws derive their validity from an "internal morality". By this Fuller is not referring to a sort of god-given morality in line with the Natural law conceptualization.

Rather, Fuller refers to an inner logic through which valid laws attain their objective goodness. This logic is what distinguishes moral laws from the immoral.

Immoral law is not immoral law because of its evil ends, but because it lacks the inner and objective logic which makes a law moral. This, Fuller puts forth, is what is fundamentally wrong with Hart's conceptualization of the law: "(it) assumes evil aims have as much coherence and inner logic as good ones ... when men are compelled to explain and justify their decisions, the effect will be to pull those Moral Foundations of a Legal Order."

Rape Relief provides an analysis of the Human Rights Code's provisions on discriminatory hiring practices. The Code is inherently moral insofar as it aspires to prevent discrimination an innate and objectively real evil. The Code however affords certain organizations the right to be discriminatory in their hiring practices when the hiring of such personnel would violate the fundamental beliefs of that group. This exception demonstrates the inner logic of the Code. That discriminatory practices are inherently wrong is of course true. But to force certain groups to hire individuals when doing so stands in direct contradiction to their acceptable cultural values is also wrong, and more importantly, counterintuitive. To do so, would not only burden such groups, but create animosity and resentment, outcomes that run counter to the overall purpose of the act and the interests of society.

Law, Principles and Rights: Ronald Dworkin

Principles, Rules, and Policy

For Dworkin, the law is founded on rules, principles and policies. Rules are the fundamentalblack-letter law that are supported by principles and policies.

The rules in the Rape Relief are contained within theHuman Rights Code. The sections that are of importance are ss.8, 13 and 41. Dworkin would see these provisions as the black-letter laws which dictate how society carries on.

Policy and Principle

Dworkin dis between arguments of policy and principle. Policy arguments justify a political decision by showing that the decision advances or protects some collective goal of the community as a whole. Principle arguments justify a political decision by showing that the decision respects or secures some individual or group right. Dworkin holds that judicial decisions should be directed by principle in that they advance or protect an individual or a group right, which we see occur in Rape Relief. Policy decisions should be left to the legislature, a body that is far better equipped to be representative of the social body’s interests. Thus, the judiciary needs to offer the legislature a degree of deference and should only allow their decisions to be directed by principle.

Justice Saunders took a “broad, liberal, and purposive approach ... to advance the broad policy considerations underlying” the Human Rights Code, showing the legislature deference and enlarging the scope of the provision to ensure the Judiciary honours the legislature’s policy goals. Justice Saunders can found the legislature’s policy objective in the drafting of these provisions of the Human Rights Code: it is a document to preserve the human rights of the collective.

Justice Southin, in her concurring judgment, states that the freedom of association should also include the freedom from association. If Justice Saunders were to rule in favour of Nixon it would be denying Rape Relief the freedom to associate with whomever they wanted, and thus, work against the policy objective the legislature was pursuing when it drafted the Human Rights Code.

Justice Saunders writes that “to force people, especially those in an organization such as the respondent, which has its own radical agenda, to associate with those who for some reason deeply offend their own avowed principles, can lead not to acceptance or at least toleration, but, if not to hatred, at least to animosity.” Justice Saunders interprets the freedom of association to also include the freedom of disassociation, and maintains the policy objectives of the legislature, making a principle judgment that confers rights onto an individual or specific group. Dworkin would agree with her judgment.

Dworkin's Rights Thesis

Justice Saunder’s judgment can also be analyzed under the lens of Dworkin’s Rights Thesis.

Dworkin's Rights Thesis states that judicial decisions enforce existing political rights. Judges are to apply the law that other institutions make and should not make new law.

Justice Saunder’s effectively discharges the capacity of her station by showing deference to the legislation and upholding their policy goals. While applying previous law is the stated purpose of the judiciary, Dworkin acknowledges that this is not fully realized. Dworkin believes Judges often explicitly or implicitly make new laws for novel issues.

In this case however, Justice Saunders applies the law as it was drafted by the legislature and does not create new law. She relied on the decision in Caldwell et al. v. Stuart et al., which acknowledges the right of certain groups to discriminate in order to promote the interests of the specific class of persons that the group has committed itself to. Thus, Justice Saunders is deferential to the legislation that the legislature has enacted, and uses precedent to make her ruling of principle.

Rights: A Product of History and Morality

Dworkin holds rights are political because they are the product of history and morality; “what an individual is entitled to have in civil society depends on the practice and justice of its political institutions.” This is apparent in Rape Relief.

Nixon’s rights are subject to the practice and justice of the legislature, which has made a policy decision that justifies her discrimination in this one, specific instance. Judges must make fresh judgments about the rights of parties who come before them, but these political rights reflect political decisions of the past.

It is important to keep in mind that institutional history should not be a constraint on the work of judges but should act as an ingredient of the judge’s decisions. Institutional history is part of the background that any plausible judgment about the rights of an individual must accommodate. Political rights are a product of both history and morality.

Mill would disagree with Dworkin and say that liberty trumps deference. Although Dworkin would agree with Justice Saunders deference to the legislature’s policy objectives, Mill would argue that Nixon’s personal liberty is paramount, and thus, she has a right to volunteer with Rape Relief. Mill would likely state that deference to the legislature is not a sufficient limitation on her personal liberty

Aquinas would also agree with Dworkin. He would likely argue that the common good was preserved by Justice Saunder’s. Aquinas would also agree with Dworkin’s stance on the judge’s role. Aquinas believes that the legislative will constitutes the common good and that judges in their rulings must represent the legislative will. Dworkin believes this to an extent, in the sense that judges rulings are directed by principle instead of policy, which is the legislature’s territory.

Role of Judges

Dworkin believes that legislation and law is just words on a page, and it is the work of the judges to adjudicate and draw on general principles of justice and fairness. The leading case on allowing discrimination for specialized group is Caldwell et al v. Stuart et al [1984]. Rape Relief Society v. Nixon followed suit in a similar judgment and upheld that Rape Relief Society could discriminate for a identifiable group. Dworkin would view the Rape Relief Society judgment as following binding principles (precedent) in an appropriate fashion. Dworkin would perceive J. Saunders ruling as adhering to the idea that legal interpretation is like a "chain novel" - where there is some rigidity from what has come before, but also allows for a non static development of the law. In Rape Relief Society v. Nixon J. Saunders articulated the need to respect specialized societies and their freedom of choice. Saunders ruling was administered in a Dworkian fashion; Saunders reviewed how the Human Rights Code had been treated in precedent setting cases and then weighed the present principles and policies with the rules of his case to form a judgment that, as Dworkin would say was - "The Right Answer".

In contrast to Dworkin, Fuller believed that judges have a fidelity to the law. He stated that It was the role of the judges to interpret laws in a way that is consistent with the fundamental characteristics of the legal system. Fuller alluded to the fact that judges have a sacred function and primary obligation. In Rape Relief Society v. Nixon, Fuller would expect justice Saunders to fully develop and interpret the law. Fuller believed that when judges interpret the law, they give a certain type of meaning to the external morality as well as the inner morality of the law.

In Rape Relief, Fuller would likely be a true advocate of Justice Saunders persistence to probe into the "moral core" of the Human rights Code and the s. 41 exemption clause. Fuller would likely approve of the justification for Saunders judgement because Saunders made a conscious effort to pressure the issue and fully develop the law. Justice Saunders ensured that he reviewed analogous cases, evaluated the law in its circumstance and finally made an appropriate interpretation of s. 41 that referred to the external morality as well as the inner morality of the law.

Hart states that judges look to the "rule governed practices" - The Law and apply these rules when exercising discretion. Hart believes that these legislative and common law rules are expressed in general terms (core meaning) and so must apply generally. Hart would view Rape Relief as a penumbra case where the facts would fall outside of the core meaning of the law. Hart would says that if J. Saunders applied the proper ruled governed practices to the Rape Relief case all he would be doing is filling in the gaps outside the settled core of the law and he would likley arrive at the proper judgement.

Liberty and a Response of Paternalism: John Stuart Mill

Liberty

Liberty in Mill's philosophy of law concerns when and to what extent the law should interfere with our private choices as autonomous beings. It asks under what circumstances can restrictions be justified. Mill posits that a restriction on individual liberty is only justifiable when it is in the interest of preventing serious harm to others. This stands in contrast to a paternalistic view of the law which advocates restrictions on autonomy not simply in the interest of preventing harm to others but in the interest of preventing harm to the individual engaged in the harmful behaviour as well.

Paternalism

John Stuart Mill (Mill) believes that liberty is paramount. Mill holds liberty cannot be swayed, unless it is in the name of preventing harm to the individual or to society. This properly demonstrates the limits of liberty.

There is an exception to the liberty principle: it only applies to persons in possession of mature faculties.

Further, Mill believes that the concept of the tyranny of the majority may be dangerous to the individual: this idea states that the values of the most dominant class of society is so far above those of the minority that it justifies oppression of that individual or minority groups rights. He believes that there is justification for the proper limit restriction on individual liberty in the concepts of paternalism, legal moralism, and the offence principle. All of these things can be tied into Rape Relief and show how Justice Saunders came to her conclusion and how Mills himself may disagree with her judgment nonetheless.

Application of the Liberty Principle

Mill holds liberty of the individual is paramount.

There are two parties in this case whose liberties need to be balanced: Nixon’s andthe Society's. Nixon believed her liberty entitled her to volunteer and The Society believed their liberty entitled them to their own employment standards.

Justice Saunders ruled with the welfare of society in mind, thereby exercising a justifiable limit on Nixon’s liberty through the concept of legal moralism. Justice Saunders reasoned that in order to prevent social tension, Nixon’s liberty would have to be restricted because if Rape Relief’s liberty was to be restricted, it would amount to the government forcing organizations to employ people against their will and breed animosity and tensions that would harm society. Millwarns that the tyranny of the majority may danger the liberty of individuals.

The provision, s.41 of the Human Rights Code, may be viewed as the “tyranny of the majority”. S. 41 is likely to be viewed as the majority attempting to project their dominant values and views onto Nixon and to infringe on her personal liberty. Mills states that there is a limit to how far individual liberty can be infringed upon and states that the finding of this limit is of the utmost importance.

Truly, the main dialogue that we see at play in this case in regards to the restriction on individual liberty is between the liberty principle and legal moralism; Should Nixon have the liberty to volunteer wherever she wants?

Mill would disagree with the judgment of this case based on his liberty principle. He would have believed that Nixon’s liberty to volunteer should have been recognized, because her doing so would not undermine societal or communal values, but rather, advance them.

In coming to this reasoning Mill would likely consider society’s interest in having relief shelters and to have experienced individuals manning those shelters. Experienced individuals would provide the women with counsel that allows them to feel cared for and most of all, understood.

Nixon felt that her life experiences would be valuable in a counsellor capacity, since she was also the victim of abuse, and wanted to work for Rape Relief. Furthermore, she was able to pass Rape Relief’s pre-screening process. Further, Nixon showed Rape Relief that she agreed with their collective political and ideological beliefs. It was not until they found out that she was not born as a woman that they precluded her from volunteering with their organization.

This seems like trivial ground to preclude Nixon from volunteering because it is premised on an ideological ground that is abstract and has no practical bearing to the actual conduction of counselling. The idea that one has to be born a woman to understand women`s oppression is an abstract theory held by radical feminists and has no immediate or practical application to reality.

Mill would disregard Rape Relief's mission statement. He would likely argue that their view is contrary to the commun good and that anyone who is willing to provide a service, especially someone who has the experience and the proper ideological mindset to do so, should have the liberty to volunteer. To preclude Nixon from volunteering based on an abstract theoretical idea would be a restriction of her liberty at the detriment of society.

Aquinas would agree with the judgment and stating that the restriction of Nixon’s liberty would be against the common good and thus unacceptable. He would disagree with Mills' assertion that restricting Nixon's liberty works against the societal good. Aquinas would likely argue that enforcing the Human Rights Code is adhering to the legislative will.

On the other hand, radical feminist, would likely agree with the suspension of Nixon’s liberty. They would agree with the mission statement of the The Society. Radical feminists would agree that to be a woman is to be born as a woman into our oppressive patriarchal system. Radical feminists would disagree with Mills and argue that his view of the social interest is from a male perspective and supports the oppressive patriarchal system.

Legal Positivists, to some extent, would agree with the judgment. They would likely disagree with Mill and say that liberty is not a crucial issue at hand: the law is the law and it should be followed as long as it is made correctly.

Dworkin would also agree with the outcome of the case because Justice Saunders discharged her duty as a judge and ruled with principle, conferring rights on an individual or group, in this case, the Vancouver Rape Relief. He would likely disagree with Mill, and argue that because Justice Saunders discharged her capacity as a judge correctly according to Dworkin, the issue of liberty is not a concern.

Law and Economics: Law as Efficiency

Law and economics is a theory based on "efficiency". At the core of the law and economics theory is the concept of the cost-benefit analysis. The cost - benefit analysis is used to weigh the costs against the benefits to help determine whether a claim should be uphold or struck down.

Cost Benefit Analysis for Rape Relief

Costs

The cost to the Rape Relief Society to allow Ms. Nixon to volunteer would completely disregard the Society's private group rights and compromise their organizations objectives. The Society argued that if it were forced to allow Ms. Nixon to volunteer the quality of service provided for abused women may be compromised.

Although this may seem like a trivial cost, the very essence of The Societies purpose would be compromised. The Society holds giving women the absolute best chance at recovery as paramount, and, through their eyes, this is accomplished through women volunteers.

Benefits

The benefit to the Rape Relief Society of not allowing Ms. Nixon to volunteer would allow The Society to better meet their objectives and have the interests of private groups protected.

Cost Benefit Analysis for Ms. Nixon

Costs

For Ms. Nixon being allowed to volunteer at the Rape Relief Society there are very minimal costs associated to Ms. Nixon - She is an individual that is willing to participate in a capacity that may affect a few dramatically, but most insignificantly.

Benefits

The benefit of Ms. Nixon being able to volunteer is that it allows Ms. Nixon to define herself as a women and opens up the possibility of letting Ms. Nixon benefit other women or transgender rape victims. An argument may be that transgender rape victims have no relief outlets and allowing Ms. Nixon to volunteer at Rape Relief Society would allow a gateway to a more progressive and contemporary rape relief efforts.

Cost Benefit Analysis from the Perspective of Society

From the perspective of the public, in terms of the cost and benefits of prohibiting Ms. Nixon from volunteering at the Rape Relief Society - The major cost of disallowing Mr. Nixon from volunteering is that women and transgender rape victims may not be able to benefit from Ms. Nixon's service. While the major benefit of disallowing Ms. Nixon from volunteering from the perspective of the public would be that the law that protects private group rights are being protected for the good of a identifiable group.

The Law and Economics theory is similar to Bentham because both theories would agree that if Ms. Nixon could increase social utility by volunteering to a greater degree then the Society could by prohibiting her from volunteering then the judgment should be in favour of Ms. Nixon.

In contrast, Mill's would disagree with the basis of the law and economic theory because Mill's believed that the liberty of the individual is paramount. Mill's believed liberty is not the only value but is key and that in our society we must give the benefit of the doubt to the individual - in this case Ms. Nixon.

Positivists ideology would also not coincide with the law and economic theory. Positivists are only concerned with whether the laws are valid and if the law is valid society has a moral obligation to follow the law. Positivists would reject the idea of balancing benefits and costs of laws and would completely disregard the idea of the rational man and wealth maximizer - that the law and economic theory strongly adheres to.

Feminism

The question of whether The Society should be entitled to exclude a transgender women on the basis of her biological sex presents a dilemma for feminist jurisprudence. By turning away Nixon because of her genetic sex the ruling goes against a core tenet of feminism - that gender is a social construct that is neither natural, nor inevitable. To put it another way, by defining Nixon on the basis of her biology rather than her gender Vancouver Rape Relief is prescribing the same sort of biological determinism that feminists refute and have fought against. The remainder of this section will present an analysis of the ruling from the perspective of the varying feminist schools of thought.

Liberal Feminist Theory

Liberal Feminist theory posits that, human beings as "moral equals", women are entitled to equal treatment under the law. In the same vein, they put forth that no one - on the basis of their gender, race, ethnicity, or other characteristic - should be excluded from participating in the public or private domain.

The ruling in Rape Relief directly contradicts this principle. The case turned on the basis of Ms. Nixon's gender alone, and Justice Saunders, though noting that this was discriminatory, allowed for it. Saunders J stated that a not-for-profit organization catering to a specific group is afforded the right to certain discriminatory practices outlined under the Human Rights Code.

Mill would likely take issue of assuming that women posses "Mature Facilities". Through the eyes of Mill, individuals who lack mature facilities are not inherently entitled to exercise liberty rights. As such, Mill would likely point out that Ms. Nixon did not suffer as a result of the ruling in Rape Relief

Radical Feminist Theory

Radical Feminist theory posits that gender is a patriarchal social construct essentially designed to subjugate women. The social construct is so extensive that it permeates every aspect of our lives and therefore appears to be natural, or in other words based on biology. Therefore, Radical Feminist believe the only way to change the system, is to reexamine our nature and relation to others. This is not to say that biology does not have a role to play. Indeed, Radical Feminists emphasize the importance of biology in defining the female experience. Yet, they believe that the patriarchal system subsumes the role biology plays by aligning women with a prescribed set of activities.

In the context of Radical Feminist theory, the ruling in Rape Relief, on the one hand affirms the patriarchal gender roles they oppose and at the same time reflects the importance of biology in defining the female experience. This view is more in line with what Rape Relief Argues. That there is the obvious importance of having a women’s only environment for victims of rape and sexual abuse but more so than that although Nixon regards herself as a women and perhaps always has, does not change the fact that she is transgender and has experienced life not as a women but as a transgendered women.

Marxist-Socialist Feminist Theory

Marxist-Socialist feminism is a branch of Radical Feminist theory that posits that the oppression of women is a function and reflection of the capitalist system. They argue that by placing monetary value on labour, the system essentially de-values the "private" domestic sphere and with it, the value of child bearing and rearing, and home-based tasks such as cooking and cleaning. Because women typically embody the domestic sphere, by virtue of devaluing the domestic sphere, the system essentially functions to de-value women as well, and therefore leads to there oppression.

With it's focus on the economic system, Marxist-Socialist feminism does not lend itself well to an analysis of the Nixon case. However, and in the same vein as the Radical Feminist viewpoint, because Nixon was born a man (and has lived much of her life as one), she has never truly experienced the oppression experienced by a biologically-born women. Being a born a man, any oppression Nixon experienced as women, was out of choice, and not imposed on her through the capitalist system.

Postmodernist Feminism

In direct contrast to other branches of feminists theory, Postmodern Feminism denies the usefulness of categorical, abstract theories, (referred to as "Grand Theories”), in explaining the role of women and the female experience.

The Postmodernists refer to such ambitious theories as being, “phalologocentric”, meaning that they are centred on an absolute word and are reflective of a male perspective. In other words, it is an entirely male-oriented approach to believe that a single answer or a single truth can be found that will simultaneously distill all the issues and lead to a single answer. As the foregoing suggests, Postmodernists do not offer a single solution to the oppression of women; to do so would be to assume that all women suffer the same oppression. Rather they embrace and celebrate women's position within the patriarchy as the "other" and believe the objective should be to encourage diversity.

In the abstract, the ruling in Rape Relief, reflects the sort of "Grand Theory" application that postmodern feminists oppose. Justice Saunders, in reaching her decision, applied a general provision that afforded not-for-profit organizations the right to engage in discriminatory hiring practices. This did not directly take into account or necessarily reflect the needs of both Vancouver Rape Relief or Nixon but rather represented a blanket application of the law.

Post Modern Feminists would likely take the factual background of Ms. Nixon into account; Ms. Nixon was abused herself, she likely suffered an even higher level of abuse due to her post-operative sex, and she still managed to overcome these massive hurdles and offer help to other women. Thus, a more fitting solution for postmodern feminists would likely be one in which Nixon were allowed to work at Vancouver Rape Relief. However, Postmodern Feminists would likely argue that her history be made aware to women seeking council allowing them to choose whether they would like to be treated by Ms.Nixon.

Postmodern feminists may even celebrate Ms. Nixon as part of the "others" and argue her inclusion in The Society would further encourage diversity and women's position within the patriarchy.

Critical Legal Theory

Critical Legal Theory focuses on the relationship between law and political relations (or power relations). Here, political has both a formal and non-formal dimension, encompassing both the political framework and human relations in general. In this framework, the law is used by the powerful as a means to maintain their power and interests.

Rape Relief provides a compelling example of power relations. Here the law recognizes that rejecting Nixon on the basis of her biological sex was discriminatory. It nevertheless uphold's Rape Relief's right to do so on the grounds that as a not-for-profit organization catering to a specific groups they were entitled to certain discriminatory hiring practices. Justice Saunders, in concurring, notes that the purpose of the particular law here is to maintain social harmony:

"To force people, especially those in an organization such as the respondent, which has its own radical agenda, to associate with those who for some reason deeply offend their own avowed principles, can lead not to acceptance or at least toleration, but, if not to hatred, at least to animosity." paragraph 83.

Critical Legal Theorists would reject that notion. They would argue that any effort to maintain social harmony was incidental to the main purpose of the provision: to ensure that Humans Rights legislation does not encroach on the rights of certain powerful groups from having to associate.