TRU/Law3020/GroupD

Contents

[hide]- 1 R. V. OAKES Theoretical Legal Perspectives

- 2 Legal Realism Oliver Wendell Holmes

- 3 Natural Law

- 4 Positivism

- 5 Separation Thesis: H.L.A. Hart HLA Hart

- 6 The Morality of Law Lon Fuller

- 7 Law as a System of Rights (Dworkin) Ronald Dworkin

- 8 Liberty and Paternalism Gerald Dworkin John Stuart Mill

- 9 Law and Economics Richard Posner

- 10 Feminist Jurisprudence Catherine Mackinnon

- 11 Critical Legal Studies and Critical Race Theory Carol Aylward

R. V. OAKES Theoretical Legal Perspectives

Legal Realism

The Theory of Legal Realism views law as a means to achieve a social end. Jerome Frank argues that judges essentially work backwards. They begin with the results they want to achieve and then use this to determine their reasoning with judicial discretion. For Frank, if the law consists of decisions that are based on “judicial hunches,” the source of these hunches are the rules and principles of law. However, since all judges are human beings, hunches are always formed by personal preferences, prejudices, sympathies and experiences. Theorist Oliver Wendell Holmes also states that judges have significant discretion and can essentially decide indiscriminately on issues put before them in court. This idea is completely contrary to Ronald Dworkin, who argues that judges do not have discretion. For Dworkin, judges are obliged to follow principles and through these they discover rights; they do not create them. For Legal Realists, the Oakes Test would be seen as a way to disguise a judge’s subjectivity. Frank would likely view Dickson C.J.’s analysis in Oakes as using his judicial “hunch” and personal prejudices, rather than obligingly following principles. He would say theOakes Test assists judges to use their discretion, and may reflect even trivial things (like how the judge felt on a given day) when justifying serious matters like Charter infringements.

In viewing the law as a means to achieve a social end, Legal Realists would argue that, in Oakes, the legislation sought to curtail narcotics trafficking as the social end that they wish to obtain, and by legislating s. 8 of the NCA, this is the means of achieving this objective. Furthermore, the Realists would assert that the Charter exists to protect individuals and their rights and this is the social end that the law must achieve. The Oakes Test is the means of achieving these protections by ensuring that any Charter right infringements are justified. Also, within the Oakes test itself, a rational connection is required between the means chosen and the objective of why the law itself is in place. This requirement quite clearly speaks to the Realists’ idea of “law as a means to achieve a social end”.

Similar to Hart, Legal Realists argue through the “separation thesis” that law and morality are always separate. While morality and law may sometimes follow the same path, they do not intermingle. Positivist Theorists would similarly argue that the two may run parallel but are still distinct. For Positivists, it is acceptable that the two interact, but when they do it is merely coincidental. With respect to Oakes, Legal Realists would agree with Positivists’ approval of the court not referring to morals in their judicial reasoning; they strictly focused on the underlying principles of fundamental justice.

Discussion-Motivated Reflection Critique

Our discussion this week centered on Lord Denning’s approach to judicial decision-making. It was clear that we had all noted that his methods are often quite subjective. It was not until learning about legal realism that we were able to correctly label his approach. It seems impossible to believe that any judge would openly affirm the assertions of Legal Realists, yet Denning’s approach appears so unabashedly subjective that we struggled to conclude otherwise. Ultimately we agreed that all judges are subjective to some degree, and are distinguished by the extent to which they disguise their subjectivity with legal justification – presumably the same conclusion promoted by Legal Realists.

Natural Law

Overview

Traditional Natural Law Theory asserts that law has its foundation in a higher source. That source establishes an independent standard against which all genuine human laws are measured. Laws are teleological, in that they can only be properly understood in understanding their end, which is to achieve the common good. These laws must be obeyed, not simply due to their deterrent nature, but to ensure justice and morality in society. In pursuit of the common good, laws must be rooted in moral goodness, and those that fall short of this standard need not be adhered to, as “an unjust law is no law at all” (Classic Readings [text], p. 3).

St. Thomas Aquinas

St. Thomas Aquinas is the leading figure of Traditional Natural Law theory. How would he have approached R. v. Oakes? A good starting point is his four elements of a valid law. To be considered valid, a law must: o 1. be directed to the common good o 2. follow practical reason o 3. be made by a valid lawmaker, and o 4. be promulgated. The Charter challenge in Oakes suggested that s. 8 of the NCA was invalid because it induced a reverse onus provision, shifting the presumption of innocence and thus infringing s. 11(d) of the Charter. Would Aquinas find s. 8 to be valid?

Directed to the Gommon Good

Aquinas is clear that the common good refers to the good of the community as a whole rather than what is desired either by individuals or even a majority of the people. In Oakes, the good of the community is at stake and accordingly is examined. Aquinas would see that the court in Oakes used the principles of fundamental justice appropriately as a measure of the common good, in relation to s. 8 of the NCA. For Aquinas, as laws must be created with our God-given reason, use of Charter principles is key to ensuring validity. Moreover, valid law creates order, which enables us to keep our eye on the common good. Aquinas would support the court’s reference to Charter principles to illuminate the path set out by our laws to serve their ultimate purpose: achieving the common good.

Following Practical Reason

For Aquinas, laws are God-given practical reason applied to satisfy the common good. A valid law would have to follow this reason. Accordingly, Aquinas would approve of the court applying the Oakes’ Test to determine whether or not s. 8 of the NCA followed practical reason enabling it to reach the common good. Step one of the test attempts to locate any pressing and substantial concerns of the provision. This appears to be a rough outline of the common good. The second step of the test, proportionality, focuses on the reasonableness of the means chosen. In this way, the court seems to adopt practical reason to determine whether the law is rationally tailored to its objective. Aquinas would eagerly endorse the

approach taken in both steps, as they provide a way for courts to measure both practical reason and the common good, and to what degree the law in question follows the former to achieve the latter.

Made by a Valid Lawmaker

Aquinas holds that natural rulers are uniquely aware of the common good. From this vantage point, they have a duty to use laws to deter, threaten, and punish their subordinates (the “ruled”). Consequently, he would find that the judges inOakes were perfectly placed to make their determination regarding s. 8 of theNCA. With a clear view of the common good, who better to make such a determination? Alternatively, Legal Realists would dispute the neutrality of these judges. They would insist that, far from being neutral arbiters of a higher law, these judges are instead influenced by their respective backgrounds, forming their decisions on a purely subjective basis.

Promulgated

The final element of a valid law asserts that if a law is not promulgated, it cannot be valid law because it has failed to serve its purpose – leading people to the common good. Absent awareness, citizens have no way to understand law, and thus are denied the light required to illuminate the path towards the common good. The Oakes Test is a way to spread knowledge of the law, by providing a determinative approach to both the common good and practical reason. Aquinas would applaud Oakes for drawing awareness to laws through an analytic framework that champions valid law and destroys invalid law.

Legislation Supersedes Common Law

Aquinas preferred law to originate in the legislature rather than the courthouse. However, he would likely be satisfied with the approach taken in Oakes. While the Oakes Test was a judicial approach to the validity of a law, it had its’ origins in legislation (the Charter). He would have viewed this method as the correct interpretation of the legislation – of the will of the lawmakers – and as an essential approach to clarifying and promulgating the law towards the common good. John Stuart Mill would take issue with this approach, rejecting the importance of any meaningful distinction between legislation and judge-made law in regards to limiting personal liberty. His perspective would refuse any law that threatens individual liberty, regardless the source.

Judicial Interpretation

Unlike the view of Legal Realists, Natural Law Theorists hold that judges aren’t just subjectively evaluating law, but rather are interpreting it to ensure both the spirit and letter of the law remain normatively consistent. In rare cases, the spirit of the law will override the letter of the law. Aquinas and his fellow theorists would locate this aspect inOakes, wherein the principles of fundamental justice tend to support the spirit of the law, even where they infringe the letter of the law. Similarly, in Lavalee – the accused argued the spirit of the self-defense law. While she did shoot her husband as he walked away from her and out of the room, that may have been her one chance to save herself. She believed she had to kill him then or be killed. Surely this upholds the spirit of the law of self-defense, even while it runs contrary to the letter of the law. The common good in this case would be suppressing social ill: battered women. This good can only be attained if interpreted so as to favour the spirit of the law at the expense of the letter of the law. Thus, Aquinas would also support this finding.

Discussion-Motivated Reflection Critique

Our discussion was greatly influenced by legal realism, the previous week’s perspective. These two theories’ near diametric opposition made it difficult for us to accept some of the principle assertions of Traditional Natural Law Theory in light of the positions held by Legal Realists. It seemed we were largely in favour of the realist perspective, thus statements such as “judges aren’t subjectively evaluating the law, but interpreting so as to maintain the path to the common good” were tough to accept. This was an early demonstration of the power of a legal perspective to colour one’s interpretation of other legal perspectives.

Positivism

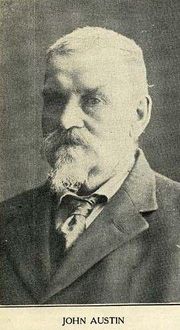

Positivism is well defined in its opposition to the central tenets of the Natural Law Tradition. Some features of positivism differ in noteworthy ways between different Positivist thinkers. Perhaps most significantly, Positivists such as Austin take a strictly empirical approach to determining whether or not a law is valid. Hart, on the other hand, allows for some grey amidst the black and white. He contends that whether one obeys a law should depend on the degree of that law’s injustice and the consequences of disobedience.

Austin would find section 8 of the NCA to be valid as it meets his three specific criteria. S.8 is a command, issued by superiors to subordinates, and backed by sanctions. Not only would Austin disapprove of a judicial attempt to invalidate s.8, but, as his approach values legislation over the common law, he would argue that Dickson’s judgment should apply only toOakes himself, and should not be applied as a general rule for society.

Hart, on the other hand, would employ the “Pedigree Test”. In doing so, he would examine if the law was created in accordance with the rule of the law within the law-making jurisdiction. This assessment of whether or not a rule is law, would allow one to only look to the law’s form and institutional history without scrutinizing its content and morality. While Hart might engage a competent person, such as a Moral Philosopher, to assess the moral “quality” of the law, this would not enter into his analysis of whether or not the law is valid. The reason being that the Positivists claim, “a rule may be legally valid and yet morally objectionable” (p.34). This type of analysis would not likely result in a determination that section 8 was invalid.

Raz and Bentham put forward alternative theories of evaluation. Raz determines if laws are justified by whether or not they perform a service for the citizens of the state. From his perspective, laws that are not justified do not need to be followed because they are only human rules. Raz would likely view the service that s.8 is meant to achieve to be the furtherance of the safety of citizens. The reverse onus reflects Parliament’s intention to curb the dangers inflicted upon society by an increased proliferation of illegal substances. Since this would be seen as a worthy service, there would be no need to disobey this law.

Bentham, as the founder of Utilitarianism, would be chiefly concerned with whether the law produced the greatest happiness for the greatest number. It would be of significance to Bentham that not all citizens, going about their daily lives, would be subject to this law. Only people convicted of the offence of possession would bear the weight of the assumption of trafficking. While the law would unquestionably limit the “happiness” of those charged with possession, it is possible that Bentham, like Parliament, would see the social utility of such a provision. He would then weigh the limited class of persons negatively affected by the reverse onus against the promotion of safety for the public at large. This balancing would result in an affirmation of section 8. On the other hand, if Bentham perceived putting more people in jail as counter to social utility, he may weigh the factors differently, achieving a different result. However, because Bentham was strongly in favor of extending individual rights, he would most likely invalidate section 8 insofar as it did not reflect the presumption of innocence.

Making Connections

Natural Legal Theory and Positivism clash in noteworthy ways. Firstly, they differ in terms of the source of law. The natural legal tradition sees the law as beyond human creation. Therefore, they see that law as being unchanging and universal, with divine command at its source. Positivists, on the other hand, argue that there is no inherent connection between law and morality. They see the law as a human creation.

Secondly, the two schools of thought also differ in terms of the law’s objective. Natural legal theorists argue that the function of law is to work toward the common good. Thus, laws are morally good. On the other hand, positivists assert that not all laws are just. Indeed, some law may be extremely unjust, and the state which sanctioned them may be illegitimate. In this situation, the result may be that there is no obligation to obey such laws.

Both theories advance the notion that adhering to laws is good. The Natural Law Theorists argue, almost without exception, that one is obligated to adhere to laws which are innately just. However, the Positivists allow for more discretion. Since observing that some laws are unjust, the individual needs to balance the importance of obedience with his or her own convictions.

Discussion-Motivated Reflections and Critique

Our group felt that Legal Positivism “filled in some of the gaps” left by natural legal theory. Certainly some “natural laws” exist, and they exist universally regardless of race, culture or class. These laws exist as truths, regardless of whether they are documented by legislatures. For example, without exception, rape and child pornography are deemed wrong. How do we know this? The Natural Law Theorist would suggest that God has imbued us with wisdom and insight as rational people.

While natural law makes sense in a discussion of certain moral absolutes, it does not help to explain why unjust, even evil, human laws have, and still do, exist. The Natural Legal Theorist struggles to make sense of the German Nuremburg Laws and the American Jim Crow Laws. Certainly not all laws are God given, because a purely good God would not create such laws. This is where the positivist claim becomes more appealing. The positivist states that laws are human creations. If laws are created by humans, then humans may break them.

Separation Thesis: H.L.A. Hart

At the core of H.L.A. Hart’s Separation Thesis is the separation of law and morality. While Natural Law Theorists suggest that the law lies within morality, Hart sees law and morality as two separate systems, with two separate sets of rules and standards. While they are not the same, the two frequently run parallel and in fact, we may evaluate legal rules with reference to moral rules. Hart suggests that laws need to have “ought claims” on us such that we feel that we ought to follow them. As with morally neutral rules (such as the rules of a game), “ought claims” do not necessitate moral judgments. This system of law contains legal rules which grant rights and duties to those governed by the system. Hart would likely approach the issues in Oakes by first showing that the court had a legal duty to uphold the right to the presumption of innocence, however, any moral duty the court may have in doing so is grounded in a different rule system and is to be kept separate. Hart would likely approve of the way the court avoids any actual discussion of morality in relation to the law in their judgment.

Hart explains that laws are expressed in general terms and that laws have a core of settled meaning. Cases that fall outside the settled core are in the penumbra where meaning is unclear or indeterminate. Hart says these are “hard cases” in which it falls to the judge to decide whether the case falls within a core of settled meaning. Hart would say the reverse onus provision at issue in Oakes is an unsettled, hard case that sits in the penumbra.

Hart further discusses that where there is no rule that applies to a novel case, it is the role of judges to fill the gaps by making law and exercising discretion - a controversial issue for Dworkin. In deciding penumbral cases Hart explains that laws must be understood in terms of the rule governed practices that gave rise to them; these are the underlying fundamental ideas of our legal system. In Canada, the Charter contains most of these ideas. Of particular concern in Oakes were the principles of fundamental justice, objectivity, and the presumption of innocence.

Hart would suggest that the law at issue here s. 8 of the NCA is expressed in such general language that its meaning is unclear as to how it should apply with respect to the presumption of innocence. In this way there is a gap in the law which the judges here must fill. While, Oliver Wendell Holmes would see this as an opportunity for judges to impose their will, Hart instead proposes that judges draw on the terms of the rule governed practice in their law making. In this way there is a consistent set of principles underlying penumbral judicial decisions. In addressing the penumbral issue in this case, Dickson C.J. explicitly demonstrates Hart’s point when he says,

“The Court must be guided by the values and principles essential to a free and democratic society which…[are] the ultimate standard against which a limit on a right or freedom must be shown, despite its effect, to be reasonable and demonstrably justified.” (Dickson C.J. para 64)

Throughout Oakes the court refers back to the principles of justice underlying the law and the Charter. The court addresses the gap in the law by formulating what we now know as the “Oakes Test”. Hart would likely also approve of the test itself which necessitates continued consideration by courts of the underlying principles of our rule governed practice. This is particularly evident in the proportionality test applied in step 2, which assesses whether there is proportionality between the objective of the provision in question and the effects it has on the individual and his or her rights.

H.L.A.Hart would likely agree with the approach taken by the judges as well as the final outcome in R. v. Oakes. The court has clearly applied the judicial principles associated with this as a “hard case” and made a very detailed analysis and application of the values underlying the Charter (the terms of our rule governed practice). Additionally, the court maintains the separation of morality from law throughout their decision. For these reasons it is likely Hart would see R. v. Oakes as a very well decided judgment.

Discussion-Motivated Reflections and Critique

This theory caused our group to consider what lies behind the “ought” claim and whether or not an “ought” can exist apart from morality. We discussed the possibility that, at the heart of most ethical and legal debates, is what comprises the moral “ought”. The Natural Law Theorists would likely assert that the “ought” is based in human nature, perhaps even as a form of conscience, given to humans by God. A Positivist, on the other hand, would posit that an “ought” claim does not need to be grounded in morality or impose a moral duty.

This leads one to consider whether or not “ought” can be a relative claim. Is what you “ought” to do, different from what someone from a different culture or background “ought” to do? The Natural Law Theorist would likely answer this in the negative because God, the one who gave us our conscience, is unchanging. His laws are universal. The positivist, on the other hand, would likely have a more flexible and relative approach.

Hart’s distinction between cases in the core and the penumbra resonated with us. Seeing cases differentiated in this way demonstrates why certain cases are chosen for our law courses. This also helps us understand why various cases carry different weight as authorities.

The Morality of Law

External Morality of Law

The court’s reasoning in Oakes is strongly linked to certain features of the morality of law, and specifically to Fuller’s conception of the external morality of law. Dickson C.J. speaks of the “cardinal values” underlying the presumption of innocence, and that presumption’s labeling as a hallowed principle protecting fundamental liberty and human dignity. Such descriptions allude to the external sources of law, a necessary requirement since “law cannot be built on law.” These external sources are crucial for judicial interpretation. In Oakes, Dickson C.J. asserts that a court must rely on essential societal values and principles to justify limitations on rights and freedoms when he says (at para 64) "[t]he underlying values and principles of a free and democratic society are the genesis of the rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Charter and the ultimate standard against which a limit on a right or freedom must be shown… to be reasonable and demonstrably justified."

This reveals morality as the foundation of legal rights and freedoms, a clear congruency with Fuller’s expression of external morality’s relationship to law. Indeed, when Dickson C.J. suggests (at para 61) that denying Oakes his right to be presumed innocent is “radically and fundamentally inconsistent with the societal values of human dignity and liberty which we espouse…”, he solidifies this connection. The denial of Oakes’ s.11(d) right cannot occur without first measuring it against the external morality of law.

Oakes Analysis

Fuller would likely concur with the approach taken by the court. Dickson C.J. chose a purposive approach to his interpretation of the infringing statute and to his examination of s. 1 and s. 11(d) of the Charter. For each of them, he concerned himself with the underlying purpose of the legislation in light of underlying societal values. Fuller would champion this approach. He believed judges should “… interpret a legal rule or precedent as a whole, using a set of beliefs about what the given rule or precedent was designed to do, what purpose it was designed to serve, and what good it was meant to accomplish.” (Classic Readings [text] pg. 209)

In Fuller's view, this is the only proper method of interpretation; in order to determine the good targeted by a law, judges must examine broader moral standards as well as the inner morality of law. Once again there is a strong link between morality and law, a link Fuller argues is essential to the existence of legal morality. Consequently, legal morality cannot live when severed from its journey toward justice and decency. This aligns with Dickson C.J.’s view in Oakes that fairness of legal infringement cannot be considered without determination of the good at which the law aims. Fuller believes that without this determination, judges are deprived of their sacred function, thus rendering them unable to defend the moral standards of a legal system.

Inner Morality of Law

Through the lens of Fuller's "inner morality of law" and eights ways laws fail, he would likely agree with the finding that s. 8 of the NCA was of no force and effect. The provision specifies that a person found guilty of possession of a narcotic would be presumed to be in possession for the purpose of trafficking. This places a reverse onus on the defendant to disprove. In this way s.8 explicitly contradicts the presumption of innocence set out in s. 11(d) of the Charter. That laws not contradict each other is one way Fuller says rules fail to be law. Without fulfilling this internal requirement s. 8 is unable to produce order, which Fuller says is the very purpose of law.

Fuller would also likely find a failure in s. 8 of the NCA because it does not clearly tell people what to do. This contradicts Fuller’s position that laws must be coherent in order to function as law and that coherence requires reasonableness, rationality and consistency. Where s. 8 is unclear on how people are to behave, it defies predictability and thus is bad law.

With respect to the other internal requirements it seems clear that “laws must be public”, “laws must not be retroactive”; “laws must be understandable”; “laws must not require the impossible”; “laws must not change too rapidly”; and “laws must be consistent with their administration” would all be met by s. 8 of the NCA.

Fuller would approve of the Oakes Test because it can be used as a way to resolve contradictions n the law. The court in Oakes attempts to reconcile the contradiction between s.8 of theNCA and the Charter through the use of the s. 1 test.

With respect to the rational connection requirement within the Oakes test, Fuller would argue that this is a further explanation that laws have to be reasonable and rational. In Oakes this stage is where s. 8 of the NCA failed because there was no rational connection between possessing a small amount of narcotics and the presumption that the narcotics were intended for the purpose of trafficking. The presumption that everyone who possesses narcotics does so for the purpose of trafficking is too extreme to be rationally connected to the objective of s. 8 of the NCA, which is to address drug trafficking issues and related problems.

Another of Fuller’s requirements for inner morality in law is encompassed in s. 1 of the Charter: citizens should know the standard to which they are being held to and law should be understandable. It can be argued that because s. 8 of the NCA is contrary s. 11(d) of the Charter, is somewhat confusing for citizens. Citizens are generally aware of their right to the presumption of innocence and by having a provision contrary to this, it makes it difficult to know which standard you are being held if they are inconsistent. Fuller would argue that s. 1 can be used to bring some understanding to provisions that contradict other law and elaborate on the standard to which citizens will be held. While s. 1 is unable to do this in Oakes specifically, the Oakes test does have this ability and therefore Fuller would argue that s. 1 is good law.

Potential Areas of Disagreement

Lon Fuller might not have agreed with the Oakes decision if he had examined the impugned legislation without reference to the Charter. Fuller stipulated that a judge should examine “what the rule was designed to do… and what good it was meant to accomplish.” The purpose behind the s. 8 of the NCA was to negate the evil of drug trafficking. Drug trafficking was becoming an increasing problem in society and diminishing its effects this was the purpose behind the reverse onus. The Legislature was intending to target individuals like Oakes, and Fuller might have seen Oakes' conviction to be aligned with this purpose.

However, after considering the purpose of the law, Fuller states that moral standards from both inside and outside of law will need to be referenced. It is in this aspect of his analysis where Fuller might see the merit in upholding s. 11(d) over the NCA provision. While Fuller does not explicitly express that some laws may be more moral than others, he does refer to Hart’s “immoral morality” in relation to the Nazi system. In this discussion, he seems to express that Nazi-morality was a corrupt and evil form of morality. If it is possible to have both good and bad form of morality, this would suggest that some morals are better than others.

In light of this, Fuller might have seen s. 11(d) as more important, morally speaking, than the Narcotics provision. Furthermore, the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty would be more likely to fit within Fuller’s larger principles. It is for these reasons Fuller would likely not have upheld s. 8.

Discussion-Motivated Reflections and Critique

The story of Rex was a light-hearted read but it demonstrated to us very clearly how law cannot function well without certain essential features. Fuller’s eight ways laws fail demonstrated to us that some of the more systematic and policy reasons why laws may be overruled. When rules produce conflicting results this can create a serious predicament for citizens and societal structures, and can deteriorate the legitimacy of law. We found applying the principles from the Rex story was really beneficial to our understanding of some of the reasoning for the decision in Oakes. We also felt that we could take a lot away from this analysis and apply it particularly to our understanding of federalism in our constitutional law class.

Law as a System of Rights (Dworkin)

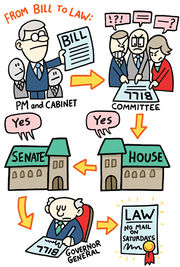

For Dworkin, law contains rules and principles. The principles are legally binding and the rules are embedded within these principles and are therefore consistent with them. InOakes, Dworkin would view the Charter as the principles and the rules, therefore, have to be consistent with the Charter in order for law to be established. Oakes deals specifically with s. 11(d) of the Charter, which is a fundamental principle of justice that ensures that everyone is presumed innocent until proven otherwise.

Hart, a modern positivist, would argue that the Oakes case is a “hard case”. A hard case is a one that is not determined by legally binding standards. However, Dworkin rejects Hart’s theory of the penumbra and the idea of “hard cases”, in which judges exercise discretion by drawing on the terms of the rule governed practice in order to decide the outcome of a case. Dworkin says there is always a right answer and where the rules do not decide the outcome of a case, the principles will be used by judges to “discover” rights and duties based on these principles. This idea is similar to the Feminist perspective since Feminists argue that if legal reasoning is done properly, it is going to achieve the right outcome, which is fair and just. In Oakes, Dworkin would argue the right answer to the case derives from the application of the Charter (the principles) by the judges and the judges are bound to comply with the Charter instead of using discretion. Specifically, if there is no precedent from other cases or rules already established on whether s. 8 of the NCA’s reverse onus is an infringement of the Charter, the principles set out in the Charter itself will give the answer and that will then come to stand for a new rule.

In addressing this case, Dworkin would say that the judicial reasoning is like a chain novel in which it is always looking backwards and forwards in interpretation to create an overall, coherent story that expresses justice and fairness in the community. This is contrary to the Legal Realist idea that each judge makes an independent decision as well as contrary to Hart’s interpretation of judicial discretion because for Dworkin the judges are building off of each other and have to work with what they are given. The chain novel metaphor is the whole idea behind common law; one judge makes a decision, which is later refined by another or tweaked according to a certain situation. The Oakes Test under s. 1 was created this way – framing judgment in the content of previous precedent and then building upon it.

In accordance with this, Dworkin would find s. 8 of the NCA inconsistent with the principles set out in s. 11(d) of the Charter. Since principles have a quality of weight and importance that rules do not, Dworkin would argue that the principles would outweigh the rules established in the NCA under s. 8 and therefore be considered an infringement on the principles established in s. 11(d) of the Charter.

For Dworkin, principles should be thought of as an underground stream. Both rules and principles are informed by the past and they flow into the future. As the metaphor goes, sometimes the water flows up into the river and the waters are mixed and this process is akin to rules being changed by their infusion with the principles. The infusion itself could represent the judging process since judges use principles in deciding cases. Thus, Dworkin would have ruled the way the Supreme Court of Canada did in finding that s. 8 was an infringement of s. 11(d) of the Charter. In attempting to find the best fit with the principles (Charter) and rules (NCA), Dworkin would turn to s. 1 as an attempt of ensuring the principles and rules are consistent.

Principles, Policy and Politics

Furthermore, Dworkin looks at the similarities and differences between principles and policy. Principles and political processes are interwoven and judicial decisions enforce existing political rights. However, judges are directed by arguments of principle, whereas legislatures are directed by argument of policy.

According to the rights thesis, the judicial decisions enforce existing political rights. Policy justifies a political decision by showing how the decision protects a goal of the community, which is contrasted with the argument that principles justify a political decision by showing it advances or protects an individual or group right. In Oakes, Dworkin would see the policy established in the NCA in its attempt to protect the community from narcotic trafficking and curtail narcotic use. Additionally, as previously mentioned, he would see the Charter as the principles since they protect the rights of all individuals in Canada.

In accordance with the integrity of the law, judicial decisions must be consistent and Dworkin would therefore see s. 8 of NCA as inconsistent with the Charter under s. 11(d), which would be problematic. The courts are trying to keep the policy and principles in line by enacting the NCA, but the two cannot be intertwined appropriately in this case since the Charter right would be infringed by upholding s. 8. Furthermore, turning to s. 1, Dworkin would most likely agree with the Supreme Court of Canada in finding that s. 8 of the NCA fails for rational connectivity because the integrity of the law’s requirement for consistency would be violated here. An established element of justification is a rational connection to the objective (to curtail drug trafficking; policy reasons) under the Oakes Test, and to not follow this would be inconsistent. Dworkin would not find it surprising that the Charter overrode the policy because for Dworkin, the judges use principles to govern law and rules.

The Feminist perspective argues that law is never separated from politics. On the other hand, Dworkin sees principles and political processes as interwoven and pre-existing rights are “political” since they are the produce of history and morality. However, while these perspectives of law are similar on their belief that law and politics are connected, Dworkin would argue that where policy supports a political view that is contrary to principles, the principles will override the policy and therefore severe the connection with politics. Thus, Dworkin sees the relationship between law and politics as more fluid than feminists do.

Additional Connections:

As previously mentioned, Dworkin sees principles as legally binding and the rules are embedded consistently within these principles. However, Posner in his discussion of Law and Economics argues that insufficient rules generate litigation and this litigation eventually changes the rules. Dworkin would disagree with Posner because for Dworkin there is always a right answer and the principles can be used to influence the rules and therefore it is the principles specifically that change the rules, not litigation.

Discussion-Motivated Reflections and Critique

In our discussion, our group found Dworkin’s distinction between rules and principles to be an important one. After spending several classes in our Constitutional Law and Criminal Law courses discussing s. 11(d) and s. 1 specifically, and other Charter rights in general, the importance that Dworkin places on “principles” depicts the importance that these rights have in our society.

We found a lot of the discussion on policy, politics and principles to be reflective of society. Often legislation will reflect a political decision or policy, but ultimately the Charter governs Canadian society and must be given the ultimate say in respect to the law in order to properly protect our interests. Our group thought Oakes was a good demonstration of this. While drug trafficking is certainly something that causes a problem for society, infringing a Charter right in order to curb this problem to the extent that s. 8 of the NCA suggested, is not rationally connected to the objective. Furthermore, the application of s. 1 as a way to reconcile rules and principles was something we all agreed with Dworkin about, since throughout our courses we have discussed how Charter infringement can only be reconciled with the rules in certain circumstances (i.e.where the steps of the Oakes Test are met).

Liberty and Paternalism

Overview

John Stuart Mill was concerned strictly with protection of individual liberty, although he acknowledged that some circumstances required interference. His starting point is a presumption of liberty, and any restriction against it must rebut that presumption. Accordingly, he sought to determine when restrictions on individual liberty were justified.

Gerald Dworkin challenged Mill by expanding his exceptions to liberty restrictions in the harm principle. Dworkin argued that interference with individual liberty is justified when done so to prevent harm to that person (and not only to others, as per Mill). Incidental harm prevention to 3rd parties may also arise in paternalistic interference, which Dworkin believes can actually protect individual autonomy when it prevents long-term damage to that person (specifically in cases involving irreversible and destructive harm to his/her liberty).

Harm Principle

Mill asserted in his harm principle that restrictions on individual liberty should arise only to prevent harm to others. He would have approved of the approach taken in Oakes. The accused’s liberty had been threatened in light of s. 8 of the NCA’s presumption of possession for the purpose of trafficking, but was measured via the Oakes’ Test against the social ill of drug use in society. Thus, the restriction on his liberty occurred in the context of an evaluation of the potential harm to others.

Significantly, Mill rejects infringements to an individual’s liberty solely to prevent harm to that person. Consequently, Mill would not endorse s. 8 of the NCA in that it targets individual drug use (possession), and then simply assumes a broader societal harm (via trafficking).

Alternatively, Dworkin would argue that Oakes was not merely a case concerned with societal ills, but also involved the threat of Oakes harming himself. He would support the courts’ concern with the threat of drug use in society, but would insist that the finding take into account the potential of individual harm. In contrast, Mill would say that Oakes, and not the state, is best situated to know what’s right for him. Mill would rail against state-imposed individual liberty restrictions, and question the state’s right to make such a decision for him.

Tyranny of the Majority

Mill believed that authority, comprised of delegates of the people, provides a crucial link between the state and the masses, but that authority exposes a society to the threat of the tyranny of the majority. This tyranny, taking the form of a society’s collective power over the individuals who compose it, must be protected against. Thus, the degree to which majority opinion could interfere with individual liberty would require a limit. Mill would argue that the system (the powers that be) crossed that limit in Oakes simply by charging him. A charge of simple possession, wherein a drug user would only bring harm to himself, would exemplify Mill’s concern regarding majority will superseding the an individual’s liberty; this is Mill’s tyranny of the majority. However, the court ultimately righted this wrong by striking down s. 8’s assumption of possession for the purposes of trafficking. Mill would applaud this decision, believing it was an appropriate limit to the threat of the tyranny of the majority.

The core of Feminist theorists would agree somewhat with Mill’s perception of this tyranny, in that the structure of the majority is imposed on those most vulnerable in society. However, they would assert that the majority viewpoint was guided by the underlying patriarchal system, and thus consisted of the Canadian male. This system would evaluate Oakes, not through the influence of the majority on restricting his individual liberty, but through a patriarchal lens that would always emphasize the dominant male perspective.

Unworkable Interference

As mentioned above, Mill holds that each individual is in the best position to determine his/her own needs. It follows that no person but Oakes should determine whether or not his personal drug use is in his best interests; only he can know that. This runs contrary to Natural Law theory, which finds that valid laws point us towards the common good, and accordingly that a law prohibiting drug possession would help redirect Oakes to the right path – the one leading to the common good. Mill would abhor such interference, pointing to autonomy as the core of human independence. Thus, he finds that interfering with one’s autonomy is akin to interfering with one’s humanity. In this light, s. 8 of the NCA is not simply a Charter violation, but a direct threat to Oakes’ humanity.

Dworkin would oppose Mill regarding this interference. He argues that Paternalism is justified when the alternative would be irreversible and destructive changes to that individual’s liberty. Thus, Dworkin would focus his analysis on whether or not Oakes’ drug use could cause such troubling changes to his liberty. If it could, he would justify s. 8’s interference based on possession. If not, he would side with Mill.

Significantly, Dworkin emphasizes the importance of proportionality between deprivation and restraint of liberty. This is a fine line that must be navigated with precision, lest an unwarranted intrusion on liberty results. This is directly analogous to the proportionality test inOakes, which requires the restriction of Charter principles be proportionate to the harm targeted by the relevant provision. Undoubtedly, Dworkin would support the Oakes Test in regard to the concern for tailoring the restricting provision to the perceived harm.Discussion-Motivated Reflection Critique

While our discussion on liberty and paternalism was lively, we struggled to incorporate other theories and initially could not explain this difficulty. It soon became apparent that this week’s theory, unlike previous perspectives, essentially included a dialogue between Mill and Dworkin, two proponents of a similar theory. Dworkin’s efforts produced a challenge to Mill’s approach, often via an expansion of his theory, while remaining within a similar scope. This reveals the constantly evolving nature of legal perspectives, and the efforts of generations of legal scholars to revise them in order to keep them relevant.

Law and Economics

The Theory of Law and Economics recognizes that governments enact laws that may or may not be efficient. The bulk of what they do is redistributive and, as such, almost any government action causes some to be better off at the expense of others. The Theory also recognizes that a well-crafted criminal law is an exception to this phenomenon. At first glance, it might be difficult to know if the Law and Economics Theorists would consider the reverse onus to be a “well-crafted” law. The key to answering this question would lie in whether or not the law is an instrument to achieve efficiency.

On the one hand, the Law and Economics Theorists would be opposed to the reverse onus, especially if they deemed the law to be one that imprisoned people arbitrarily. Not only is arbitrary imprisonment an unnecessary burden on taxpayers as a whole, but Law and Economic Theory supports liberty generally. This is because, according to the theory, liberty maximizes wealth.

On the other hand, if the Theorists agreed with Legislators that drug trafficking was a real and pressing danger which could be ameliorated by the reverse onus provision, they would see the benefit of such a law. The reason being that it would prevent the costly price society has to pay when drug traffickers are on the loose. One might claim that the Theorists would argue for the proliferation of the drug industry because, in essence, it is grounded in valuable transactions - both parties leave with something of more value to them than that which they had on arrival. However, the Theorists would foresee the tremendous cost of addiction and increased crime associated with drug gangs plus the toll this would have on society as a whole. The “externalities” in this case would seem to be far too costly for society to absorb. In this way, the gains of a small, underground portion of society would not outweigh the deleterious effects addiction and increased crime would heap on the larger population.

Regardless of whether the Theorists agree with the reverse onus provision, they would likely see the legislature, rather than the judiciary, as the key route to curbing the problem of drug trafficking. The Theorists believe that the role of judges is not redistributive. That is the role of the legislature. Redistribution (in the manner explained below) would likely be seen as an effective way to limit the trafficking problem.

The Law and Economics Theorists would have a unique way of analyzing the root cause of possession and trafficking crimes, which would have implications on the preferred remedy. The Theorists would likely posit that crime, or at least a large portion of crime, stems from poverty or an inability to engage in wealth maximization. This can be deduced from their assertion that a welfare system reduces crime. This is further supported by the Theorists’ argument that a strong wealth-maximizing and efficient system develops altruism in its citizens. If altruism is seen to negate the crime of theft, and a wealth-maximizing society can develop altruism where it did not exist, perhaps the theorist would argue that it could reduce criminal tendencies in individuals where they do exist.

Preferring to view individuals as economic and rational humans, the Law and Economic Theorists might claim that with the right opportunities afforded by welfare, Oakes would be able to engage in the wealth-maximization process. This would not only steer an individual away from criminal activity but would rather direct the individual to a life of efficiency. This would be an “optimal” alternative (to use the words of the Pareto-superiority model) as it would lead to a benefit not only for the criminal, but for society, as it would gain a productive, rational member. Based on this reasoning, a change enacted by the legislature affecting welfare would provide a far greater level of efficiency than Dickson’s decision in Oakes.

Making Connections

The ideas expressed by the Law and Economics Theorists would clash with those expressed by the Feminist Legal Theorists. Firstly, the concept of the “Rational Man” as a meta-theory describing the thinking and behaviour of all adult persons of sound mind, would be offensive to the sensibilities of a feminist who may choose to view all people as possessing a variety of different characteristics.

Even if the Law and Economics Theorists were to re-name their model the “rational person” the feminist theorist would argue that this change in nomenclature has the trapping of change but not the substance of it.

While the economist examines crimes by looking at the perpetrators of crimes, the feminist looks at the victims. This is likely why the two theories differ in their explanation of crime. Looking at the perpetrator causes the economists to believe that crimes are caused by poverty. Focusing on the victims leads the feminists to determine that, since majority of victims are women, crimes are caused by a proliferation of patriarchy and oppression of women. Robin Morgan famously stated that “pornography is the theory, rape is the practice”. It is the consistent objectification of women that leads to the crime of rape.

Discussion-Motivated Reflections and Critique

Posner’s Theory leaves no room for goodness and altruism spurred out of a sincere and selfless concern for others. According to his Theory, even altruism is an indirect form of self-interest. According to this perception, altruism is a moment in which an individual values the needs of society, of which the giver is part, as important to the overall success of the giver’s surrounding environment.

The Theory also falls short in citing poverty as the key motivator of crime. While poverty may be a factor in some crime, the Theory would likely not be able to explain the phenomena of wealthy, middle-aged, married women who begin shoplifting small items later in life. Nor could it explain spousal abuse in wealthy families. These crimes are not motivated by poverty and surely they could never be said to be in the self-interest of a spouse or his/her family.

While the Law and Economics Theory presents a convincing way to understand business transactions, escalating profits and efficiency in the marketplace. This Theory falls short in its estimation of human nature. Our group was left wanting more. Surely there is more to us as human beings than skin, bones and rational self-interest.

Feminist Jurisprudence

Challenges to Law

Feminist theories of law characterize several aspects of our legal system as falsehoods that are constructs of the patriarchy. Several of these challenges feminism makes can be found in the Oakes judgement. First, feminists say the separation of law from politics is impossible. There is certainly evidence of this at para 73: “The starting point… is… the nature of Parliament's interest or objective which accounts for the passage of s. 8 of the NCA. According to the Crown, s. 8 of the NCA is aimed at curbing drug trafficking by facilitating the conviction of drug traffickers…Parliament's concern that drug trafficking be decreased can be characterized as substantial and pressing” (Dickson C.J., para 73) In direct opposition to HLA Hart, feminist jurisprudence says that the separation of law from morality is impossible. The “Oakes Test” that comes out of this case does seem to contain some level of morality within it. The court spends a great deal of effort discussing underlying Charter values which feminists might argue are moral in essence. “The Court must be guided by the values and principles essential to a free and democratic society which I believe embody...commitment to social justice and equality… accommodation of a wide variety of beliefs… and faith in social and political institutions…[which are] the ultimate standard against which a limit on a right or freedom must be shown, despite its effect, to be reasonable and demonstrably justified.” (Dickson C.J. para 64) Feminists would say that these moral values are those belonging to the patriarchy. By looking to these moral elements as guiding principles the court is perpetuating the patriarchy, the power it has, and the disadvantages it creates.

Lon Fuller discussed the inner morality of law as a superior way of thinking. He said that if courts use judicial reasoning properly, such as the through application of the Oakes Test, they will get the “right”, just outcome. Feminism conversely, challenges this idea and would likely find the judicial reasoning in the Oakes Test as a way of advancing the positions of the powerful while pretending that what it is doing is reaching a fair outcome. Feminists would interpret the Oakes Test as promoting the patriarchy, while being disguised as reason and logic.

Catherine MacKinnon said the law is the “site and cloak of force” and that by adopting the male point of view and articulating it as “natural” and “right” the law makes male domination invisible. The male point of view is present throughout Oakes.

First, the so called ‘norms’ of judicial restraint and precedent are prevalent throughout Dickson C.J.’s analysis. He refers to many past cases and lower court interpretations of the meaning of S.8 of the NCA. He also looks to precedent for previous applications of S.1 Charter tests. MacKinnon would see each of these interpretations as further perpetuating the patriarchy and the values it seeks to enforce. MacKinnon’s interpretation of this would directly oppose Dworkin’s positivist view which said that the law provides the right answer in the application of principles of legal reasoning.

It is also notable that when applying the rational connection test to S.8 of the NCA the court repeatedly uses the term “rational”. “At a minimum, this requires that s. 8 be internally rational; there must be a rational connection between the basic fact of possession and the presumed fact of possession for the purpose of trafficking” (Dickson C.J. para 77) MacKinnon would say that what the court is doing is imposing the male point of view as to what qualifies as “rational” thus, this reinforces the patriarchy’s perspective and power.

Feminist Commendations

One element of this case the feminist perspective might approve of is the court’s consistent use of “he” and “she” together, rather than just male oriented terms. In this way the court gives equal acknowledgement to both men and women in the application of this judgement. On the other hand however, feminism challenges the “neutrality of law” and contends that it is simply a guise. Feminists say that in reality the law always takes the side of the more powerful (those who are alive with the patriarchy). In this way, perhaps many feminists would not buy into this use of “male” and “female” as having any measurable implications of equality.

At paragraph 70 the Dickson C.J. says, “[a]lthough the nature of the proportionality test will vary depending on the circumstances, in each case courts will be required to balance the interests of society with those of individuals and groups.” Post-Modernist Feminists might approve of this. They reject single solutions to issues of oppression and instead suggest that multiple solutions are required to respond to actual lives of actual people, rather than abstract ‘categories’ of people. The court’s balancing the societal interests with individual interests in this way is something French Feminists would see as positive.

The Judiciary

Out of the seven judge’s ruling on R. v. Oakes only one is female (Madame Justice Wilson). Relational Feminists would certainly take note of this. This perspective says that women’s socialization is different from men’s and thus it produces a different moral perspective, value and understanding (including the “ethics of care”). Relational feminist focus on women’s difference and would most likely say that having a more balanced male/female courtroom would better reflect these different woman perspectives in law. Relational feminists say incorporating ethics of care is of benefit to everyone, not just women and thus it would be positive for everyone to have a more equal female/male ratio in the courtroom.

Case Outcome

With respect to the finding in this case, the feminist perspective is unlikely to agree that the reverse onus in S.8 of the NCA should be found unconstitutional. The court finds S.8 to be an infringement on the Charter right to be presumed innocent. Feminists might see this as the court reinforcing the patriarchy by upholding this Charter value, which they see as a patriarchal value.

On one hand it is possible to conclude that a feminist would approve of the outcome here because it found in favour of a less powerful (those found guilty of possession of drugs). However, by overturning the reverse onus provision, the court actually made it more difficult for the male accused to be found guilty of trafficking. By putting the burden on the Crown rather than the male accused feminists would say the court is weighing in favour of the male and thus perpetuating the systematic and systemic domination by men.

Similarly, it is clear that the drug trade is a dangerous and often violent industry. Women are often the victims of violent crimes. As such, many feminists would see the reverse onus as something actually beneficial to women because it makes it more difficult for a male in a violent trade to be found innocent. In these ways it seems likely that the feminist perspective would not agree that the reverse onus provision should be overturned.

Discussion-Motivated Reflections and Critique

At first we struggled with the idea of applying feminist jurisprudence to a case involving a white male and drug possession. However, taking the core ideas from Feminist Theory and looking at R. v. Oakes through this lens helped us understand this case from a very different angle. So far in our law school careers, the things we know as the “principles of fundamental justice” have held the connotation that they are natural elements at the core of Canadian society, and somehow it seemed obvious that these would be underlying judicial analysis. The Feminist Theory changed our perspective on this. We were surprised by our ‘discovery’ that these values are actually “someone’s” values and that perhaps they are the values of the majority, used to further their power.

Critical Legal Studies and Critical Race Theory

Critical Legal Studies addresses the idea that our entire society is structured around maintaining and furthering power. At the same time as furthering the powerful, society is disempowering the people who do not have power and therefore asks the question: how does this law serve the interests of the powerful?

Minority groups in society are seen as less powerful than the dominant group – the white male . The critical legal studies perspective would see Oakes as fitting within a minority group as someone who is of lower socioeconomic status, which we can assume from the fact that he was on Worker’s Compensation. By having a reverse onus in s. 8 of the NCA, the minority (Oakes) is given the burden of disproving a presumption that he possessed narcotics for the purpose of trafficking based only on the fact that he was found in possession of narcotics. This reinforces the perpetuation of the dominant culture. From a Critical Legal Studies perspective, someone who is in possession of drugs would be outside the dominant culture and therefore, the power of the dominant culture is reaffirmed by relieving the dominant culture of the usual duty of proving a crime (i.e. intent to traffic).

Furthermore, on a first glance, the s. 1 Oakes Test appears to be a method that does not perpetuate the dominant culture since the test takes into account the balancing of objectives and infringements and requires minimal impairment on the accused’s rights. However, from a critical legal studies perspective, the Oakes Test allows the powerful to justify infringement on the rights of those who are less powerful than them. This is similar to the Legal Realist perspective in that personal characteristics, prejudices and temperaments of the judges come into play when ruling on a case. Critical Legal Studies, in assessing cases, would project these same things onto the case at hand to reaffirm the power of the dominant culture. For example, the Government clearly has more power than an individual on Worker’s Compensation, who has a small amount of narcotics in his possession and therefore, the Government would be projecting its characteristics, prejudices and temperaments onto the case at hand to come to a conclusion. In this example, the Oakes Test allows the perpetuation of the powerful by justifying the infringement of a right of a less powerful minority when it has already been established that that right is a core principle that is supposed to be protected for everyone, equally.

Over time, the Critical Legal Studies perspective has fragmented and diverse perspectives have emerged. One of these perspectives is Critical Race Theory. This theory emphasizes the importance of subjective accounts of racism and how by hearing people’s stories one can then understand them. Critical Race Theorists would take issue with the fact that Oakes’ situation was not considered or taken into account in this case. They would argue that it would have been beneficial for the Court to hear about Oakes’ history (i.e. WCB, the tough time he was presumably going through) and this would have given a better context to why Oakes, a member of a minority, was in the situation he was in.Making Connections

The perpetuation of the powerful is an idea that Feminist Legal Theorists would agree with. They would say the court is using the Oakes Test as a “cloak” to disguise the fact that they are really justifying the infringement by the powerful (the patriarchy) on the less powerful (women). Similarly, the powerful group that critical legal studies is concerned with is the dominant class of white males. Both perspectives are therefore addressing law as having males at the top of the hierarchy and the law serves the purpose of furthering their power.

The critical legal studies perspective has several similarities with Legal Realism as well. Both perspectives address the importance of the individual and their location in the structures of power. Specifically, the Legal Realists say that judges have significant discretion and they can use their power to make decisions. As a generalization, the majority of judges are white males and therefore this speaks to the power that the dominant culture (predominantly white males) have in the critical legal studies perspective.Discussion-Motivated Reflections and Critique

Our group discussed the possible application of the Critical Race Theory to Oakes, since on a first glance it does not seem to have a significant application in this case. We questioned the race of Oakes himself and had a difficult time trying to find the answer. We are still not certain at this point. From reading the case, there is no mention of Oakes’ race and we found this to be not only interesting, but relevant. It seems that when there is an absence of an explicit mention of an individual’s race, the “default” assumption is that the individual is Caucasian. We took some issue with this because it seems as though the idea of being Caucasian is not considered a defining feature, yet if one was African American their race could be seen as an identifying characteristic and thus, the social construct becomes incredibly powerful. The social construct of an African American’s race then becomes a characteristic that one feels must be mentioned in a case when describing the individual and what occurred.