Life Skills Development/Unit Three/Public Speaking/Lesson

Contents

Public speaking is talking to a group of people in a structured, deliberate manner intended to inform, influence, or entertain the listener’s.

In public speaking, as in any form of communication, there are five basic elements, often expressed as "who is saying what to whom utilizing what medium with what effects?"

|

QUESTION: Why is public speaking important? ANSWER: Many of you may think that if you are not a public figure mastering the art of public speaking is not important to you. However this is an erroneous perception as public speaking, will most certainly help you to succeed in anything you do. In just about every profitable position, some form of public speaking is required whether it be presenting to the board of directors, giving a group sales presentation, giving a report on a project, speaking to a committee, or just a group of peers. Public speaking is therefore an important part of how we communicate.

|

Some Facts About Public Speaking

Although public speaking has many similarities to everyday communication there are however some important differences.

- Public speaking is highly structured. It imposes strict time limitations on the speaker. In most cases the listeners are not allowed to interrupt with questions or commentary. Public speaking demands detailed planning and preparation.

- Public speaking requires the use of formal language. Slang, jargon, and bad grammar have little place in public speeches.

- Public speaking requires a formal method of delivery. Effective public speakers adjust their voices to be heard clearly throughout the audience. They assume an erect posture. They avoid distracting mannerisms and verbal habits.

The Speech Communication Process

Seven elements of the Speech Communication Process

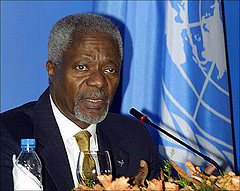

Speaker

Speech communication begins with a speaker. Your success as a speaker depends on you-on your personal credibility, your knowledge of the subject, your preparation of the speech, your manner of speaking, your sensitivity to the audience and the occasion. But successful speaking is more than a matter of technical skill. It also requires enthusiasm. You can’t expect people to be interested in what you say unless you are interested yourself.

Message

The message is whatever a speaker communicates to someone else. Your goal in public speaking is to have your intended message be the message that is actually communicated. Achieving this depends both on what you say (the verbal message) and on how you say it (the nonverbal message). Getting the verbal message just right requires work. Besides the message you send with words, you send a message with your tone of voice, appearance, gestures, facial expression, and eye contact. One of your jobs as a speaker is to make sure your nonverbal message does not distract from your verbal message.

Listener

The listener is the person who receives the communicated message. Everything a speaker says is filtered through a listener’s frame of reference i.e. the total of his or her knowledge, experience, goals, values, and attitudes. Because a speaker and a listener are different people, they can never have exactly the same frame of reference. And because a listener’s frame of reference can never be exactly the same as a speaker’s, the meaning of a message will never be exactly the same as to a speaker. Because people have different frames of reference, a public speaker must take great care to adapt the message to the particular audience being addressed. To be an effective speaker, you must be audience-centered. You must do everything in your speech with your audience in mind. You cannot assume that listeners will be interested in what you have to say. You must understand their point of view as you prepare the speech, and you must work to get them involved. You will quickly lose your listeners attention if your presentation is either too basic or too sophisticated. You will also lose your audience if you do not relate to their experience, interests, knowledge, and values.

Feedback

Feedback is important to let you know how your message is being received. There are various ways of assessing feedback. Do your listeners lean forward in their seats, as if paying close attention? Do they applaud in approval? Do they laugh at your jokes? Do they have quizzical looks on their faces? Do they shuffle their feet and gaze at the clock? The message sent by these reactions could be “I am fascinated,” “I am bored,” “I agree with you,” “I don’t agree with you,” or any number of others. As a speaker you need to be alert to these reactions and adjust your message accordingly.

Channel

The channel is the means by which the message is communicated. Public speakers may use one or more of several channels, each of which will affect the message received by the audience. Therefore it is important to utilize your medium well.

Interference

Interference is anything that impedes the communication of a message. Interference can be internal (comes from within your audience rather than from the outside) or external (from outside the building). As a speaker, you must try to hold your listeners’ attention despite these various kinds of interference.

Situation

The situation is the time and place in which speech communication occurs. Conversation always takes place in a certain situation. Public speakers must be alert to the situation. Certain occasions – funerals, religious services, graduation ceremonies- require certain kinds of speeches. Physical setting is also important. It makes a great deal of difference whether a speech is presented indoors or out, in a small classroom or in a gymnasium, to a densely packed crowd or to a handful of scattered souls. When you adjust to the situation of a public speech, you are only doing on a large scale what you do every day in conversation.

Assess Your Speechmaking Situation

Consider the occasion

How long will your talk last? Will you be the keynote speaker or one of many? Has your audience heard you before and what is their impression of you and your organization? Is this talk one of many or a single presentation?

To whom are you speaking?

As you begin your talk, it is imperative that you consider carefully your audience. What do they think about you? If you are representing a profession, agency, or organization, what does your audience think about that group?

Have you spoken to this audience in the past? If so, what did you learn about their needs and expectations? If this is a new group to you, how will you establish your rapport and your credibility? Aforementioned

When are you speaking?

Will you be the first in a long line of speakers? For symposium presentations, this is common. If you are the tenth of twenty speakers, you can imagine the fatigue that your audience might have.

Will you be the keynote speaker? You can expect that your host will introduce you to the audience. The emcee is expected to warm up the audience and to clarify the purpose of the occasion and to help you establish your credibility.

Another important aspect of public speaking is how long your talk lasts. Try to end your talk before your audience has stopped listening. Few audience members will complain that a speaker talked too briefly - more will complain that the speaker talked too long.

Where are you speaking?

The physical environment is important. Consider carefully the temperature, entrances and exits, and room configuration. What are your lighting requirements? If you plan to use a computer-generated and light projected presentation, you'll want to ensure that you have command of the lights and the equipment. Generally this requires a special trip to the scene for a dress rehearsal.

Why are you speaking?

What is the broad goal or purpose of your talk? Are you speaking to entertain, to persuade, or to inform? You'll want to be clear about your special purpose for talking as well. At the end of your talk, what do you expect your audience to believe, value, support, or do?

Communication experts George Grice and John Skinner suggest that you serve as mentor when you speak to inform; as advocate when you speak to persuade (to convince or to actuate) and as entertainer when you speak to amuse your audience. What are you speaking about? What is your topic for the presentation? Often, as a perceived expert on a subject, this is a part of your speaking request. Sometimes, you will be invited to talk about anything within your expertise.

Key Elements of Any Speech of Presentation

If you remember just one thing about public speaking remember this: have a point.

- Have an introduction, body, and conclusion. Follow the age-old advice, "Tell them what you are going to tell them, tell them, and then tell them what you told them." Most people find writing the body first is most helpful, then either the introduction or the conclusion.

- Define the task: Your goal. Decide on the parameters of your speech. What is your aim? What do you want to inform the audience about? What do you want to convince the audience about? What do you want to entertain the audience about?

- Avoid any apologetic statement at opening of speech – even if you were only asked to speak at the last minute – don’t mention this. Begin with aplomb! Use a dramatic and relevant quotation. Use a heart-rending experience. Sing a line or two from an appropriate calypso/ Quote relevant lines from a poem.

- Prepare. You cannot "over prepare". The better you know the material the more confident you will be when presenting and the more flowing the speech will sound.

- Language a) Work with words. Find the words that say exactly what you want to convey b) to gain an understanding of the function and uses of spoke word c) Avoid common mistakes in word use. Use Standard English grammar at all times, except when you are using a quotation in Trinidad or Tobago dialect for special emphasis. d) Let elegance be the guide and focus on vocabulary and the effectiveness of word choices.

- Vary the pace. Vary the pace at which you deliver the speech. Slow down, and then speed up. This will keep the listener's attention. Be careful not to talk too slowly or too quickly. Use your voice well.

- Have good eye contact. If you have been taught to look over the heads of those you are speaking to so you don’t feel nervous, forget it. Good eye contact means making a connection with your audience by looking them straight in the eyes. If the audience is small enough, try to make it a point to make eye contact with everyone.

- Use note cards not notepads. Notepads are bulky, noisy, and most of all, distracting. Use note cards for speeches. Never be afraid to use notes—even the best speakers rely on notes to ensure they communicate the points efficiently and effectively.

- Anticipate questions. Take the time to think about any question a listener may ask and formulate a positive answer that supports your presentation. It is OK to say you do not know the answer and tell the person you will get back to them if needed. The "I don't know" or "I can't say" answers are most effective when followed by "but I'll tell you what I do know..."

- Try to keep your speech under 20 minutes (if you are not given a specific time). Several studies have shown that 20 minutes is about the maximum amount of time listeners can stay attentive, after that, the attention levels begin to drop. Speaking is more stimulating than listening so although you may be excited to talk for longer, the chances are your listeners are ready for a break.

- Have a strong introduction and a strong conclusion. The introduction should be used to gain the attention of the listeners and persuade them to listen to your entire presentation. You are essentially selling them on why they should listen. Be sure you address their needs and not yours. The conclusion should consist of a powerful statement, quotation, anecdote, or other attention grabber. Never end a speech with, "that's all".

- Have a second conclusion prepared. After a speech or a presentation usually comes a question and answer period. Once the questions stop coming, it is best to end on a strong note. This is a great time to get your "last word" in.

- Act on every opportunity you can to speak. Anxiety of speaking is best subsided by experience.

- Support each main idea or issue with evidence - examples, illustrations, personal experiences, statistics, from your research and experience. Creative use of the material will build your presentation. Show information seeking strategies and tell where the information was found. Show relevance of information, of all your research by remembering to refer to the topic as you conclude each major point.

Developing Confidence as a Public Speaker

One of the major concerns of individuals in giving a speech is stage fright. Many people who converse easily in all kinds of everyday situations become frightened at the idea of standing up before a group to make a speech. Most people tend to be anxious before doing something important in public. Actors are nervous before a play, politicians are nervous before a campaign speech, athletes are nervous before a big game. It is perfectly normal to be nervous at the start of a speech however you must learn to use it to your advantage. This can be achieved through adequate preparation and positive thinking.

Here are some ways you can transform negative thoughts into positive:

Don’t Expect Perfection

It may also help you to know that there is no such thing as a perfect speech. At some point in every presentation, every speaker says or does something- no matter how minor-that does not come across exactly as he or she had planned. As you work on your speeches, make sure you prepare thoroughly and do all you can to get your message across to your listeners. But don’t panic about being perfect or about what will happen if you make a mistake. Once you free your mind of these burdens, you will find it much easier to approach your speeches with confidence and even with enthusiasm.

|

An excellent way to improve your vocal variety is to read aloud selections from poetry that require emphasis and feeling. Choose one of your favourite poems that falls into this category. Practice reading the selection aloud. As you read, use you voice to make the poem come alive. Vary your volume, rate, and pitch. Find the appropriate places for pauses. Underline the key words or phrases you think should be stressed. Modulate your tone of voice: use inflections for emphasis and meaning.

|

|

Role Play Role play provides the opportunity for you to develop and revise your understanding and perspectives by exploring thoughts and feelings of characters in given situations. Role play will help you to develop:

Before the Role Play The following describes a method of planning a role play:

|

|

1. Outline the tenets of effective public speaking that will assist in the preparation to speak about a topic selected from those below.

Ensure that these areas are taken int o consideration:

|

|

Assessing the presentation of the speech Gather a group of friends that will be willing to assist you in developing your Public Speaking Skills. Ensure that you have an even number fo persons to ensure that the activity runs smoothly.

JUDGING FORM (with criteria):

|

Portfolio Contents

- A copy of an audience analysis

- A copy of the preparation notes for speech; speech; summary notes to glance at during speech

- Reflections on the process and on delivery

- Observations made as team member during the group process of judging.

Checklists of Performance Task

1. Preparation of audience analysis

| RUBRIC of performance criteria | V. Well Done | Well Done | OK | Not Ok- Will redo by …. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | I considered the type and size of my audience. | ||||

| 2. | I gauged the audience’s knowledge of the subject. | ||||

| 3. | I took into account the sex, gender, age, background, etc. of my audience. | ||||

| 4. | I thought about where I would stand and whether I would be heard and seen clearly by all. | ||||

| 5. | I considered the needs of my audience as well as myself. |

| RUBRIC of performance criteria | V. Well Done | Well Done | OK | Not Ok- Will redo by …. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | I maintained eye contact with the audience | ||||

| 2. | I shared at least three points about the topic in a logical fashion | ||||

| 3. | I spoke for the given time | ||||

| 4. | I projected my voice and spoke in Standard English except when I intended to speak in the vernacular |