Introduction to Psychology 1/IPSY102/Intelligence/Bell curve

The results of intelligence tests follow the bell curve, a graph in the general shape of a bell. When the bell curve is used in psychological testing, the graph demonstrates a normal distribution of a trait, in this case, intelligence, in the human population. Many human traits naturally follow the bell curve. For example, if you lined up all your female schoolmates according to height, it is likely that a large cluster of them would be the average height for an American woman: 5’4”–5’6”. This cluster would fall in the centre of the bell curve, representing the average height for American women. There would be fewer women who stand closer to 4’11”. The same would be true for women of above-average height: those who stand closer to 5’11”. The trick to finding a bell curve in nature is to use a large sample size. Without a large sample size, it is less likely that the bell curve will represent the wider population. A representative sample is a subset of the population that accurately represents the general population. If, for example, you measured the height of the women in your classroom only, you might not actually have a representative sample. Perhaps the women’s basketball team wanted to take this course together, and they are all in your class. Because basketball players tend to be taller than average, the women in your class may not be a good representative sample of the population of American women. But if your sample included all the women at your school, it is likely that their heights would form a natural bell curve.

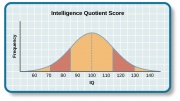

The same principles apply to intelligence tests scores. Individuals earn a score called an intelligence quotient (IQ). Over the years, different types of IQ tests have evolved, but the way scores are interpreted remains the same. The average IQ score on an IQ test is 100. Standard deviations describe how data are dispersed in a population and give context to large data sets. The bell curve uses the standard deviation to show how all scores are dispersed from the average score. In modern IQ testing, one standard deviation is 15 points. So a score of 85 would be described as “one standard deviation below the mean.” How would you describe a score of 115 and a score of 70? Any IQ score that falls within one standard deviation above and below the mean (between 85 and 115) is considered average, and 68% of the population has IQ scores in this range. An IQ score of 130 or above is considered a superior level.

Only 2.2% of the population has an IQ score below 70 (American Psychological Association [APA], 2013[1]). A score of 70 or below indicates significant cognitive delays, major deficits in adaptive functioning, and difficulty meeting “community standards of personal independence and social responsibility” when compared to same-aged peers (APA, 2013, p. 37[2]). An individual in this IQ range would be considered to have an intellectual disability and exhibit deficits in intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior (American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 2013[3]). Formerly known as mental retardation, the accepted term now is intellectual disability, and it has four subtypes: mild, moderate, severe, and profound. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Psychological Disorders lists criteria for each subgroup (APA, 2013[4]).

Characteristics of Cognitive Disorders Intellectual Disability Subtype Percentage of Intellectually Disabled Population Description Mild 85% 3rd- to 6th-grade skill level in reading, writing, and math; may be employed and live independently Moderate 10% Basic reading and writing skills; functional self-care skills; requires some oversight Severe 5% Functional self-care skills; requires oversight of daily environment and activities Profound <1% May be able to communicate verbally or nonverbally; requires intensive oversight

On the other end of the intelligence spectrum are those individuals whose IQs fall into the highest ranges. Consistent with the bell curve, about 2% of the population falls into this category. People are considered gifted if they have an IQ score of 130 or higher, or superior intelligence in a particular area. Long ago, popular belief suggested that people of high intelligence were maladjusted. This idea was disproven through a groundbreaking study of gifted children. In 1921, Lewis Terman began a longitudinal study of over 1500 children with IQs over 135 (Terman, 1925[5]). His findings showed that these children became well-educated, successful adults who were, in fact, well-adjusted (Terman & Oden, 1947[6]). Additionally, Terman’s study showed that the subjects were above average in physical build and attractiveness, dispelling an earlier popular notion that highly intelligent people were “weaklings.” Some people with very high IQs elect to join Mensa, an organization dedicated to identifying, researching, and fostering intelligence. Members must have an IQ score in the top 2% of the population, and they may be required to pass other exams in their application to join the group.

Dig deeper: What's in a name? Mental retardation

In the past, individuals with IQ scores below 70 and significant adaptive and social functioning delays were diagnosed with mental retardation. When this diagnosis was first named, the title held no social stigma. In time, however, the degrading word “retard” sprang from this diagnostic term. “Retard” was frequently used as a taunt, especially among young people, until the words “mentally retarded” and “retard” became an insult. As such, the DSM-5 now labels this diagnosis as “intellectual disability.” Many states once had a Department of Mental Retardation to serve those diagnosed with such cognitive delays, but most have changed their name to Department of Developmental Disabilities or something similar in language. The Social Security Administration still uses the term “mental retardation” but is considering eliminating it from its programming (Goad, 2013[7]). Earlier in the chapter, we discussed how language affects how we think. Do you think changing the title of this department has any impact on how people regard those with developmental disabilities? Does a different name give people more dignity, and if so, how? Does it change the expectations for those with developmental or cognitive disabilities? Why or why not?

References

- ↑ American Psychological Association. (2013). In Diagnostic and statistical manual of psychological disorders (5th ed., pp. 34–36). Washington, D. C.: American Psychological Association.

- ↑ American Psychological Association. (2013). In Diagnostic and statistical manual of psychological disorders (5th ed., pp. 34–36). Washington, D. C.: American Psychological Association.

- ↑ American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. (2013). Definition of intellectual disability. Retrieved from http://aaidd.org/intellectual-disability/definition#.UmkR2xD2Bh4

- ↑ American Psychological Association. (2013). In Diagnostic and statistical manual of psychological disorders (5th ed., pp. 34–36). Washington, D. C.: American Psychological Association.

- ↑ Terman, L. M. (1925). Mental and physical traits of a thousand gifted children (I). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- ↑ Terman, L. M., & Oden, M. H. (1947). The gifted child grows up: 25 years’ follow-up of a superior group: Genetic studies of genius (Vol. 4). Standord, CA: Stanford University Press.

- ↑ Goad, B. (2013, January 25). SSA wants to stop calling people 'mentally retarded.’ Retrieved from http://thehill.com/blogs/regwatch/pending-regs/279399-ssa-wants-to-stop-calling-people-mentally-retarded

- Source

- This page was proudly adapted from Psychology published by OpenStax CNX. Oct 31, 2016 under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/4abf04bf-93a0-45c3-9cbc-2cefd46e68cc@5.52.