Introduction to Psychology 1/IPSY101/Contemporary Psychology/Bio and evolutionary psychology

| “ | Evolution may seem like a historical concept that applies only to our ancient ancestors but, in truth, it is still very much a part of our modern daily lives. | ” |

| —David Buss | ||

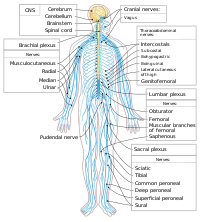

Biopsychology

As the name suggests, biopsychology explores how our biology influences our behaviour. While biological psychology is a broad field, many biological psychologists want to understand how the structure and function of the nervous system is related to behaviour. As such, they often combine the research strategies of both psychologists and physiologists to accomplish this goal (as discussed in Carlson, 2013[1]).

The research interests of biological psychologists span a number of domains, including but not limited to, sensory and motor systems, sleep, drug use and abuse, ingestive behaviour, reproductive behaviour, neurodevelopment, plasticity of the nervous system, and biological correlates of psychological disorders. Given the broad areas of interest falling under the purview of biological psychology, it will probably come as no surprise that individuals from all sorts of backgrounds are involved in this research, including biologists, medical professionals, physiologists, and chemists. This interdisciplinary approach is often referred to as neuroscience, of which biological psychology is a component (Carlson, 2013).

Evolutionary psychology

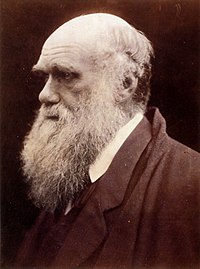

While biopsychology typically focuses on the immediate causes of behaviour based in the physiology of a human or other animal, evolutionary psychology seeks to study the ultimate biological causes of behaviour. To the extent that a behaviour is impacted by genetics, a behaviour, like any anatomical characteristic of a human or animal, will demonstrate adaption to its surroundings. These surroundings include the physical environment and, since interactions between organisms can be important to survival and reproduction, the social environment. The study of behaviour in the context of evolution has its origins with Charles Darwin, the co-discoverer of the theory of evolution by natural selection. Darwin was well aware that behaviours should be adaptive and wrote books titled, The Descent of Man (1871[2]) and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872[3]), to explore this field.Evolutionary psychology, and specifically, the evolutionary psychology of humans, has enjoyed a resurgence in recent decades. To be subject to evolution by natural selection, a behaviour must have a significant genetic cause. In general, we expect all human cultures to express a behaviour if it is caused genetically, since the genetic differences among human groups are small. The approach taken by most evolutionary psychologists is to predict the outcome of a behaviour in a particular situation based on evolutionary theory and then to make observations, or conduct experiments, to determine whether the results match the theory. It is important to recognize that these types of studies are not strong evidence that a behaviour is adaptive, since they lack information that the behaviour is in some part genetic and not entirely cultural (Endler, 1986[4]). Demonstrating that a trait, especially in humans, is naturally selected is extraordinarily difficult; perhaps for this reason, some evolutionary psychologists are content to assume the behaviours they study have genetic determinants (Confer et al., 2010[5]).

One other drawback of evolutionary psychology is that the traits that we possess now evolved under environmental and social conditions far back in human history, and we have a poor understanding of what these conditions were. This makes predictions about what is adaptive for a behaviour difficult. Behavioural traits need not be adaptive under current conditions, only under the conditions of the past when they evolved, about which we can only hypothesize.

There are many areas of human behaviour for which evolution can make predictions. Examples include memory, mate choice, relationships between kin, friendship and cooperation, parenting, social organization, and status (Confer et al., 2010).

Evolutionary psychologists have had success in finding experimental correspondence between observations and expectations. In one example, in a study of mate preference differences between men and women that spanned 37 cultures, Buss (1989[6]) found that, in line with the predictions of evolution, women valued earning potential factors greater than men, and men valued potential reproductive factors (youth and attractiveness) greater than women in their prospective mates.

It is worth noting, however, that more recent research has shown that mate preferences such as these with presumed evolutionary roots decline proportionally to increases in nations' gender parity (Zentner & Mitura, 2012[7]).

Sensation and Perception

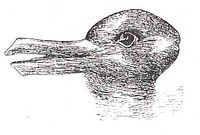

Scientists interested in both physiological aspects of sensory systems as well as in the psychological experience of sensory information work within the area of sensation and perception. As such, sensation and perception research is also quite interdisciplinary. Imagine walking between buildings as you move from one class to another. You are inundated with sights, sounds, touch sensations, and smells. You also experience the temperature of the air around you and maintain your balance as you make your way. These are all factors of interest to someone working in the domain of sensation and perception.

As described in a later chapter that focuses on the results of studies in sensation and perception, our experience of our world is not as simple as the sum total of all of the sensory information (or sensations) together. Rather, our experience (or perception) is complex and is influenced by where we focus our attention, our previous experiences, and even our cultural backgrounds.

References

- ↑ Carlson, N. R. (2013). Physiology of Behavior (11th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

- ↑ Darwin, C. (1871). The descent of man and selection in relation to sex. London: John Murray.

- ↑ Darwin, C. (1872). The expression of the emotions in man and animals. London: John Murray.

- ↑ Endler, J. A. (1986). Natural Selection in the Wild. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Confer, J. C., Easton, J. A., Fleischman, D. S., Goetz, C. D., Lewis, D. M. G., Perilloux, C., & Buss, D. M. (2010). Evolutionary psychology. Controversies, questions, prospects, and limitations. American Psychologist, 65, 100–126.

- ↑ Buss, D. M. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 12, 1–49.

- ↑ Zentner, M. & Mitura. K. (2012). Stepping out of the caveman's shadow: nations' gender gap predicts degree of sex differentiation in mate preferences. Psychological Science, 23(10), 1176-1185.

- Source

- This page was proudly adapted from Psychology published by OpenStax CNX. Oct 31, 2016 under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/4abf04bf-93a0-45c3-9cbc-2cefd46e68cc@5.52.