Introduction TO MALARIA

MALARIA PREVENTION, MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL INTRODUCTION TO THE COURSE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

AMREF would like to acknowledge the contribution of the Commonwealth of Learning, whose financial assistance made the development of this course possible.

AMREF is also grateful to the team from the Division of Malaria Control in the Ministry of Health who participated in the production of this course. The members of this team were Dr. Beth Rapuoda, Dr. A. Manya, Dr. R. Kiptui, Dr. K. Njagi, Dr. D. Alusala, Dr. D. Memusi, J. Moro, J. Sang, M. Wanga, P. Kiptoo, B. Mageto; and Dr Ben Midia from Kenyatta National Hospital.

Thank you very much!

Introduction

Welcome to the Distance Learning Course on Malaria. In this section we are going to give you background information on malaria and its control. This background information is of great importance because it gives the magnitude of the problem and the relevance of this course in the fight against Malaria. You shall also learn how this course is organized, for whom and how to go through it.

It is highly recommended that you go through this section before reading the rest of the units in this course.

Background Information

Malaria remains a major public health problem in the world, especially in countries in the tropics

Morbidity and mortality in the general population remains very significant. According to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, 300–500 million (WHO1) clinical malaria cases are reported every year. Of this, over 100 million people develop severe disease while 100 million people and more die from it. About 80% of the cases and more than 95% of the deaths occur in tropical Africa.

An estimated 280 million people are carriers of the malaria parasite and the situation is getting worse all the time.

Resistance of malaria parasites to drugs is steadily gaining new ground and fresh outbreaks of malaria are being reported from areas which were hardly affected before.

According to the statistics of the United Nations Population Division in 1990, malaria is the only disease today (apart from HIV/AIDS) that shows a significant rising tendency. Malaria epidemics are now frequent and spread to areas previously without epidemics. Unfortunately, the greatest challenge faced by communities is to address the issue of poverty and malaria.

The malaria epidemic is like loading up seven Boeing 747 airliners each day, then deliberately crashing them into Mt. Kilimanjaro”

Dr Wenceslaus Kilama, Chairman Malaria Foundation International

The United Nations has come up with several initiatives to address the issue of poverty and malaria. In the year 2000, 189 countries adopted the UN declaration on Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). MDGs consist of 8 Goals of which 4 are health related. Under the guidance of the MDGs, UN Member States have pledged that by 2015 they will:

|

'The Linkage between Government’s Commitment, Malaria Burden, Poverty and Economic Development '

Malaria is a burden to governments and many rural communities. Over 20 per cent of the world’s population is affected by this well known and deadly disease. Humanitarian crisis and population movements have led to excessive suffering and death. In much of the world, especially in tropical Africa, continuous malaria transmission leads to hundreds of thousands of child deaths each year. This overwhelms national health services, sustains poverty and disempowers societies.

Several countries have established effective malaria control programmes leading to reduced malaria burden of the communities.

- The management of clinical attacks of malaria costs households more than US$20 per year. Subsequently governments have solicited for support from development partners to implement new drug policies which are channelled free of charge through health facilities in some countries.

- Leading foreign exchange earners such as tourism are threatened by malaria, because tourists visit malaria endemic areas. For example, the first case of chloroquine resistance in Kenya was detected in a tourist in 1979;

- Developmental projects in agriculture experience setbacks due to creation of suitable mosquito breeding sites, such as in irrigation schemes.

WHO initiated a series of meetings of experts to formulate solutions to the problem of malaria, focusing especially on Africa, the Americas and Asia.

On realizing that the suffering caused by malaria and the worsening trend of the situation was now a global crisis, a global malaria control strategy was initiated, based on recommendations made by members from 82 malaria countries. The global strategy which is known as Roll Back Malaria (RBM) was launched in 1998. RBM is a worldwide partnership which works to halve the burden of malaria by 2010.

The Global RBM strategy has the following objectives:

- To prevent malaria mortality;

- To reduce morbidity;

- To reduce social and economic loss due to malaria.

The six technical elements of the RBM strategy are:

- Evidence-based decisions using surveillance, appropriate response and building community awareness;

- Multiple prevention using insecticide-treated nets, environmental management to control mosquitoes and making pregnancy safer;

- Rapid diagnosis and treatment supporting home care, direct access to effective medicines and wide availability of health services;

- Focused research to develop new medicines, vaccines and safe insecticides;

- Well-coordinated action for strengthening existing health services, policies and providing technical support;

- Harmonized action to build a dynamic global movement.

To implement the above objectives using the strategies mentioned, the regional strategy (RBM) approach adopted the following four (4) components:

- Assuring access to good management of malaria disease (including early diagnosis, prompt and effective treatment and referral);

- Selective and sustainable vector control measures (e.g. use of insecticide treated materials) and in the recent years the Long Lasting Insecticide Nets (LLINs);

- Prevention and control of epidemics;

- Regular re-assessment of country’s malaria situation, in particular the ecological, social and economic determinants of the disease.

|

The challenge is on each country to adopt the above components according to their local situation, available health infrastructure, existing control operations, available resources and technical expertise. |

Political Commitment to Malaria Control and the Development of the Health Sector Strategic Plan (HSSP)

Poverty is one of the key obstacles to fighting malaria. The Poverty Reduction Strategic Paper aims to “ to enhance equity, quality, accessibility and affordability of health care through better targeting of resource to the poor – geographically and technically – and more efficient use of resources” (PRSP 2001).

Regional governments have identified malaria control as one of the six essential packages within the Health Strategic Plan. As a sign of political commitment to fighting malaria the following are being implemented:

- National Malaria Control Programmes have been established within each Ministry of Health since 2001 to strengthen the reforms targeted against the national disease priorities;

- The targets of the National Malaria Strategies developed have been harmonized in line with international RBM targets agreed upon at the Abuja Summit in 2000.

The malaria situation in the rest of Africa is not any better. Available data indicate that malaria is the most prevalent disease in all other parts of Africa and it is also among the top five (5) causes of morbidity and mortality. All age groups are affected, but the most serious impact is borne by children under five (5) years of age.

In Africa malaria accounts for 25–30% of hospital outpatient attendance resulting in 9-20% of hospital admissions and upto 9-14% of inpatient death. Some high altitude districts are malaria epidemic prone. The number of districts affected may vary from one country to another. An example of the magnitude of the problem can be seen by the following statistics from Kenya which highlights the burden of malaria.

|

The Burden of Malaria in Kenya (NMS 2001)

|

The prevalence of malaria is usually determined by the parasite rate among children aged under 10 years and it varies regionally in each country. The example in Kenya shows that the prevalence can be classified into the following four categories:

• Highly endemic or stable malaria. This situation occurs in the lowlands (300m) and is characterized by transmission taking place for more than six months in a year. The burden of disease is on children under five years and pregnant women. This is because children under 5 years have not yet developed immunity, while during pregnancy immunity is partially depressed. Examples of such areas include the coastal strip and Lake Victoria areas of Kenya.

• Seasonal or unstable malaria. This situation occurs at altitudes between 300–700m and is characterized by transmission taking place during the rains for three months. The burden of disease is on all age groups.

• Epidemic prone areas. This situation occurs at altitude ranging between 1700–2500m and is characterized by transmission taking place during and after the rains for 1 – 3 months. All age groups are affected. In Kenya 16 districts have been identified to be prone to epidemics. They include Kericho, Buret, Bomet, Nandi South, Nandi North, Uasin Gishu, Koibatek, Trans Nzoia, Trans Mara, Narok, Mt. Elgon and West Pokot in the Rift Valley, Kisii, Gucha and Nyamira in the highlands of Nyanza Province and Lugari in Western Province. In Uganda the districts affected by epidemics are Kabale, Rukungiri and Kapchorwa. You can also mention the number of districts affected by malaria epidemics in your country.

• Malaria free Zone. Very few areas in Africa are malaria free. They occur at altitudes above 2500m and there is no active transmission. Cases reported are imported from endemic areas. An example is the slopes of Mount Kenya.

I hope your answer included the following impact of Malaria on our socio-economic sector::

- Absenteeism from work and/or school;

- Costly treatment for the disease;

- Massive financing of workshops, training and support to malaria programmes;

- he big budget allocations given for attention of malaria in national budget and hospital budgets;

- The work load in hospitals due to malaria.

The other problem is related to Malaria treatment practices. How is that? Well as you know we health workers as well as the general public have adopted treatment practices that fuel the malaria crisis instead of ending it. These include the following:

- The widespread use of incorrect antimalarials by the public and some health workers;

- The rampant habit of self-medication without justification;

- Increase in the abuse of antimalarials through indiscriminate use, incorrect dosing and self-medication.

|

If the above serious trend is allowed to continue unchecked, it could easily enhance the emergence and spread of multiple drug resistant strains of P. falciparum with all the accompanying grave consequences. |

Why take this course?

This course was designed in order to equip you with the knowledge, skills and right attitudes to fight malaria. In particular, it was intended to:

- Provide health workers at different levels of health care service with knowledge, skills, practice and attitudes on malaria prevention and control through self-guided/tutored materials on malaria;

- Provide you with a quick reference for use at your place of work so that you can effect prompt diagnosis, appropriate treatment and/or referral of malaria cases;

- To provide you with simple diagnostic and treatment guidelines which you can internalize through self-guided learning.

Why the Health Worker

As a health worker, you are a part of the big team which we call the Ministry of Health. You undertake important and indispensable activities through your service to the community. Some of these activities are to manage, control and prevent malaria. We hope that this course will prepare you efficiently and accurately to undertake the following task:

- Treat uncomplicated malaria appropriately and promptly;

- Treat all children and pregnant mothers with fever for malaria;

- Recognise the signs of severe Malaria and how to treat and/or refer appropriately;

- Identify and treat Malaria during pregnancy appropriately;

- Encourage pregnant mothers and children to sleep under insecticide treated nets;

- Carry out health education and counselling on Malaria;

- Be accountable to the community you serve.

As you can see from these tasks, you are an important partner in the noble cause of “rolling back malaria”. One way of ensuring you perform these tasks properly and provide quality health care is through a course such as this one. The material in this course is meant to compliment and not substitute the knowledge and experience you continue to gather from ongoing national, regional and local activities on malaria.

Target Audience

This course targets the following cadres of health professionals:

- Medical Doctors.

- Clinical Officers.

- Midwives.

- Nurses.

- Other allied health professionals.

- Laboratory Technicians and Technologists.

- Pharmacy Technicians/Dispensers.

- Pharmacists.

- Parasitological Officers

- Entomological Officers.

- Environmental health Officers/Assistants.

The other cadres who should benefit from this course and are not necessarily health professionals are the Nurse Aides and Nurse Assistants.

Objectives of the Course

By the end of this course you should be able to:

- Describe the magnitude of malaria globally, in the African region, and in your community;

- Describe the presentation of Malaria;

- Describe the diagnosis of Malaria;

- Explain the management of Malaria;

- Explain the interaction of HIV/AIDS with Malaria;

- Prevent and reduce incidence, complications and death due to Malaria;

- Detect, prevent and rapidly control epidemics;

- Prevent Malaria;

- Provide Health Educate and counselling to the communities;

- Carry out disease surveillance with respect to Malaria.

Course Content

The units are tailored to have specific learning objectives and the following is the course outline:

- UNIT 1. About Malaria

- UNIT 2. Clinical Assessment of Malaria.

- UNIT 3. Severe and complicated Malaria.

- UNIT 4. Treatment of Malaria.

- UNIT 5. Treatment defaults in Malaria.

- UNIT 6. Referral in Severe and Complicated Malaria.

- UNIT 7. Malaria in Pregnancy.

- UNIT 8. Prevention and Control of Malaria.

- UNIT 9. Community Based Management of fever and Malaria in children.

- UNIT 10. HIV/AIDS and Malaria.

- UNIT 11. Counselling and Health Education on Malaria.

- UNIT 12. Malaria Surveillance.

Course Materials

The course comprises of 12 booklets. Each booklet has a studyguide and assignment. There is no accompanying reference textbook.

How to go through the Course

• Duration of the course;

One advantage of a distance education course such as this one is that it allows you to work at your own time and pace. However, If you work consistently and complete your lessons and assignments without any delay, it will take you a minimum of 8 months to complete this course.

• Getting started and working on your course.

Once we accept your application for this course, we shall send you the course introduction, a pretest and the first three units of this course. You should start by doing the Pretest. Try to answer all the questions in the pretest. It is designed to evaluate our material/teaching rather than to test you. When you complete the pretest, go through the course introduction first and then proceed to go through the Units, starting with Unit 1. As you go through each unit, read it thoroughly and do all the in-text activities. In-text activities are designed to help you check your understanding as you go along. When you feel confident that you have learnt the work of the unit, complete the assignment and send it back to us for marking. Do not forget to post the pretest. They will be marked and returned to you together with the next lessons. This will continue until you complete the last unit and do the Post-test.

• How to make the most of this course.

It is important to remember that you cannot learn all about malaria from one course. Although we learn a lot of things from books and courses, we learn even more from our patients -- from listening carefully to their story and from observing their appearance and behavior. While a book can describe general symptoms and signs of a disease, a patient can tell you in great detail about what he feels; and your observations of the patient will show you the clinical signs. That is how patients teach us about illness.

After you complete each unit in this course, try to apply what you have learned in the lesson to your day-to-day clinical work. Listen carefully to the patients who come to you, and see if they describe symptoms you have read about. Use the knowledge you have gained from this course to ask patients about other symptoms they may have forgotten to mention.

Share your new knowledge with your co-workers by discussing malaria cases with other members of the staff; presenting your findings, explaining the significance of those findings, and asking for their opinions. In that way, the patient will benefit from other insights, and your co-workers will also refresh their knowledge too.

Remember, the real objective of this course is to help you give better care to your patients -- to diagnose malaria more accurately and to treat it appropriately. So use what you learn in this course to improve your clinical work.

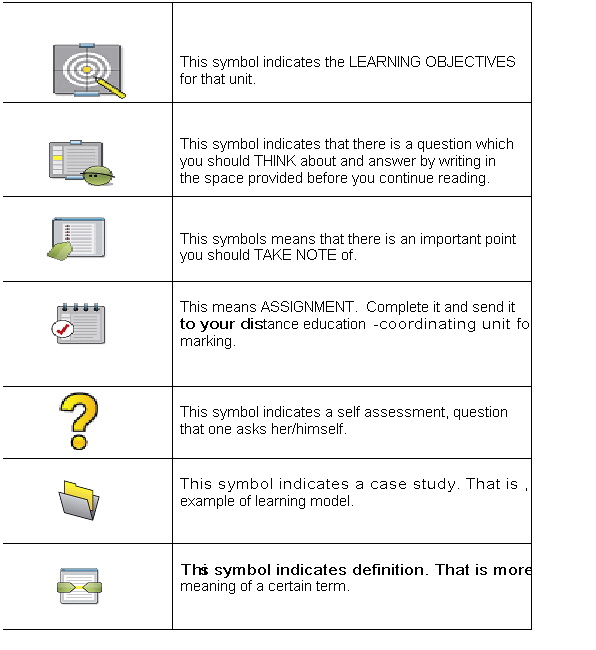

Symbols used in the course

This symbol indicates the LEARNING OBJECTIVES for that unit.

.

Limitations of the Course

Although the writers of this course have done their best to give you the most current information, the dynamic nature of malaria case management means that changes are taking place all the time. You will therefore need to be on the look out for new information on malaria from time to time to supplement the one given in this course.

If you find some parts of this course a little advanced write to your tutor for assistance.

Welcome to the course!