Human earth shapers/ETHS101/Ecology and Evolution/Mass Extinctions

Mass Extinctions

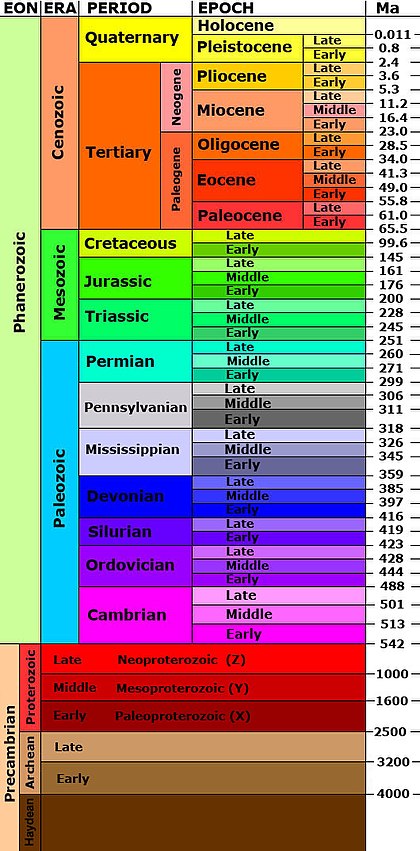

In this Learning Pathway, we learn that extinction is one path of evolution. It is normal - extinctions have been happening throughout time. The fossil record tells us that life has diversified since complex organisms first evolved some 600 million years ago. But over that time life has been through the nexus of five major mass extinction events and several smaller ones. We also look at what a mass extinction is and examine two case studies: the 'Great Dying' at the end of the Permian (252 million years ago) and the iconic demise of the Dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous 66 million years ago.

Extinction is a normal part of evolution. When species are exposed to conditions (including the presence of competitors, predators and pathogens) beyond their tolerances, are unable to move anywhere that suits them and cannot evolve fast enough they will become extinct.

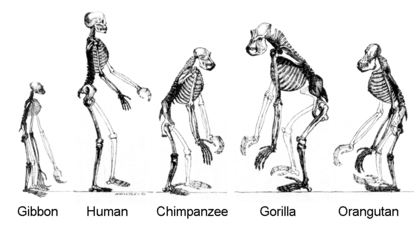

- Humans or Homo sapiens are the only Hominid to still exist. Over the last 5 million years of evolution of this family, there have been rapid changes and experiments that did not continue. Anatomically modern humans are the only group to be extant (still around) and the many other branches of the human family tree are extinct.

- This will take to you to an Interactive human family tree. The site will help you explore the different human-like species that didn't evolve fast enough.

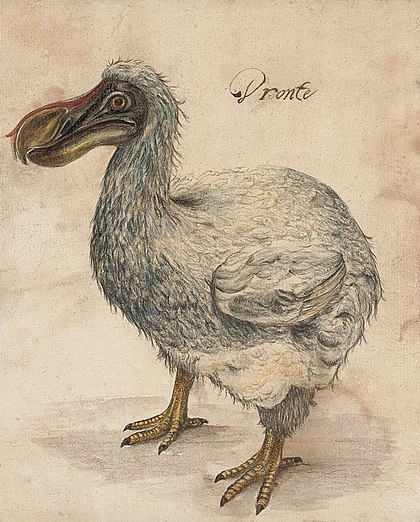

- Island inhabitants are vulnerable to extinction. Dodos were once abundant on the Island of Mauritius. They were first described by European sailors in the late 1500s. The birds were painted, written about, collected and hunted for food. Within 60 years they were extinct. Humans caused the extinction of the dodos, birds which are now synonymous with extinction.

Extinctions at scale

In his curve of life, John Phillips recognised that there were times when the fossil record became sparse. These times are co-incident with the disappearance of many different forms of life in a relatively short span of geological time. We call the largest of these events mass extinctions.

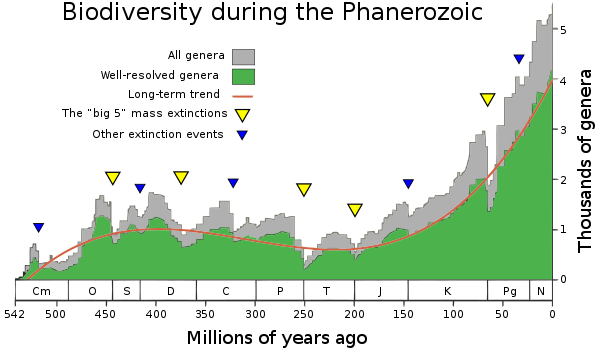

The graph below depicts thousands of marine genera plotted through geological time. It is apparent that the number of genera is increasing through time. This may partially be an artefact of fossil preservation, which is better in more recent successions. The graph is based on a compendium of fossil data from nearly 300 locations that included 36,380 genera made by J. Sepkoski (2002).

Importantly, the graph also shows times when the number of genera dropped dramatically. The largest drops are arrowed in yellow and others are in blue. The drops marked with yellow arrows are the five major mass extinction events. Because of the change in fossil types across these time spans, they also coincide with major geological period or era boundaries.

5 Major Mass Extinctions

- End of the Ordovician Period

- End of the Devonian Period

- End of the Permian Period

- End of the Triassic Period

- End of the Cretaceous Period

After each major mass extinction event there have been "reef gaps": where it has taken many millions of years before reefs come back. Recently it has been suggested that reefs have come back more rapidly than first thought after the Permian mass extinction event, but these reefs were dominated by sponges - not coral. In fact this mass extinction wiped out all the older coral forms and it was not until some 10 million years later that a new form of coral evolved and reefs began to reappear in the fossil record.

- Disaster Taxa and Recovery

- A mass extinction may be marked by the abundance of a few resilient groups. These are called disaster taxa. Over time as the environment becomes more stable and favourable for life new opportunities arise for new species to evolve.