How art speaks/ART103/Iconography

From WikiEducator

Jump to: navigation, search

Introduction to Iconography

At the simplest of levels, iconography is the containment of deeper meanings in simple representations. It makes use of symbolism to generate narrative, which in turn develops a work’s meaning. Each of the objects in the Arnolfini Portrait shown above has a specific meaning beyond their imagery. In fact, this painting is actually a painted marriage contract designed to solidify the agreement between these two families. It is especially important to remember that this is not a painting of an actual scene, but a constructed image to say specific things.

- You notice that the bride is pregnant. She wasn't at the time of the painting but this is a symbolic act to represent that she will become fruitful.

- The little dog at her feet is a symbol of fidelity, and is often seen with portraits of women paid for by their husbands.

- The discarded shoes are often a symbol of the sanctity of marriage.

- The single candle lit in the daylight (look at the chandelier) is a symbol of the bridal candle, a devotional candle that was to burn all night the first night of the marriage.

- The chair back has a carving of St. Margaret, the patron saint of childbirth.

- The orange on the windowsill and the rich clothing are symbols of future material wealth (in 1434 oranges were hand carried from India and very expensive).

- The circular mirror at the back reflects both the artist and another man, and the artist's signature says "Jan van Eyck was present", both examples of witnesses for the betrothal pictured. (At the time, a promise to marry was a legal contract).

- The circular forms around the mirror are tiny paintings of the Stations of the Cross.

Iconography in art

For another similar discussion of iconography in art, view and listen to art historians talk about Robert Campin’s Mérode Alterpiece.

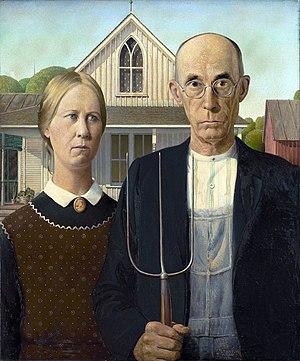

You can see how densely populated iconography in imagery can convey specific hidden meanings. The problem here is to know what all of this means if we want to understand the work. Another more contemporary painting with many icons embedded in it is Grant Wood’s American Gothic from the 1930’s. The dour expressions on the figures’ faces signify the toughness of a Midwestern American farm couple. Indeed, one critic complained that the woman in the painting had a “face that could sour milk”. Notice how the trees and bushes in the painting’s background and the small cameo the woman wears mirror the soft roundness of her face: these traditional symbols of femininity carry throughout the work. In contrast, the man’s straight-backed stance is reflected in the pitchfork he holds, and again in the window frames on the house behind him. Even the stitching on his overalls mimics the form of the pitchfork. The arched window frame at the top center of the painting in particular is a symbol of the gothic architecture style from 12th century Europe.

The armor, weapons and medals show a focus on military accomplishments. The open book alludes to knowledge and in this case, the drawing of a canon mirrors the overall theme. The globe is a symbol of both travel and our common existence as earth-bound beings. Contemporary vanitas paintings could certainly include allusions to air and space travel. On the far right of the work, behind the book and in the shadows, lies a skull, again reminding us of the shortness of life and the inevitability of death.

We can use iconography to find meaning in artworks from popular culture too.