The Northern Wars (1845)

| [▲]The New Zealand Wars | ||

|---|---|---|

| The Northern Wars (1845-46) | Introduction | Kororareka | Puketutu | Te Ahuahu | Ohaeawai | Ruapekapeka | |

Contents

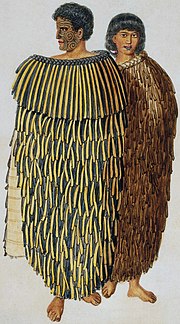

[hide]Introduction

Despite (or perhaps because of) Northland's importance in the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi it was also the location of the first significant conflict between Maori and pakeha. Many of the large personalities who stride through New Zealand history do so from the Northern Wars: Hone Heke, Governor George Grey, Tamati Waka Nene, Henry and William Williams. Militarily, the Northern Wars were not successful for the europeans: Heke (despite being wounded at Te Ahuahu) and Kawiti led troops on a merry dance through the New Zealand bush, forcing the British soldiers to drag cumbersome artillery to one position, before abandoning it in favour of another.

Kororareka (11th-12th March 1845)

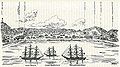

- Images from the siege of Kororareka, 1845

“…God made this country for us. It cannot be sliced; if it were a whale it might be sliced. Do you return to your own country, which was made by God for you. God made this land for us; it is not for any stranger or foreign nation to meddle with this sacred country.”—Hone Heke's letter to the Governor, 1845. [1] Heke's action of cutting down the flagstaff is one of the most memorable of New Zealand history, and rightly so: the sacking of Kororareka sent such a signal to the fledgling government about who actually controlled the country that they were forced to take up arms to try to exert some form of control over the 'natives'. Hone Heke had been the first Maori to sign the Treaty of Waitangi but his support for the European presence in the Bay of Islands was tested by indiscretions such as pakeha 'using timber from tapu (sacred) ground' [2]. Heke saw the Union Jack flying above the Bay of Islands as an assertion of pakeha sovereignty, so decided to cut it down on 8th July 1844. Following the flagstaff's resurrection, he repeated the act once on 18th January then again later in 1845. The sack of Kororareka (modern-day Russell) occurred on 11 March 1845, when Heke cut down the flagpole for a fourth time. Sporadic hostilities between pakeha and Maori turned into open warfare with Europeans hiding in the church and fleeing to ships in the harbour to escape the fighting.

- The Northern Wars

Puketutu (8th May 1845)

Following the sack of Kororareka, the British pursued Heke into the bush inland from the Bay of Islands. Hauling heavy artillery and equipment through the Northland bush, the British arrived at Puketutu pa on the 6th March 1845. They attacked the pa on the 8th but failed to take it. They were attacked on one flank by Kawiti's warriors, then immediately on the other by Hekes'. Lieutenant-General Hulme was forced to retreat, leaving dead and dying men on the battlefield. Puketutu was a confidence boost for the Maori and followed hard on their sack of Kororareka.

Te Ahuahu (12th June 1845)

After the battle at Puketutu, Heke returned to an older fortification at a place called Te Ahuahu. While he was out of the pa finding cattle for food, a pro-Government chief called Te Taonui captured the fortification. Upon his return, Heke fought Taonui and Tamati Waka Nene outside the pa but was defeated and wounded. Belich calls Te Ahuahu 'The forgotten battle'[3]

Ohaeawai (23rd June 1845)

- The Northern Wars

Frustrated by their loss at Puketutu and by their absence from the battle of Te Ahuahu, the British arrived at Ohaeawai on the 23rd June keen to defeat Heke. They proceeded to bombard the pa for a week, although this had little effect on the defenders who were able to stay in underground bunkers. Whenever an attack threatened, they were able to defend the pa by firing out of loopholes in the heavily fortified palisades. Flax was again employed to dampen the effect of muskets fire on the walls of the stockade. Despard's growing frustration eventually got the better of him and he ordered an attack on the pa on the 1st July 1845. In a few minutes, the British lost 40 men with 70 wounded. It ranks up with Gate Pa and Puketakauere as one of the worst British defeats in the New Zealand wars.

Ruapekapeka (31st December 1845-11th January 1846)

Once again British troops found themselves dragging heavy artillery through the New Zealand bush, this time towards Ruapekapeka. Governor Grey himself was present during the bombardment, having traveled from Auckland. British artillery scored a direct hit on the larger of Kawiti's two cannon, as well as achieving a breach of the pallisade wall surrounding the pa. When the British eventually entered the fortress on 11 January 1845, they found it abandoned. Maori drew the British into the surrounding bush in an attempted ambush and succeeded in killing 12 and wounding 30. The battle is notable for the bunkers and trenches that Maori dug in order to protect themselves from the European artillery. Belich holds that this tactic prefigures the trench warfare of the Crimean and Great Wars by a number of decades, and is testament to Maori prowess in battle. Ruapekapeka was the third loss for the British in four battles in Northland, and is also notable for the military skill Maori employed in bringing about that defeat.

- Images from the The battle of Ruapekapeka, 1845

References:

- Jump up ↑ P.14 The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period: Volume I: 1845–1864

- Jump up ↑ P.32, Belich, The New Zealand Wars

- Jump up ↑ P.45, Belich, The New Zealand Wars