Dr Bronwyn Hegarty has compiled this overview to start you off on your explorations and to get you thinking about this topic. She welcomes your contributions. Recommended citation: Hegarty, B. (2013). Reflective Practice: What is it really? Retrieved from http://wikieducator.org/GDTE/Reflective_Practice

What is Reflective Practice?

Understanding what is meant by reflective practice can be tricky. Some researchers give the impression that it is the same as reflection and use the terms interchangeably but this is not strictly correct. Reflection about practice is a part of it, but unless the process of reflection leads to learning and changes in your practice it is debatable whether reflective practice has occurred. Therefore, reflective practice in the true sense is much more than simply reflecting about practice. You will find the literature about reflection is vast, and contemporary views are different to some of the earlier theorists. This information is an attempt to guide you in finding your way through the maze. I begin with an overview of reflective practice, then introduce the concepts of professional learning and reflection which are components.

Definition of reflective practice

- Reflective practice is a process associated with professional learning, which includes effective reflection and the development of metacognition, and leads to decisions for action, learning, achievement of goals and changes to immediate and future practice (Hegarty, 2011a, p. 20).

So why this definition? Developing metacognition means that you are more likely to become a reflective practitioner because you have heightened self-awareness about your actions and the ability to monitor and critique your learning and performance to achieve your goals for practice (Hegarty, 2011a). These attributes are more likely to be developed if you engage in reflection and self-evaluation about practice. So what is meant by professional learning and effective reflection? You can read more about this further on.

Compare this definition of reflective practice with the one from The Teacher's Reflective Practice Handbook by Paula Zwozdiak-Myers (2012):

- Reflective practice is a disposition to enquiry incorporating the process through which student, early career and experienced teachers structure or restructure actions, beliefs, knowledge and theories that inform teaching for the purpose of professional development (p. 5). Both definitions have been developed for teachers and are linked to professional learning and development. Both authors also provide frameworks to help practitioners to develop their reflective practice abilities.

Dimensions of reflective practice

Click on the expand button  to the right of each dimension to view an explanation and details of related strategies:

to the right of each dimension to view an explanation and details of related strategies:

| [▼]Dimension 1: Study your teaching for personal improvement - Reflect regularly.

|

|

Case Study: Emilia

| In an earlier section we saw how Emilia has been keeping a reflective journal as part of her professional development as a new teacher.

Every Friday she reflects back on what she herself has done and learned during the week. She records in her journal not just what happened but also why and her own feelings and reactions to specific situations and the decisions she made. She also decides on some actions she needs to take to improve how she can work more effectively and sets goals for herself.

|

Reflection helps you to learn from your experiences and to develop as an expert practitioner. Decide on a definition of reflection and choose a preferred model or framework to guide you. You may now realise that reflection involves not only looking back (reflection-on-action) but can also be used in the midst of your practice (reflection-in-action) and for looking ahead (reflection-for-action).

Recording your reflections helps you to deepen your reflection and re-visit your experiences until you have gained insights into your practice. Ask yourself questions and where possible enter into dialogue with a critical friend who can prompt the direction of your reflections thus contributing to the reflective process.

Decide on the methods you will use to record your reflections about your practice - journal, blog, audio or video diary etc. |

| [▼]Dimension 2: Evaluate your teaching using Research - Action research and Inquiry.

|

|

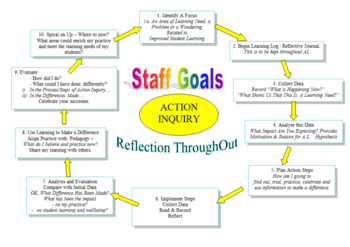

Action research (or action inquiry) generally begins with a problem you want to solve in your classroom with the intention of finding solutions. Ideally, students and other teachers become the participants. It is a cyclical process requiring an analysis of the problem and solutions. More than one cycle can occur. The diagram illustrates the process. The stages are:

- Identify an issue or problem,

- Develop a research question (hypothesis),

- Prepare a plan of action (teaching strategy or lesson plan),

- Implement the plan (teaching session or activities)- observation and data collection (your reflections, and responses of students and other teachers), and

- Evaluation of the plan (reflection, analysis, understanding, and decisions)

- Develop goals for a further cycle.

- These short videos by missmelissa73 give a very good introduction and reasons for using action research. They were created for primary teachers but the principles are the same for tertiary teachers.

Note: Formal research with students needs ethics approval prior to implementing the plan, and it is advisable to seek the advice of a colleague experienced in research, and obtain assistance to prepare your action research plan. Action inquiry can also be done informally to monitor the impact of your teaching strategies on your students. However, if you wish to disseminate your findings outside your immediate professional circle, you are advised to obtain ethics approval.

Case Study: Brett

|

Several of Brett's colleagues are involved in an action research project to improve learning and teaching by incorporating blended learning approaches.

Part of Brett's involvement in this project is to act as a mentor to his colleagues.

|

What problem would you like to solve in your classroom? |

| [▼]Dimension 3: Link theory with practice - Use the literature.

|

|

Case Study: Emilia

|

Because of Emilia's new role in educational design, she has had to develop her understanding of the field by by exploring some key educational theories.

Emilia says:

One of the most useful sources when I came into the role was Illeris' Contemporary Theories of Learning - one of the staff developers recommended it and it was really helpful in filling in a few gaps in my knowledge!

|

The body of theoretical knowledge about teaching is vast. However, the expert knowledge on which teacher education is based is not necessarily transferred to teaching contexts (Zwozdiak-Myers, 2012). Teachers generally have fabulous content knowledge about their discipline but little theoretical understanding of teaching. Barriers to the application of theoretical knowledge include teachers' preconceptions about teaching and their students, the timing of exposure to this knowledge, and information that is irrelevant for solving immediate or complex situations in the classroom.

Therefore, teachers need access to theoretical knowledge and research from the literature that makes sense in their context, and can provide practical solutions that they can implement. Reflection about practice under the guidance of an expert mentor can assist teachers (of any level of experience) to understand how to apply theoretical knowledge to their teaching contexts. In this way, they can be guided to design and use effective learning and teaching methods (pedagogies) based on theory and research that are relevant for their students, and will maximize access and engagement in the learning environment.

Case Study: Brett

|

Brett has an important role in his teaching team as a mentor and advisor. So he tries to keep up to date with the literature for the benefit of his whole team.

Brett says:

Because I'm involved in team members' action research projects, I've been reading Developing innovation in online learning: an action research framework by McPherson and Nunes.

It has helped provide a more structured approach to our blended learning projects.

|

Think of an example, where theoretical knowledge has helped your practice. |

| [▼]Dimension 4: Question your personal theories and beliefs - Critical analysis.

|

When engaging in the scholarship of teaching, personal theories and beliefs and assumptions need to be challenged. This requires critical analysis - interrogation and questioning of your assumptions, values and beliefs about teaching. You need to be sure that the views you hold have a sound basis, and are not just "idiosyncratic preferences" (a learned behaviour), or the outcome of taken-for-granted cultural practices ("cultural norms") and values of which you weren't aware; these aspects can become firmly entrenched leading to a narrow view of teaching (Zwozdiak-Myers, 2012, p. 85).

- For example, a teacher may hold traditional views that students can only learn if they attend lectures given by a teacher at the front of the class. This view that this form of 'didactic' teaching is the only way to teach, will most likely prevent this teacher from engaging enthusiastically in online teaching or contemplating more flexible approaches.

Case Study: Emilia

| In her new role within the education system, at first Emilia was used to thinking of teaching in terms of the way she was taught when she was student some years ago. But learning and teaching have changed since then!

Emilia's reflection and her interaction with colleagues have allowed her to reconsider her own assumptions about learning and teaching. She is able to see how these assumptions need to change if she is to function effectively in today's education system.

This has been a challenging process at times for her, but at the same time she has been able to develop her own self-efficacy as a teacher.

|

- Self-efficacy (belief in one's abilities)

- This is an important construct in reflective practice, since perceptions about self will directly impact on behaviour. This influences the opportunities practitioners might engage in, their motivation, their expectations of success and failure, the effort they make to succeed and use their skills, and their perceptions about potential barriers. All these aspects will impact on performance (Zwozdiak-Myers, 2012). The more confident teachers are, the more likely they are to take risks and extend their knowledge and skills through trying new things. For more information about self-efficacy theory, refer to this article: Self-Efficacy by Albert Bandura.

- Citation: Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In V. S. Ramachaudran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 71-81). New York: Academic Press. (Reprinted in H. Friedman [Ed.], Encyclopedia of mental health. San Diego: Academic Press, 1998).

Reflect on how comfortable you feel when asked to try a new teaching approach or use an unfamiliar technology. |

| [▼]Dimension 5: Consider alternative perspectives and possibilities - Learning conversations.

|

|

Case Study: Brett

| Brett's team has regular meetings where they share ideas, and he is actively involved as a mentor with several members of the team.

From time to time he observes his colleagues teaching. He follows this up with a meeting to give feedback and discuss how their teaching is going and things they might try to improve learner involvement and outcomes.

|

Conversations with yourself and your thoughts are useful during the reflective process. However, even more useful are discussions with others as these will expose you to a variety of viewpoints and ideas. This can help you to develop your knowledge in real-world contexts, that is, participate in a social learning environment (known as constructivist theory of learning). Using these learning conversations, the teacher can learn to think as an expert teacher might think and examine multiple perspectives about teaching.

Professional learning communities, mentors and peers are all great for facilitating learning conversations. Teaching observations can also be used in this way. Beneficial outcomes are more likely when the learning conversations are planned and structured so that the dialogue supports the teacher to reflect on practice, develop new knowledge and understanding and change future practice. Student feedback and evaluations can be used to trigger learning conversations. It is often the critical questions asked by a colleague that lead to revelations about our practice (Zwozdiak-Myers, 2012).

Engaging learners in conversations about learning can also be a powerful strategy for improving practice. There can be real benefits in making teaching and learning processes more explicit and discussing them with learners: see also Open teaching: sharing responsibility for the learning process.

How could you use learning conversations to develop your knowledge and practice of teaching? |

| [▼]Dimension 6: Try out new strategies and ideas - Innovation.

|

| Learning needs to be fun, authentic (real-world) as well as relevant. When it is, students are generally more motivated and more likely to engage in meaningful and deeper learning. The teacher usually tries to design learning experiences that help students to engage with specific content and concepts that they need to understand. Whether these are practical or theoretical experiences does not matter. What is important is to offer sufficient variety and challenge to keep students curious and interested. Modelling specific strategies in your teaching can demonstrate to students how they might do something.

Case Study: Brett

|

In an earlier section we saw how Brett encouraged teachers in his team to set up their own reflective blogs as a model for their learners.

This helped the students see the sort of thing that is required, as well as helping the teachers to become reflective bloggers and build their teaching capability.

|

Innovation can occur through the pedagogical approach that is used as well as in the technologies that support the learning. For example, a teacher might want to use project-based learning with groups. She decides to get each group to develop their projects using a blog and a wiki. Since this is a new approach for her and her students, it is important that she seeks advice from colleagues experienced in this approach, prior to starting and also during the process. She also needs to gauge how students are responding and to get feedback throughout so that she can respond appropriately. The critique of her peers and students and her reflections will help her to develop her expertise in this area. Nothing like innovation to stimulate reflective practice.

Learning conversations can also occur around discussions about theoretical knowledge and research evidence. Some practitioners meet regularly to discuss articles they have read or techniques they have used, others post on their blogs and invite discussion that way.

How could you use innovation to engage in professional learning conversations? |

| [▼]Dimension 7: Maximise the learning potential of students - Inclusive and flexible practices.

|

|

Case Study: Emilia

| One thing that surprised Emilia in her new role is how different the student body has become. When she was a university student, nearly all her peers were full-time students, school-leavers from within the New Zealand education system.

Now, the student body seems a lot more diverse - there are many more mature students now, many international students, and others from a wide range of backgrounds. And most are working and have busy lives outside of study.

Emilia realises that it will be important for her new course to meet these diverse needs, so she's thinking about how the course delivery could be made more flexible.

|

A design approach called Universal design is where "environments, objects, and systems that can be used by as many people as possible" (NC State University, 1997). This means that flexible choices must be provided with multiple alternatives for access and use. This is to ensure that people of any age, ability, gender, socio-economic status, ethnicity or culture etc. can be accommodated.

When teachers understand how to offer flexible learning approaches that meet the diverse needs and learning preferences of their students, exciting things can happen. Five dimensions of flexibility that can impact on students are related to: time; content of the course; entry requirements; instructional approaches and resources; delivery and logistics (Casey & Wilson, 2005).

Other approaches teachers can use to support learning are formative assessment and personalised learning. Feedback is an important aspect of assessment for learning and when done effectively can boost students' confidence and motivation.

How flexible is the learning environment that you provide and does it enable equitable access for all your students? |

| [▼]Dimension 8: Enhance the quality of your teaching - Effective practice.

|

|

Case Study: Brett

| Because of his senior position within his team, Brett sees a range of teaching styles and abilities.

Some of his colleagues are very good at communicating with students and seem enthusiastic and interested in their subject. Brett has noticed that this seems to have positive effect on student motivation and achievement.

|

Many factors have been found to have an impact on the effectiveness of teaching. For example, knowledge of the subject matter and passion, high expectations of themselves and the students, good skills for facilitating intellectually challenging and structured learning and for responding to the diverse needs of students. Also, teachers' self-efficacy and beliefs about teaching and their commitment and desire to help students achieve are regarded as influential. Additionally, personal factors such as having a good sense of humour and situations and events that occur outside the classroom also have an effect (Zwozdiak-Myers, 2012).

Professional growth of teachers is strongly linked to the quality of their teaching. If teachers systematically reflect on the outcomes of each lesson to examine why learning occurred or not, then they have an opportunity to build their knowledge and advance their expertise (Zwozdiak-Myers, 2012). Formative assessment and learning activities can be used to inform this dimension because they will signal the success of the teaching and learning strategies.

Also, if teachers can engage in reflective practice to gauge their performance against specific quality standards or criteria, researchers consider that they are more likely to improve their practice (Zwozdiak-Myers, 2012). However, in New Zealand no such standards exist and by gaining a tertiary teaching qualification, teachers are on the right path since specific criteria must be met in the graduate profile. Knowledge of pedagogical models and how to use information communication technologies (ICT) effectively for learning are essential ingredients for effective teaching in the 21st Century. Therefore, it is important that these areas are integrated in the professional development of teachers (Zwozdiak-Myers, 2012).

Reflect on the factors that may impact on the effectiveness of your teaching, and your goals for professional growth. |

| [▼]Dimension 9: Continue to improve your teaching - Professional learning.

|

Developing skills and knowledge for teaching is lifelong. As society changes and issues arise so does teaching, and trends in pedagogy and in technology are sweeping us off our feet. Educators need to be flexible and resilient enough to respond to the rapid changes that are occurring in society, particularly in information communication technologies (ICT). Case in point, is the influx of mobile devices to the market (e.g., smartphones, ipads, epads, and tablets), and the wealth of social networked media available via the Internet.

- Continual professional development

- Regarded as essential if teachers are to build their capacity for participating in dynamic educational environments. This requires individuals who are prepared to take risks, be innovative, and to work collaboratively with others to share their ideas and knowledge. Participation in professional learning communities or communities of practice has been shown to empower teachers in this way, helping them to advance their "tacit knowing" into "explicit knowledge" (Zwozdiak-Myers, 2012, p. 171). One-off workshops and events have limited usefulness since they are usually disconnected from the teaching context: see also Professional development for teaching with technology.

Three key competencies that have reflectivity at the core are considered necessary for citizens to participate in today's world. They were developed from an OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) project.

- Use tools interactively for communication - use dialogue, symbols and written language; digital information literacy and use technologies effectively;

- Interact in heterogeneous groups - respect the diversity of others, interact co-operatively and respond appropriately to conflict;

- Act autonomously - see the big picture, develop personal plans and participate in projects and be assertive. (Ryken & Salganik, 2005.)

Case Study: Emilia

|

Before Emilia took up her new role in education, she was part of a broad community of practice in the public health field. For example, she regularly presented papers at conferences, and was actively involved in an online community of public health practitioners.

Emilia is continuing her involvement in this community of practice as she sees it as still very useful and relevant. In addition, to support her new role she has sought out ways to be actively involved in the international community of practice of public health educators.

She also keeps a professional development portfolio to record her reflections about what she learns from her interactions.

|

- Professional learning communities

- Facilitate learning for colleagues with similar professional interests and within specific contexts. Learning is collective and shared, and often involves teams working towards a common vision. They can be conducted in the same physical space or online using a variety of tools (computer conferencing, discussion groups and social media).

- Communities of practice

- Specific professional learning communities that according to Etienne Wenger (2006), "Communities of practice are groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly". They are practitioners that develop a collective identity and commitment, and interact to build relationships and learn from each other. Reflective practice is a key component of both forms of professional learning.

- Professional development portfolio

- Creating and maintaining a portfolio, as well as engaging in communities, is regarded as essential for lifelong and continual professional learning. When used in conjunction with the support of a critical friend or mentor a portfolio can be a very powerful mechanism for lifelong and continual professional learning (Zwozdiak-Myers, 2012).

Develop a plan for engaging in continual professional learning and development. |

Definition of Professional Learning

- This is any learning which has relevance to professional practice and occurs when new knowledge and understanding, skills and insights are gained and may lead to the achievement of professional goals (Hegarty, 2011a, p. 20).

Professional development (both formal and informal) can assist with professional learning and from my perspective needs to be closely associated with activities that encourage effective reflection. Just attending training sessions or reading articles, for example, may trigger reflection about the activity, but may not lead to a change in practice unless the practitioner actively reflects on what is learned and applies this to practice.

Definitions of Reflection

- Reflection is deliberate and mindful thinking about one’s experiences and the self-evaluation of feelings, decisions, understandings and actions, which may lead to development of professional learning for professional practice. Reflection which demonstrates these attributes is regarded, in this research, as ‘effective reflection’ and is associated with reflective practice (Hegarty, 2011a, p. 20).

To think mindfully means that you really notice what happened during the experience or event. Self-evaluation means that you describe the experience at an emotional and self-questioning level and analyse what occurred and how it affected you. Acknowledging your feelings and reactions is an important part of this process. In this way, you can not only understand why you acted in the way that you did but can also attempt to explain the actions of others. Once you start examining others’ perspectives, whether it is those of colleagues or the information that you source in the literature, you can enter the domain of critical reflection…and that is another story.

Activities

|

Compare this definition of reflection by Jennifer Moon (2007):

- Reflection is a form of mental processing- like a form of thinking - that we may use to fulfill a purpose or to achieve some anticipated outcome, or we may simply ‘be reflective’ when an outcome may be unexpected. Reflection is applied to relatively complicated, ill-structured ideas for which there is not an obvious solution and is largely based on the further processing of knowledge and understanding that we already possess (p. 192).

- Use these definitions as a basis for developing a definition of reflection that suits your context. Here are some questions to help you on your way.

- What are your thoughts about the definitions of reflection, professional learning and reflective practice provided here?

- Do you agree with the definitions or not? Why?

- From your perspective is anything missing?

- Please share other definitions that you have found.

- Please post your thoughts and responses to this wiki page Discussion area so we can debate the ideas.

|

How can reflection be used for practice?

As you have probably realised by now, developing a contemporary definition of reflection is complex because the field is huge and researchers have varying opinions and perspectives. Some practitioners regard reflection as just thinking, whether it is in your head, on paper or with a colleague, friend or mentor. To some degree this is true. However, it is important to consider how the thinking is done (the cognitive process), why it has occurred and what it involves (the stimulus), as well as what it leads to at the end, e.g. learning and changes to practice (the outcomes). Hatton and Smith (1995) believe that as teachers develop their skills and gain experience, three specific types of reflection can develop:

- technical rationality (behaviours and skills);

- reflection-on-action (involving, descriptive reflection - description and justification; dialogic reflection - exploration; and critical reflection - multiple perspectives and factors); and

- reflection-in-action (thinking 'on your feet').

These researchers, who based their work on Schon (1983, 1987) found that the latter form of reflection was more likely when practitioners were experienced.

Activities

Begin learning about reflection and how to do it effectively:

- Access the interactive resource: The Reflective Learning Cycle (Hegarty & McConnell, 2011) to assist you to think about a past experience. (You may be prompted to login as a guest.)

- Discuss your case study with a colleague.

- Think about how this dialogue has helped you to understand further the experience that you documented in your case study, and record these thoughts using the framework.

|

Why is reflective writing necessary?

Let’s face it, thinking, thinking, and thinking with thoughts buzzing around in your head probably won’t get you anywhere that is helpful unless you have some structure and are able to reach discernible outcomes. From my perspective:

- Reflection is generally regarded as a specific and prolonged form of thinking, which if used effectively by professionals can help them to make sense of actions in practice and learn from them (Hegarty, 2011a, p. 3).

Therefore, it is important to take your thoughts and write about them; this is part of being a reflective practitioner. Menary (2007) considers that when you write you think. Therefore, by fashioning thoughts into a more permanent form by recording them you are more likely to extract meaning from your experiences. Therefore, when reflecting on your experiences through discussing them with a colleague it is a good idea to record the outcomes, preferably in writing. A number of models and frameworks are available further on to assist with this.

Refer to this resource - Reflective writing. Guidance notes for students. It was prepared by Pete Watton, Jane Collings and Jenny Moon (2001). It has examples of reflective writing, and pointers for deepening your reflections.

Reference as: Watton, P. Collings, J. & Moon, J. (2001). Reflective writing. Guidance notes for students. Retrieved from http://www.exeter.ac.uk/fch/work-experience/reflective-writing-guidance.pdf

What is critical reflection?

For reflection to extend to critical reflection, practitioners must engage in critical thinking and question the status quo. This means that they need to consider multiple perspectives and consider how their viewpoints and assumptions fit within the historical, socio-economic and political parameters of the profession and the world view. Metacognition and critical analysis of many factors play a part in this. Proponents of critical reflection believe that is necessary to practice at this level of reflection if practice is to be transformed (e.g., Fook & Gardner, 2007; Fook, White, & Gardner, 2006; Leach, Neutze & Zepke, 2003). Also, an aptitude for critical reflection relies on specific dispositions as well as experience, and novice practitioners are less likely to practice this type of reflection unless a more expert practitioner is available to guide them (Hatton & Smith, 1995). The role of critical reflection video gives a great overview of what it means to engage in critical reflection.

Models and Frameworks of Reflection

Many theorists have written about reflection and created models to represent their view of reflection. The models are represented diagrammatically and generally have guiding questions that can be used as a framework to structure reflection. The model is the representation. The framework provides the structure. Several models and frameworks are provided (in chronological order). See if you can notice the similarities and differences.

When developing your portfolio for assessment in the course, you may like to choose a model or framework which suits your learning style and context, and use it to guide your reflections. The context (e.g., health or education) for which each was developed is indicated.

- The Three-Step Reflective Framework was developed by Dr Bronwyn Hegarty (2011a). It is accompanied by a Three-Step template

that you can follow to structure your reflective writing. The prompting questions in the framework encourage you to really pay attention to your experiences, and move beyond basic description to analyse your actions, learning, and emotional reactions, thus examining your practice more critically and from several different perspectives. Context: Education.

that you can follow to structure your reflective writing. The prompting questions in the framework encourage you to really pay attention to your experiences, and move beyond basic description to analyse your actions, learning, and emotional reactions, thus examining your practice more critically and from several different perspectives. Context: Education.

- This review of Rodgers Reflective Cycle. It is based on this article: Rodgers, C. (2002). Voices Inside Schools. Seeing Student Learning: Teacher Change and the Role of Reflection. Harvard Educational Review, 72(2), 230-254. Context: Education.

- Driscoll's model (2000) has three stages: What, So what, What now? Context: Health.

- The Atkins and Murphy model of reflection was developed in 1994. It has model has five phases. The emphasis here is on uncomfortable or new experiences and challenges, and what was learned. Context: Nursing.

- Gibbs' Reflective Cycle (1988) represents a model with seven stages. The prompting questions begin with the context of what happened and ends with future actions. Context: Health.

Context: Education.

- Based on Boud, D., Keogh, R. & Walker, D. (1985) Reflection: Turning Experience Into Learning. London: Kogan Page.

References and Further Reading

- Remember this is a vast area, therefore this list is intended to guide your inquiry, and you wont need to look at everything, only material that is relevant to your learning goals. Please add additional material to this page to share with and assist others.

- You will need to Create a WikiEducator account. Collaborating and sharing material with others is an essential skill to develop if engaging in open learning and teaching practices.

- Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In V. S. Ramachaudran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 71-81). New York: Academic Press. (Reprinted in H. Friedman [Ed.], Encyclopedia of mental health. San Diego: Academic Press, 1998).

- Biggs, J. (1988). The role of the metacognition in enhancing learning. Australian Journal of Education, 32,127-138.

- Boud, D., Keogh, R., & Walker, D. (1985). Promoting reflection in learning: a model. In D. Boud, R. Keogh, & D. Walker (Eds.), Reflection: turning experience into learning (pp. 18-40). London: Kogan Page.

- Boud, D., & Walker, D. (1990). Making the most of experience. Studies in Continuing Education, 12(2), 61-80. doi:10.1080/0158037900120201

- Dewey, J. (1933). How we think. New York: D.C. Heath and Company.

- Fook, J., White, S., & Gardner, F. (2006). Critical reflection: a review of contemporary literature and understandings. In S. White, J. Fook, & F. Gardner (Eds.), Critical reflection in health and social care. Maidenhead, Berkshire: Open University Press.

- Hatton, N., & Smith, D. (1995). Reflection in teacher education: towards definition and implementation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 11(1), 33-49. doi:10.1016/0742-051X(94)00012-U

- Hegarty, B. (2011a). A Framework to guide professional learning and reflective practice. Doctor of Education thesis, Faculty of Education, University of Wollongong. Retrieved from http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3720

- Hegarty, B. (2011b). Is reflective writing an enigma? Can preparing evidence for an electronic

- portfolio develop skills for reflective practice? In G.Williams, P. Statham, N. Brown, B. Cleland (Eds.), Changing Demands, Changing Directions Proceedings ascilite Hobart 2011.(pp. 580 - 593).

- Retrieved from http://www.ascilite.org.au/conferences/hobart11/downloads/papers/Hegarty-full.pdf

- Illeris, K. (2008). Towards a contemporary and comprehensive theory of learning. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 22(4), 396 - 406.

- Menary, R. (2007). Writing as thinking. Language Sciences, 29(5), 621–632. doi:10.1016/j.langsci.2007.01.005

- Moon, J. (2007). Getting the measure of reflection: considering matters of definition and depth. Journal of Radiotherapy in Practice 6(4), 191-200. doi: 10.1017/S1460396907006188

- Ryken, K., & Salganik, L. (eds) (2005). The Definition and Selection of Key Competencies: Executive Summary. DeSeCo project. Neuchâtel: Federal Statistical Office. Retrieved from http://www.deseco.admin.ch/bfs/deseco/en/index/02.html/

- Schön, D. (Ed.). (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. USA: Basic Books Inc.

- Schön, D. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Zwozdiak-Myers, P. (2012). The Teacher's Reflective Practice Handbook. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Zwozdiak-Myers, P. (2012). The teacher's reflective practice handbook. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

![]() to the right of each dimension to view an explanation and details of related strategies:

to the right of each dimension to view an explanation and details of related strategies:

that you can follow to structure your reflective writing. The prompting questions in the framework encourage you to really pay attention to your experiences, and move beyond basic description to analyse your actions, learning, and emotional reactions, thus examining your practice more critically and from several different perspectives. Context: Education.

that you can follow to structure your reflective writing. The prompting questions in the framework encourage you to really pay attention to your experiences, and move beyond basic description to analyse your actions, learning, and emotional reactions, thus examining your practice more critically and from several different perspectives. Context: Education.