BaCCC/Module 5/Lesson 1/Part 1

Contents

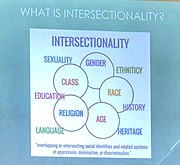

Module 5, lesson 1: What is What Is Intersectionality?

Introduction

A society is composed of human and non-human species, but human populations are different from other species because we have cultures. Even though we may belong to the same culture, there are differences between us based on our age, sex and gender, occupation, ethnicity, access to resources, differing abilities and other traits. Think of your own community . . . how many “categories” of people do you see? And how many of those categories overlap in the same person? That is intersectionality.

In this lesson, you will become familiar with the concept of intersectionality. It introduces the value of both counting every individual’s experience in facing the challenges of climate change and learning from one another. This lesson will help you develop your understanding of intersectionality by identifying different characteristics of people in society, including age, gender, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity and language, class and socio-economic status, and ability or disability, among other things.

Terminology

The following terms are important in understanding the science behind climate change. If you want to remember them, write their meanings in your learning journal as you encounter them in the course content.

- climate justice

- climate resilience

- intersectionality

What is intersectionality?

Intersectionality is a concept that was first introduced in 1989 by Kimberlé Crenshaw, an American legal scholar and critical race theorist, to help people see how intersecting and overlapping social identities of gender and race bring about discrimination and marginalisation, which is the act of placing a person in a position of lesser importance, influence or power; in other words, pushing them to the margins of society. See Professor Crenshaw’s story below.

It originally referred to the way in which race and gender intersect and interact to shape a person’s experiences of oppression and privilege. (“Privilege” refers to often unacknowledged social advantages, benefits or degrees of prestige and respect that individuals have because they belong to particular social identity groups.)

Over the years, intersectionality began to consider other forms of marginalisation brought about by systemic oppression (historical and organised patterns of mistreatment) based on different social identities such as ethnicity, caste, age, disability, mental health, sexual orientation, class, religion, size, membership in specific groups, indigeneity, etc. (Indigeneity is the quality of a person’s or a group’s identity that links them to specific places or territory with knowledge of and respect for original ways of being and living on, with or in the land.)

Many of our social justice problems are often overlapping, creating multiple levels of social injustice. . . .

| “ | Intersectionality originated as a way to discuss how systems of oppression overlap and create distinct experiences for people with multiple identity categories. | ” |

| —Kimberlé Crenshaw | ||

- "Intersectionality is quite a new concept. We must make people aware of this idea. I believe it will help address the needs of the vulnerable sections of society. Our target is to shift from vulnerability to prosperity through resilience, and in order to achieve this goal, we have to take the concept of intersectionality very seriously." — Dilara Zahid, Acting Director of the Institute of Disaster Management and Vulnerability Studies, Dhaka University, Bangladesh

- "Intersectionality is not just about an individual’s complex personal identity. It is about the operations of the power structures in a society that intersect and interact to create a system of injustice as well as privilege. We need to understand intersectionality and put it into action." — Maureen Fordham, Professor of Gender and Disaster Resilience, Director of the Institute for Risk and Disaster Reduction, Centre for Gender and Disaster, University College London (cited in The Daily Star, 2022)

- "Intersectionality is an analytical framework for understanding how a person’s various social and political identities combine to create different modes of discrimination and privilege. Intersectionality identifies multiple factors of advantage and disadvantage." — Wikipedia

- "Intersectionality is a framework for understanding the complex way that the many aspects of people’s identities overlap, including their race, gender, sexual orientation, class, and more. Intersectionality holds that a person’s various identities do not live in separate vacuums; rather, people exist at the intersections of their identities." — Eliza Sullivan, What Is Intersectionality?

What Is Intersectionality and Why Is It Important?[1]

- "Intersectionality is the theory that the overlap of various social identities, such as race, gender, sexuality, and class, contributes to the specific type of systemic oppression and discrimination experienced by an individual." — Dictionary.com

- "Intersectionality offers a way to understand and respond to the ways that different factors, such as gender, age, disability, and ethnicity, intersect to shape individual identities, thereby enhancing awareness of people’s needs, interests, capacities, and experiences." — Mahbuba Nasreen, professor and co-founder of the Institute of Disaster Management and Vulnerability Studies, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh

- "Over the years, it has been observed that concepts like gender or class alone cannot explain the entire discourse [discussion] around vulnerability to disasters. Looking through a sole lens obscures how a number of intersecting factors further disadvantage certain people. . . . Therefore, it is necessary to use an intersectional lens to address different types of vulnerability." — Ramona Miranda, Head of the APP-DRR Stakeholder Group, United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction

|

Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw likes to recount the story that led to the “intersection” analogy. She had read the judge’s decision in a case about an African-American woman who sought a job in a car manufacturing plant but was not hired. This woman sued for race and gender discrimination, but the judge threw her case out of court, saying that because black men worked in the company’s factory and white women worked in the company’s office, the company did not discriminate against women or black people. He could not see the complainant’s dilemma, that the company would not hire her because she was a black woman. “It felt to me like [it was] injustice squared,” Professor Crenshaw says. Why could the judge not see that black women were not being hired to work at the plant – and that was discrimination? She realised that this problem did not have a name, and it is hard to even see a problem, let alone solve it, when it does not have a name. Many years later, Professor Crenshaw realised that this was a framing problem. “The frame [short for ‘frame of reference,’ which is the complex set of assumptions, attitudes and biases through which we each filter our perceptions to create meaning out of the world] that the court was using to see gender discrimination or to see race discrimination was partial, and it was distorting.” The alternative narrative that she came up with was the “simple analogy” (her words) of an intersection of two roads. “The roads to the intersection would be the way that the workforce was structured by race and by gender. And then the traffic in those roads would be the hiring policies and the other practices that ran through those roads. [If a woman is both black and female], she is positioned precisely where those roads overlapped, experiencing the simultaneous impact of the company’s gender and race traffic. “The law is like that ambulance that shows up and is ready to treat [the woman] only if it can be shown that she was harmed on the race road or on the gender road, but not where those roads intersected. “If you’re standing in the path of multiple forms of exclusion, you’re likely to get hit by both. “So, what do you call being impacted by multiple forces and then abandoned to fend for yourself? Intersectionality seemed to do it for me.” |

(You can adjust the playback speed and/or turn on subtitles/captions.)

H5P Object Parameters

The H5P parameters below will be replaced by the actual H5P object when it's rendered on the WordPress site to which it's been snapshotted.

In the context of climate change adaptation, intersectionality highlights the importance of recognising and addressing the differential impacts of climate change on various communities. It recognises that different social identities intersect in complex ways to shape people’s lived experiences of climate change and their ability to respond with resilience to its impacts.

For example, low-income communities and communities of colour are often disproportionately impacted by climate change due to their location in polluted neighbourhoods (where polluting factories have been built nearby), flood-prone areas (these are sometimes the least expensive places to rent, build or live) or extremely hot urban heat islands (lots of asphalt pavement and very few trees and green spaces; the urban heat island effect occurs when a city experiences much warmer temperatures than nearby rural areas, caused by the lack of greenery, all the energy from all the cars, buses and trains, and how well the surfaces in cities absorb and hold heat.)

In countries that are still developing economically, intersectionality is particularly relevant to climate change adaptation. These nations are often more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change due to their limited resources and infrastructure at the government level, as well as their dependence on natural resources for their economic livelihoods.

Within these nations, marginalised communities, such as women and children, Indigenous peoples, people with disabilities and rural populations, may also be more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change due to existing social and economic inequalities. For instance, women in many developing nations are responsible for water and food security but may have limited access to resources and decision-making power, making them more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, such as droughts or flooding.

Using intersectional approaches in climate change adaptation in developing nations (and for the most vulnerable in developed nations) means recognising the intersecting social identities that shape people’s experiences of climate change, as well as working to develop solutions that are inclusive and equitable.

This involves engaging with marginalised communities to better understand their needs and experiences and working to develop adaptation strategies that are tailored to their specific circumstances.

It is important to note that intersectionality was conceived in an American legal context, and not every aspect of it crosses all cultures or settings. For example, when it comes to size, in some cultures heavy people are marginalised, but in other cultures, heaviness can represent wealth and health. When it comes to age, in some cultures the elderly are highly respected and revered, whereas in other cultures, they are ignored or discriminated against through ageism. In other words, who is oppressed and who is privileged may depend on your culture.

Also note, however, that women have full equal rights (from a legal perspective) in only 14 countries in a world of nearly 200 countries: Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Latvia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and Sweden. See:

Countries with Most Equal Rights for Women[2]

The top ten countries for women’s rights and opportunities, in general, are Iceland, Finland, Norway, New Zealand, Sweden, Namibia, Rwanda, Lithuania, Ireland and Switzerland. According to the World Economic Forum (2021), at the current rate, it will take approximately 100 more years “for women to be on an equal footing to men around the world.”

What this means is that everyone involved in climate change mitigation, adaptation and resilience building must deliberately seek women’s participation and make sure that their voices – and their lived experiences and ideas – are heard.

You can adjust the playback speed and/or turn on subtitles/captions.)

H5P Object Parameters

The H5P parameters below will be replaced by the actual H5P object when it's rendered on the WordPress site to which it's been snapshotted.

References

- ↑ Sullivan, E. n.d. What Is Intersectionality and Why Is It Important?

- ↑ Statista, n.d. Countries with Most Equal Rights for Women

- ↑ This Is How You Can, n.d. Wheel of Power and Privilege