Winslow Homer,

A Good Shot, Adirondacks, 1892. Watercolor on paper, 38.2 × 54.5 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

show the relative size of one form in relation to another. Scalar relationships are often used to create illusions of depth on a two-dimensional surface, the larger form being in front of the smaller one. The scale of an object can provide a focal point or emphasis in an image. In Winslow Homer’s watercolor

A Good Shot, Adirondacks, the deer is centered in the foreground and highlighted to assure its place of importance in the composition. In comparison, there is a small puff of white smoke from a rifle in the left center background, the only indicator of the hunter’s position. Scale and proportion are incremental in nature.

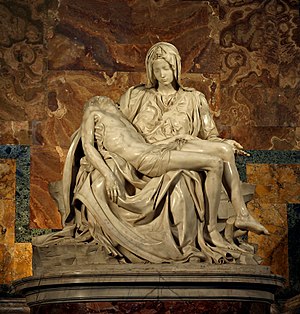

Michelangelo,

Pieta, 1499. Marble, St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome

Works of art don’t always rely on big differences in scale to make a strong visual impact. A good example of this is Michelangelo’s sculptural masterpiece

Pieta from 1499. Here Mary cradles her dead son, the two figures forming a stable triangular composition. Michelangelo sculpts Mary to a slightly larger scale than the dead Christ to give the central figure more significance, both visually and psychologically.

When scale and proportion are greatly increased the results can be impressive, giving a work commanding space or fantastic implications. Rene Magritte’s painting Personal Values constructs a room with objects whose proportions are so out of whack that it becomes an ironic play on how we view everyday items in our lives. American sculptor Claes Oldenburg and his wife Coosje van Bruggen create works of common objects at enormous scales. Their Stake Hitch reaches a total height of over 53 feet and links two floors of the Dallas Museum of Art. As big as it is, the work retains a comic and playful character, given in part to its gigantic size.