Art Appreciation and Techniques/Module 7

The following is an initial page plan for this unit. The beginning text, before the colon, is the proposed page name. We will use the mytitle template to name the pages with a fuller title, as needed; the navigator will include just the one/two words for each:

- Overview: beginning through learning outcomes

- Introduction: Introduction

- Identity:

- Self-portraits:

- The natural world:

- Social and collaborative art:

- Politics, conflict and war:

- Memorials:

- Peace:

- Summary: conclusion section

Contents

Art and Our World: Nature, the Body, Identity, Sexuality, Politics, and Power

In this module, we look at how artists express and interpret our world. Here are the topics and themes we’ll cover:

- Identity

- Self-Portraits

- The Natural World

- Social and Collaborative Art

- Politics, Conflict and War

- Memorials

- Peace

Learning Outcomes

- Define visual information as a source of knowledge.

- Describe how what we know is reflected in works of art.

- Explain and identify how artists use the natural world as a vessel for human experience.

- Explain how the use of animals as subject matter in art offer clues to cultural differences.

- Explore how art is a medium for self-identity.

- Explain the limits of representation of the body.

- Explore the idea of primordial couples and ties to human procreation.

- Describe sexuality in art seen through different cultural perspectives.

- Identify art as propaganda.

- Identify art as a vehicle of the state.

- Describe art and repression in societies.

- Explain art as a form of protest.

Introduction

If nothing else, visual art provides an avenue for self-expression. As a primary source, artists express attitudes, feelings and sentiments about the world around us through personal experiences, social interaction and our relationship with the natural world. In short, art gives us a perception of or a reaction to our place in the world. This idea is illustrated in the French artist Paul Gauguin’s painting titled: Where Do We Come From? What are We? Where Are We Going? The work brings us on a symbolic journey that includes imagery of infancy, adulthood, nature and spirituality.

In Module 1, we referred to description as one of many roles art affords us, but this description is often imbued with the artist’s subjective interpretation. In this module we will examine how art operates as a vehicle for human expression, a kind of collective visual metaphor that helps define who we are.

Identity

The art historical record is filled with images of ourselves. Generally, the further back we go the more anonymous these visages are. For example, the earliest works of art – crudely chiseled stone sculptures – record the human figure in exaggerated forms. The Venus of Berekhat Ram is dated to around 230,000 years ago. It, and other small stone figures from the same period, indicate that artistic expression was part of a pre-homo sapiens culture. There is now evidence of an ‘art instinct’: a natural inclination for humans to be creative and perceive our surroundings with an aesthetic sense*.

The Venus of Willendorf (pictured below), dated to about 20,000 years ago, is an archetype of early human expression. The sculpture is remarkable for what is included and what is missing. The female figure’s arms are draped over enormous breasts, and the enlarged genitalia, short legs and exaggerated midriff reinforce the idea of a fertility figure. The tightly patterned headpiece indicates either braided hair or a knit cap. Missing from this extraordinary figure is any hint of facial identity: she may represent a solitary female or the collective idea of womanhood.

These faceless and enigmatic figures persist in art for thousands of years. We see them again in figurines from the Aegean Cycladic culture dated to about 3000 BCE (image below). Their form is standardized, with smooth surface texture, triangular heads and crossed arms. You can even see a resemblance to these figures in certain modern sculptures, particularly by Romanian artist Constantin Brancusi from the early 20th century. His Sleeping Muse from 1909 is an example.

Ancient Jomon cultures of Japan produced extremely stylized earthenware figures, often female and, similar to the Venus figures of Western Europe, with enlarged breasts and hips but disproportionately short arms and legs. Thought to be ritual figures, the earliest examples are faceless and without adornment. Later ones show generic features with curious insect eyes and more elaborate decoration.

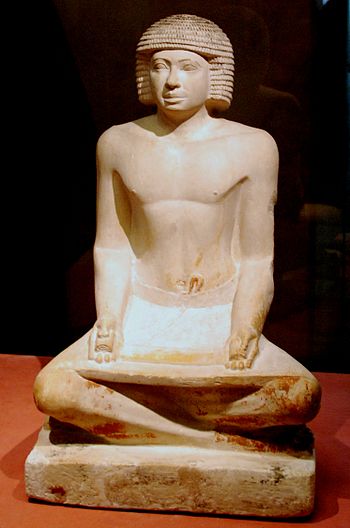

We start to see human figures with individual characteristics during the Old Kingdom dynasties of Egypt about 2500 BCE. Reserved for royalty and other high-ranking figures, these portrait sculptures, many times containing a man and women together, include an emotional connection as they stand or stride forward with their arms around each other. In another example below an Egyptian scribe sits cross-legged with his palette and papyrus scroll and a hairstyle comparatively similar to that of the Venus of Willendorf. Here we get a much stronger sense of identity and form, with detailed description of the scribe’s facial features, subtle but important rendering of musculature and even individual fingers and toes, all sculpted in correct proportion and scale.

Greek vase painting uses figurative and decorative motifs to illustrate mythic narratives or simply depict scenes from everyday life. Many of the vases show athletic games, social gatherings or musical entertainment.

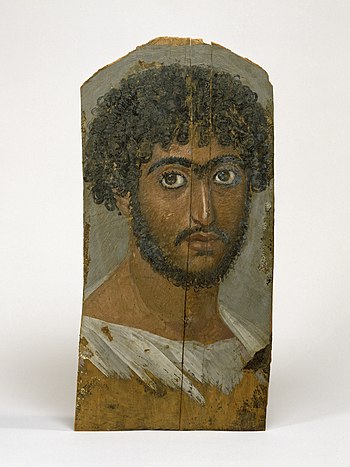

The Romans used painted portraits to commemorate the dead. Commonly known as Fayum mummy portraits, they were created with encaustic or tempera paints on wooden panels and placed over the face of the mummified body. The portraits all show the same stylistic characteristics including large eyes, individual details and the use of only one or two colors. The portrait below shows a young man with curly hair and light beard. There is also a melancholy psychological element as the figure stares back at us.

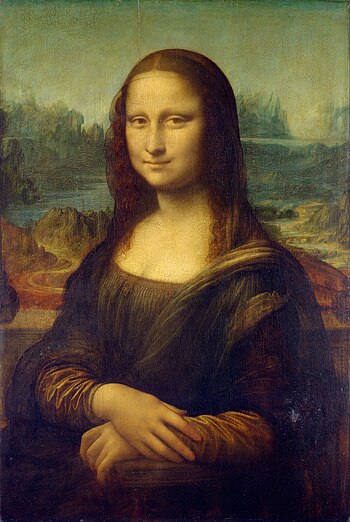

Perhaps the most famous portrait in the Western world is Leonardo Da Vinci’s LaGioconda, more commonly known as the Mona Lisa. The painting embodies many of the attributes we look for in a portrait: realistic form, detailed rendering of the sitter’s features and an intangible projection of theircharacter. These qualities emanate from the genius and skill of the artist. Her gentle gaze and slight smile has endeared the Mona Lisa to viewers around the world for over 500 years.

Portraiture and the figure continue to be important motifs in modern and contemporary art. Pop artist, Andy Warhol, used photographs of politicians and Hollywood celebrities to create series of images that supplant traditional painted portraits and reinforce our idea of brand identity. His diptych of Marilyn Monroe from 1963 signifies her place on popular culture’s altar as an icon of beauty and sexuality while alluding to her tragic suicide in 1962. The print’s bright colors and rapid-fire images on the left hold our attention while on the right we see her fading away into obscurity in black and white. With this staccato image format Warhol presents us with conflicting alternatives: the ubiquitous nature of celebrity and the fleeting nature of life.

Bruce Nauman’s neon sculpture Human/Need/Desire uses words that uncover “fundamental elements of human experience*”. The pulsating neon sculpture has a trance-like effect as the viewer watches the words change in front of them. The work provides a collective meaning because we can all identify with its message.

The painter Alice Neel’s portraits are exceptional as they capture a sitter’s likeness and character but with an expressionist edge. She preferred informal poses, used harsh colors and an unerring sense of design in portraits of family, friends, fellow artists and political personalities.

Finally, in an artistic gesture that redefines what portraiture and self identity can be, Spanish-born artist Inigo Manglano-Ovalle does away with the figure altogether. His three-panel chromogenic print Glen, Dario and Tyrone presents us with the DNA signature of each individual. This work blurs the line between art, science and technology. Now a portrait is manifest as blobs of color and its integrity is established by the fact that each series of blobs is genuinely different than any other. This creative idea has even migrated to the marketplace: You can order your own (or someone else’s) DNA portrait for the home or office.

Self-Portraits

Self-portraits direct an artist’s gaze inward. Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs from the 1970’s and 80’s include fashion, portraiture, floral arrangements and documentary subject matter. His self-portraits combine elegance in form with an autobiographical journey in content as he travels as a young gifted artist through the darker side of the New York gay S and M scene and ultimately to his death from AIDS at age thirty three.

In contrast to Mapplethorpe’s photos, Chuck Close has been producing portraits of family, friends and himself exclusively since the 1960’s. His unconventional style has changed little over the years. Starting from a photograph, he painstakingly translates the image into paintings, prints and drawings using a grid to isolate very small areas of a surface at a time. This slow buildup of form is both mechanical and magical. The resulting portraits stun with their visual presence –the paintings are often eight feet high – and incessant in their flatness to the picture plane. After suffering a spinal chord injury in 1988 that left him severely paralyzed, Close’s signature super-realism has evolved into mosaic-like images that seem at once both realistic and abstract.

And Robert Arneson’s ceramic self-portrait California Artist from 1982 is satirical in nature. He pokes fun at the classical ideal of sculpture grounded in the Greek and Roman traditions. Instead of appearing as an idealized mythic god, Arneson presents himself as a balding, middle-aged hippie, set on a chipped pedestal that includes a marijuana plant growing up the front and empty beer bottles and cigarette butts crushed out on its base.

Nature

The natural world has always given artists subject matter to experience and interpret. In it we find some of our greatest fears, so we try to organize it. It gives us spectacular joy, so we mimic it. Its grandeur motivates some of our highest aspirations, so we spin it in myth and symbolism. Our relationship with nature presents ironies too: it’s referred to as a maternal force, yet advanced societies are the most removed from it. All of these characteristics of nature become the stuff of artistic expression.

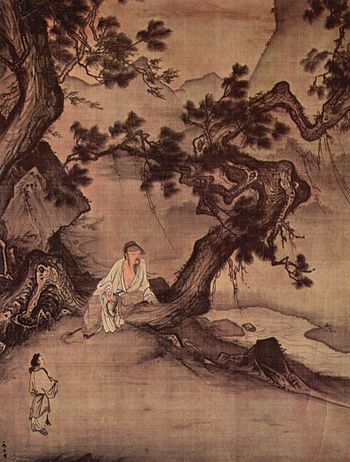

Chinese culture includes a reverence for nature that’s reflected in its traditional painting styles. Landscape is used as metaphor to illustrate physical, philosophical and spiritual themes. We looked at Ma Lin’s wall scroll in Module 5 in terms of the artist’s painting technique. Let’s reexamine it now (view the image below) to see how Lin creates subject matter that gives prominence to both nature and the figure. First of all, he animates the landscape to emphasize its scale and undulating features, contrasting large boulders and strong, twisted pines in the middle ground with a more subtly painted background of mountains and water. A figure (a wanderer, priest or poet) rests at the base of a pine, more in contemplation and unity with his surroundings than in opposition to them. Notice how this figure is painted with colored pigment that brings an emphasis to his place in the composition. A second, even smaller figure inhabits the foreground on the left, enhancing the landscape’s sense of scale.

In Loquats and Mountain Bird (also below), the artist’s keen observational skills give specific information, but the work transcends mere physical description of the subject matter. Through formal composition and the artist’s deft touch we see a slice of nature – in a very shallow space, that is unified and completely believable. A similar but perhaps less poetic effect can be seen in the works of John James Audubon (see his print Carolina Parakeet below). Audubon spent years documenting the birds and animals in America during the first half of the nineteenth century. The shallow space and strong use of placement, color and pattern give a more dramatic edge to his images.

In another more contemporary example, the glasswork of Ginny Ruffner provides a whimsical approach to her experiences with the natural world, providing delicate visual comments like the simple pleasure of looking out a window or marveling at the cyclical rhythms of water.

The natural world and our own experiences within it are incorporated into more utilitarian forms of art too. Architecture, often seen as an inorganic structural component, can mimic the landscape surrounding it. The 15th century Inca site of Machu Picchu in Peru contains dwellings with pyramidal stonewalls rising like the nearby mountain the site is named for. In addition to the buildings being extremely stable, their design directly reflects the cultural importance given the entire area. Machu Picchu was the center of Inca civilization. The development included terraced farms, homes, industrial buildings and religious temples.

Social and Collaborative Art

Art contributes to many social functions too. Parades feature colorful banners, extravagant floats and plastic inflatable characters from pop culture. Many ceremonies and rituals rely on works of art to act as vessels for the spirit world. Totem poles tell elaborate stories, using real and mythic animals to illustrate them. The Haida totem poles pictured below have a hierarchal structure to them so that the most important character in the story is at the top of the pole.

In another example, one of the functions for the calabashes mentioned above is to distribute beer at both social festivals and sacred rituals.

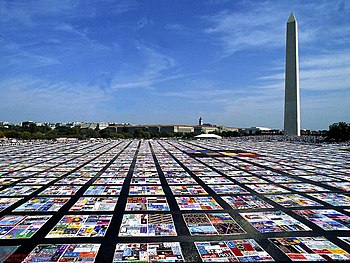

The NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt pictured below combines thousands of individually created quilts, each bearing the name of a victim of AIDS, into a collective image of loss and remembrance for family members and friends. Exhibiting the quilt around the United States has brought awareness about the disease to the general public.

Artists sometimes work in collaboration with others that have special technical training or knowledge in a particular medium to create something they couldn’t do on their own. In an example, Canadian artist Rolf Harder teamed with Design Collaborative Montreal to create the Peace Bridge Stamp.

The Chicago Public Art Group is a collaborative organization creating murals, mosaics and other art works for public spaces. Each project carries a theme significant to its specific location: from a colorful mural seen by commuters at a rapid transit stop to “Hopes and Dreams”, a large mosaic panel in downtown Chicago welcoming the new millennium. Each project is unique and involves the work of many artists, planners and volunteers.

As a final example, the Burning Man celebration at Black Rock City in Nevada draws thousands of people - artists and non-artists, in a week-long festival of art installations, performances and elaborate costumes that surround the construction and ultimate immolation of a massive effigy known as the Burning Man. The festival’s creativity and expression serves a communal social function. In the photo below you can see the concentric layout of Black Rock City – constructed and taken down each year – with the Burning Man sculpture isolated in the middle.

Politics, Conflict and War

The experiences of politics, conflict and war have been represented in works of art for thousands of years. They become documents, signifiers and symbols for power, remembrance, culture and national pride.

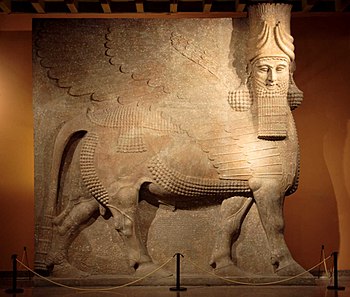

An ancient symbol of this power is the sculpture of Lammasu (below), a protective spirit carved into a massive bas-relief into the main gate of the Assyrian court nearly two thousand years ago. The figure has the head of a man, the body of a bull and the wings of an eagle.

In another subtler example but with no less visual effect, a ceramic Standing Male Warrior from the Mayan culture of Central America (in the photo below) looks out at the viewer in a stance of informal attention. The figure is only eleven inches high but gives us a trove of information about how Mayan soldiers dressed for battle. A thick vest with detailed patterning covers his torso. A necklace with heavy cupped objects (possibly sea or turtle shells) protects his upper body. The thick belt and loincloth at his waist and the strong bracelets on each wrist add to his protection. The round earrings are typical Mayan accessories. The fingers of his right hand are slightly curled as if he held a club or spear at one time.

For all the restrained beauty in the sculpture, the warrior’s shield and helmet dominate the composition. The shield, held at ease just above the figure’s foot, is embellished with a centralized mask and radiating scallops around the outer edge. The whole shield looks battered and bent from use. The helmet is in the form of an eagle or hawk’s head, surrounded by a heavy necklace of rectangular bars. Vestiges of paint still cling to parts of the sculpture, and it’s easy to imagine how colorful it would have first appeared.

Compare the Standing Male Warrior to the Terra Cotta Army from China (also pictured below). Discovered in 1974 and dating to the second century BCE, the Chinese figures, all life size, stand in neat rows to guard the nearby tomb of Emperor Qin. In this instance the idea of power and preservation of order is carried into the afterlife. Each soldier’s face is modeled as an individual and their armored robes show lots of detail and patterning. Similar to the Mayan figure, their right hands are curled to hold a club, spear or other kind of weapon.

Nations identify themselves with specific images. A flag is an example that best represents a particular nation. There is symbolic meaning in a flag’s colors, the depicted objects and any text that may be included in them. For example, each white star on the American flag represents one of the fifty states that comprise the nation. In comparison, the flag of Mongolia uses a sky blue central bar, the country’s national color, and incorporates Buddhist religious symbols in yellow on the left.

“Uncle Sam” (below) is a figurative representation that symbolizes the United States (“Uncle Sam” stands for “U.S”). He is dressed in America’s symbolic colors red, white and blue. This stern-faced visage was used in state advertising to recruit young men to the Army during World War I and is now an icon of American political history.

Until now we have looked at examples that infer war and conflict. Let’s take a look at one that shows the battle as it happens.

The Japanese war epic The Tale of Heiji contains a series of texts and scroll paintings describing the Heiji Rebellion from the tenth century. The scroll section below shows rebels burning the Imperial Sanjo Palace in Kyoto. While flames and smoke rise from the palace the chaos of battle goes on around it. Here war itself becomes the subject matter of the artwork, giving a historical account of the action but also a graphic aesthetic description of the event.

One of the most famous testaments to the horrors of war is Pablo Picasso’s Guernica from 1937. We saw this work in previous modules in the context of how the artist prepared and organized the final painting through sketches, studies and changes in the actual work. Picasso painted Guernica in response to the bombing of the Spanish Basque town by the German air force at the request of Spain’s General Franco during the Spanish Civil War. Picasso shows us a nightmarish scene of death and destruction within an orchestrated chaos of black, white and gray. The bull on the left is interpreted as Franco himself, watching passively over the carnage in front of him. The gored horse near the middle represents the Spanish people – wounded and flailing as they try to resist. A figure thrusts a candle through the open window at the upper right, a reference to the rest of the world as they watch the atrocities taking place. The only direct evidence of battle lies in the dead soldier on the floor, still clutching his broken sword (refer back to the right hands of the Mayan Standing Male Warrior and the figures in the Terra Cotta Army to see visual comparisons to Picasso’s soldier).

During the 1970’s and 1980’s artist Leon Golub created a series of paintings documenting the abuses that can arise in unstable political climates. Golub’s Mercenaries shows soldiers for hire as they call out and taunt each other in an atmosphere of disorder. They lack the discipline of a trained army, and Golub capitalizes on this idea by arranging the figures in a disjointed, asymmetrical composition. His use of a large-scale format (the painting is nearly 8 feet high) and the compliments red and green increases the menace and power of the figures. In the artist’s words:

“The mercenary is not a common subject of art, but is a near-universal means of establishing or maintaining control under volatile or up-for-grabs political circumstances”*.

- *Leon Golub The Mercenaries, Interview with Matthew Baigell (1981)

Memorials

The aftermath of war gives rise to memorials as vessels of remembrance for those who died. They are literally touchstones for families, friends, communities and entire nations to grieve. As works of art they provide a public space of honor and resolve to never forget the lives and sacrifices made by those who go to war.

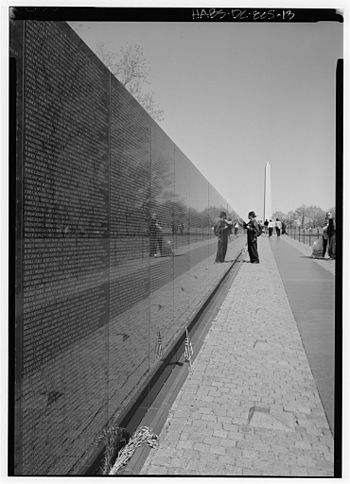

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. (below) is an example. Designed by the architect and sculptor Maya Lin, Its abstract formal design, wedge shape and placement created a new approach to traditional memorial design ideas. The work is set into an earthen embankment facing out to the viewer. It’s made with a dark gabbro stone that when polished produces a highly reflective surface. The names of 58,191 soldiers killed or missing during the conflict are cut into the stone face. Visitors walk a gently descending pathway towards the center of the memorial, the wall of names becoming larger as you go, to a height of ten feet at the middle. As they stare at the rows of names on the wall visitors see their own image reflected back. The path rises as you walk toward the other end (see the second image below).

Peace

Like so many other things we experience in our world that translate into art, those that engender ideas of peace and tranquility take many different forms. Some of these are iconic, others transitory and changing.

One such icon is a 19th century painting by Edward Hicks. In the Peaceable Kingdom, Hicks describes the world with a visually literal translation of bible verse: The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid, and the calf and the young lion and fatling together; and a child shall lead them.”

Hicks' painting (of which there are many versions), includes the scene of English colonist William Penn’s signing of a treaty with the Leni Lanape tribe of Native Americans.

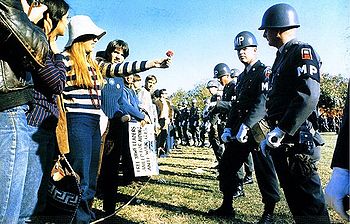

In the photograph below, a young woman participating in a peaceful demonstration in the 1960’s holds a flower out to a military police officer. This small gesture is significant because it breaks the tension of the standoff between them and is akin to a universal symbol of peace: a dove carrying an olive branch.

Other artistic expressions of peace include large public monuments. One example is the Peace Arch in Blaine, Washington (see the image below). Built in 1921, the stone arch straddles the international boundary between the two countries and commemorates the ongoing peaceful coexistence between Canada and the United States.

Related to this arch are many others collectively called Arches of Triumph. These arches stretch through art history starting from Roman times. They signify peace through the idea of military victory and national pride. The Arc de Triomphe in Paris is perhaps the most famous (see the image below). Built in the fist half of the nineteenth century, the arch stands as a victory monument to all French soldiers who fought in the Napoleonic Wars, and since then has become an icon of French victory over aggression and war. At 162 feet high, its massive bulk and beautiful proportions are a testament to permanence.

A more contemporary example of peace, and one that is etched into popular culture, is the graphic Peace Symbol (below) designed by Gerald Holtom in 1958 for use in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. It is a universal signifier for peace and can be found on flags, buttons, banners and clothing. The symbol is incorporated on the Lennon Wall, a public space in the city of Prague in the Czech Republic dedicated to the memory of John Lennon, the late member of the Beatles rock band and an activist for peace. In the 1980’s Czech youths tagged graffiti on the wall as an outlet for their frustration against the Communist regime in power at the time. One of Lennon’s best-known songs about peace and love is titled Imagine.

Conclusion

Artistic expression documents, anticipates and translates what we experience in our world. Ideas of our identity, everyday life, our social interactions and the natural world around us become subject matter. Art of the past is a resource in understanding how different cultures use the visual language to explain shared experience. Some of the artworks are timeless and sustaining, others are gritty and challenging to look at. All leave footprints on the path we tread: our lives and our world.