Art Appreciation and Techniques/Module 5b

The following is an initial page plan for the module. The beginning text, before the colon, is the proposed page name.

- Overview: listing of what's included in unit

- Introduction: paragraph following list

- Early development:

- Impact on other media:

- Form and content:

- Darkroom processes:

- The human element:

- Color images:

- Photojournalism:

- Modern developments:

- Time-based media: Film, video and digital:

- Summary: conclusion

Contents

The Camera Arts

Introduction

This module provides an overview of the camera arts and how they’re used. They include:

· Film photography

· Photography’s impact on traditional media

· Issues of Form and Content

· Darkroom Processes

· The Human Element

· Color Images

· Photojournalism

· Modern Developments

· Digital photography

· Time-based mediums:

a) Motion pictures

b) Video

c) Digital streaming images

The invention of the camera and its ability to capture an image with light became the first “high tech” artistic medium of the Industrial Age. Developed during the middle of the nineteenth century, the photographic process changed forever our physical perception of the world and created an uneasy but important relationship between the photograph and other more traditional artistic media.

Early Development

The first attempts to capture an image were made from a camera obscura used since the 16th century. The device consists of a box or small room with a small hole in one side that acts as a lens. Light from an external scene passes through the hole and strikes the opposite surface inside where it is reproduced upside-down, but with color and perspective preserved. The image is usually projected onto paper adhered to the opposite wall, and can then be traced to produce a highly accurate representation. Experiments in capturing images on film had been conducted in Europe since the late 18th century. Using the camera obscura as a guide, early photographers found ways to chemically fix the projected images onto plates coated with light sensitive materials. Moreover, they installed glass lenses in their early cameras and experimented with different exposure times for their images. View from the Window at Le Gras is one of the oldest existing photographs, taken in 1826 by French inventor Joseph Niepce using a process he called heliograpy (“helio” meaning sun and “graph” meaning write). The exposure for the image took eight hours, resulting in the sun casting its light on both sides of the houses in the picture. Further developments resulted in apertures -- thin circular devices that are calibrated to allow a certain amount of light onto the exposed film (see the examples below). A wide aperture is used for low light conditions, while a smaller aperture is best for bright conditions. Apertures allowed photographers better control over their exposure times.

During the 1830’s, Louis Daguerre, having worked with Niepce earlier, developed a more reliable process to capture images on film by using a polished copper plate treated with silver. He termed the images made by this process “Daguerreotypes”. They were sharper in focus and the exposure times were shorter. His photograph Boulevard du Temp from 1838 is taken from his studio window overlooking a busy Paris street. Still, with an exposure of ten minutes, none of the moving traffic or pedestrians stayed still long enough to be recorded. The only person in the image is a man on the lower left, standing at the corner getting his shoes shined.

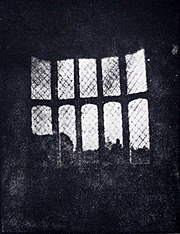

At the same time in England, William Henry Fox Talbot was experimenting with other photographic processes. He was creating photogenic drawings by simply placing objects (mostly botanical specimens) over light sensitive paper or plates, then exposing them to the sun. By 1844, he had invented the calotype; a photographic print made from a negative image. In contrast, Daguerreotypes were single, positive images that could not be reproduced. Talbot’s calotypes allowed for multiple prints from one negative, setting the standard for the new medium. “Latticed Window at Lacock Abbey” is a print made from the oldest photographic negative in existence.

Impact on Other Media

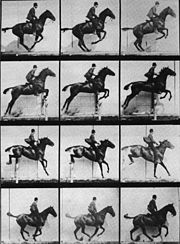

The advent of photography caused a realignment in the use of other two-dimensional media. The photograph was now in direct competition with drawing, painting and printmaking. The camera turns its gaze on the human narrative that stands before it. The photograph gave (for the most part), a realistic and unedited view of our world. It offered a more “true” image of nature because it’s manifest in light, not by the subjective hand and mind of the artist in their studio, which, depending on the style used, is open to manipulation. Its use as a tool for documentation was immediate, which gave the photo a scientific role to play. Talbot’s photogenic drawings of plant species became detailed documents for study, and the “freeze frame” photos of Eadweard Muybridge helped to understand human and animal movement. But the relative immediacy and improved clarity of the photographic image quickly pitted the camera against painting in the genre of portraiture. Before photography, painted portraits were afforded only to the wealthy and most prominent members of society. They became symbols of social class distinctions. Now portraits became available to individuals and families from all social levels. Let’s look at two examples from the different mediums to compare and contrast.

Gilbert Stuart’s painted portrait of Mrs. Oliver Brewster (Catherine Jones) (1815) not only records the sitter’s identity but also a psychological essence. There is a degree of informality in the work, as she leans forward in the chair, a shawl draped over one shoulder, hands clasped, with raised eyebrows and a slight smile on her lips. Her amusement is palpable and endearing.

In the photographic portrait of the English actress Ellen Terry, Julia Margaret Cameron captures the same informality and psychological complexities as Gilbert does, except this time the sitter leans against a patterned background, a simple white gown slips off her shoulders as she gently grasps a necklace with her right hand. Here the sitter’s gaze is cast downward, unsmiling, in a moment of reflection or sadness. The lighting, coming from the right, is used to dramatic effect as it illuminates the left side of Terry’s body but casts the right side in shadow.

One obvious difference is the lack of color in Cameron’s photo. Her use of black and white creates a graphic composition based on both dramatic and subtle changes in value. The first color photographs were developed as early as the 1860’s, but these early processes were impractical and of little value.

Painters worried that this new medium would spell the end to theirs. In reality, early photographers were influenced by popular styles of painting in creating their own compositions. Cameron’s staged photograph Queen Esther before King Ahasuerus from 1865 mimics the Symbolist paintings of the time in both style and subject matter. They used mythology, dramatic poses and other Romantic themes to create visual worlds with dream like figures and dark emotions. You can see the similarity between Cameron’s photograph and George Frederic Watts’ painting “Paolo and Francesca” from about the same time.

It didn’t take long for photographers to see the aesthetic value in the new medium. As early as 1844, Henry Talbot was taking pictures with a concern towards formal composition. The Open Door uses mundane subject matter to create a study in contrasts, visual balance and textures. The solid composition, anchored by the dark rectangle of the door and interior space book ended by sunlit areas, becomes animated with diagonals created in the heavy shadow cast on the door. The broom’s placement and its shadow reinforce this. Vines cropped on each side of the photo’s frame give balance, and the broom straw, stone work and door hardware create visual textures that enhance the effect. Finally, the lamp hanging near the right edge of the frame creates an accent that draws our eye.

Early photographs were made from single plates of metal, glass or paper, each one painstakingly prepared, exposed and developed. In 1884, George Eastman invented transparent roll film; strips of celluloid coated with a light-sensitive emulsion. Four years later, he developed the first hand held camera loaded with roll film. The combination brought access to photography within the reach of almost anyone. Additional advances were made in lens optics and shutter mechanics. By the turn of the nineteenth century, the photograph represented not only a new artistic medium but also a record -- and a symbol -- of the Industrial age itself.

Form and Content

The darkroom became the studio of the photographer. It was there where visual ideas translated into images: an opportunity to manipulate the film negative, to explore techniques and discover the potential the photograph had in interpreting objects and ideas.

Alfred Stieglitz understood this potential, and as a photographer, editor and gallery owner, was a major force in promoting photography as an art form. He led in forming the Photo Secession in 1902, a group of photographers who were interested in defining the photograph as an art form in itself, not just by the subject matter in front of the lens. Subject matter became a vehicle for an emphasis on composition, lighting and textural effects. His own photographs reflect a range of themes. The Terminal (1892) is an example of “straight photography”: images from the everyday taken with smaller cameras and little manipulation. In The Terminal, Stieglitz captures a moment of bustling city street life on a cold winter day. A massive stone façade looms in the background while a half-circle of horses and street wagons are led out of the picture to the right. The whole cold, gritty scene is softened by steam rising off the horses and the snow provides highlights. But the photo holds more than formal aesthetic value. The jumble of buildings, machines, humans, animals and weather conditions provides a glimpse into American urban culture straddling two centuries. Within ten years from the time this photo was taken, horses will be replaced by automobiles and subway stations will transform a large city’s movement into the twentieth century.

Other photographs by Stieglitz concentrate on more conceptual ideas. His series of cloud photos, called Equivalents, are efforts to record the essence of a particular reality, and to do it “so completely, that all who see [the picture of it] will relive an equivalent of what has been expressed”. His Equivalents photos establish a new level for the aesthetic content of ideas, and are essentially the first abstract photographs.

Darkroom Processes

The camera’s ability to capture a moment in time is not without difficulties. We’ve all had the experience where we declare “If I only had a camera with me!” On one hand, photographs taken in the studio are controlled productions, with the photographer working to find balances with lighting and composition. On the other hand, straight outdoor photography is unpredictable. Lighting and weather conditions change quickly, and so do the locations where the photographer will find that “one great shot”. To compensate for these variables, photographers typically take hundreds of pictures, bracketing shutter speeds and aperture settings as they go, then carefully editing each negative and print until they find the handful, or perhaps only the one, that will be the best image of them all.

The darkroom is where the exposed film is developed. It must be dark to eliminate any chance of outside light ruining the exposed film. In black and white film developing, a low-intensity red or amber colored lamp called a safe light is used so the photographer can see their way around during developing. The light emitted from the lamp is of a wavelength that does not affect exposure results.

Other tools used in a darkroom are typically an enlarger, an instrument with a lens and aperture in it that projects the image from a negative onto a base. Photographic paper is then placed under the projected image and exposed to light. The paper is put into a series of solutions that progressively start and stop the development of the positive photographic image. The development process gives the photographer another opportunity to manipulate the original image. Specific areas on the print can be exposed to more light (“burning” or darkening areas) or less light (“dodging” or lightening areas) in order to bring up details or create more dramatic visual effects. The image can also be cropped from its original size depending on how the photographer wants to present the final image.

Light meters are used to calibrate the amount of light available for a certain exposure. The photographer adjusts the aperture of the camera to allow for more or less light to fall on the film during the initial exposure. But light meters alone don’t guarantee the perfect photograph because they indicate the total amount of light, without respect to specific areas of light or dark within the format of the picture.

For this, the photographers Ansel Adams and Fred Archer created the zone system. The system relies on two interrelated factors – the visualization of how the photographer wants the print to look even before they take it, and a correct light calibration from all the areas by assigning numbers to different brightness values – or ‘zones’ on the value scale, from white to black and all the various gray tones in between. The zone system is tedious both in the field and in the darkroom, but, since its inception in 1940, has spurred creation of photographs absolutely stunning in their clarity, composition and graphic drama. Adams’ Taos Pueblo below is an example.

The Human Element

Photography became the most contemporary of artistic media, one particularly suited to record the human dramas being played out in an increasingly modern world. French photographer Robert Doisneau’s The Kiss on the Sidewalk from 1950 shows a romantic kiss as an oasis in the middle of a busy Paris sidewalk. That the photo was not spontaneous but a reenactment takes nothing away from the emotional content: Paris as the city of Love. Eugene Atget (pronounced “Ah-jay”) (1856-1927) was one of the first to use the photograph as a cultural and social document. His images of Paris and its surroundings give poetic witness to the buildings, people and scenes that inhabit and define the city.

The work of Diane Arbus (1923-1971) challenges us as we gaze at others who are deviant, marginalized or stand out because of the context in which we see their normality. Arbus’ lens is unflinching in its honesty. She presents images of strangeness and alienation without condescension or judgment. It’s up to us to try to fill in the blanks.

Many of the photographs in Robert Frank’s series, The Americans, depicts groups of people in different situations, including riding a bus, watching a rodeo and listening to a speech. His photo essay on American life is seen through the eyes of an observer, not a participant. Instead of voyeuristic, they give a sense of detachment. Only a few of the figures look directly into the camera or directly at other people in the photo. Frank worked hard to maintain the observer’s point of view. Similar to Arbus, the photographs carry overtones of alienation – between the individual and the group. Controversial when first published in the United States in 1959, the book now is seen as one of the most important modern photographic social commentaries.

Color Images

The wider use of color film after 1935 added another dimension to photography. Color can give a stronger sense of reality: the photo looks much like the way we actually see the scene with our eyes. Moreover, the use of color affects the viewer’s perception, triggering memory and reinforcing visual details. Photographers can manipulate color and its effects either before or after the picture is taken.

Even though there is no figure present in Grand Canyon, 1973, we observe the landscape through the eyes of the photographer. Joel Meyerowitz makes use of raking light and two sets of complementary colors; orange and blue, yellow and violet giving stark contrast and vibrancy to the photograph. The foreground, bathed in warm light, has details and patterns created by the scrub brush dotting the hill. A bright yellow spike plant rises up out of the desert like a beacon, an exclamation point on a vast, barren landscape. The cool blues and purples in the background soften the plateaus and hills as they disappear on the horizon.

In a final example, the finely meshed screen sporting flies in the foreground dilutes and blurs a warm monochromatic color scheme in Irving Penn’s Summer Sleep (1949). Distortion in the center of the photo takes on a blue hue, visually hovering like a mist over the sleeping figure in the background. For its seemingly informal set up, Penn’s photo is actually a meticulously arranged composition. And the narrative is just as meticulously crafted: serene, gauzy sleep within while trouble waits just beyond.

Photojournalism

The news industry was fundamentally changed with the invention of the photograph. Although pictures were taken of newsworthy stories as early as the 1850’s, the photograph needed to be translated into an engraving before being printed in a newspaper. It wasn’t until the turn of the nineteenth century that newspaper presses could copy original photographs. Photos from around the world showed up on front pages of newspapers defining and illustrating stories, and the world became smaller as this early mass medium gave people access to up to date information…with pictures!

Photojournalism is a particular form of journalism that creates images in order to tell a news story and is defined by these three elements:

- Timeliness— the images have meaning in the context of a recently published record of events.

- Objectivity— the situation implied by the images is a fair and accurate representation of the events they depict in both content and tone.

- Narrative— the images combine with other news elements to make facts relatable to the viewer or reader on a cultural level.

As visual information, news images help in shaping our perception of reality and the context surrounding them.

Photographs taken by Mathew Brady, Timothy O'Sullivan and others photographers during the American Civil War (below) gave sobering witness to the carnage it produced. Images of soldiers killed in the field help people realize the human toll of war and desensitize their ideas of battle as being particularly heroic.

Sometimes soldiers themselves take photographs in the battlefield. In the picture below, Robert F. Sargent, a Chief Photographer’s Mate in the U.S. Coast Guard, gives an eyewitness visual account of Allied troops coming ashore in France on D-Day, 1944.

Photojournalism’s “Golden Age” took place between 1930 and 1950, coinciding with advances in the mediums of radio and television. Margaret Bourke-White’s photographs helped define the standards of photojournalism. Her work with Life magazine and as the first female war correspondent in Europe produced indelible images of the rise of industry, the effects of the Dust Bowl, the Great Depression and World War Two. Ammonia Storage Tanks (1930) shows masterful composition as she gets four of the massive tanks into the picture. The shadows, industrial grids of metalwork and the inclusion of figures at the top for an indication of scale make a powerful visual statement about the modern industrial landscape. One of her later photographs, A Mile Underground, Kimberly Diamond Mine, South Africa from 1950 frames two black mine workers staring back at the camera lens, their heads high with looks of resigned determination on their faces.

Dorothea Lange was employed by the federal government’s Farm Security Administration to document the plight of migrant workers and families dislocated by the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression In America during the 1930’s. Migrant Mother, Nipomo Valley, California is an iconic image of its hardships and the human resolve to survive. Like O’Sullivan’s civil war photos, Lange’s picture puts a face on human tragedy. Photographs like this helped win continued support for president Franklin Roosevelt’s social aid programs.

Photojournalism does not always find the story in far away places. More often it is in the urban settings of big cities. Weegee (born Arthur Fellig) made a living as a ubiquitous news photographer on the streets of New York City. He documented the sensational, from murders to entertainment, and kept a police radio in his car so as to be the first on the scene of the action. His photo Simply Add Boiling Water from 1937 shows the Hygrade frankfurter building in flames while firemen spray water into it. The photo’s title is ironic and taken from the sign across the center of the building.

Modern Developments

Edwin Land invented the instant camera, capable of taking and developing a photograph, in 1947, followed by the popular SX-70 instant camera in 1972. The SX-70 produced a 3” square-format positive image that developed in front of your eyes. The beauty of instant development for the artist was that during the two or three minutes it took for the image to appear, the film emulsion stayed malleable and able to manipulate. The artist Lucas Samaras used this technique of manipulation to produce some of the most imaginative and visually perplexing images in a series he termed photo-transformations. Using himself as subject, Samaras explores ideas of self-identity, emotional states and the altered reality he creates on film.

Digital cameras appeared on the market in the mid 1980’s. They allow the capture and storage of images through electronic means (the charge-coupled device) instead of photographic film. This new medium created big advantages over the film camera: the digital camera produces an image instantly, stores many images on a memory card in the camera, and the images can be downloaded to a computer, where they can be further manipulated by editing software and sent anywhere through cyberspace. This eliminated the time and cost involved in film development and created another revolution in the way we access visual information.

Digital images start to replace those made with film while still adhering to traditional ideas of design and composition. The image you see below is a photograph of the Golden Gate Bridge that has been retouched to create light effects traditionally used in paintings. The photograph also uses many of the artistic elements and principles that you learned about in Unit 3 in its composition.

In addition, digital cameras and editing software let artists explore the notion of staged reality: not just recording what they see but creating a new visual reality for the viewer. Sandy Skogland creates and photographs elaborate tableaus inhabited by animals and humans, many times in cornered, theatrical spaces. In a series of images titled True Fiction Two she uses the digital process – and the irony in the title to build fantastically colored, dream like images of decidedly mundane places. By straddling both installation and digital imaging, Skoglund blurs the line between the real and the imagined in art.

The photographs of Jeff Wall are similar in content – a blend of the staged and the real, but present them selves in a straightforward style the artist terms as “near documentary”.

Time-based media: Film, Video and Digital

With traditional film, what we see as a continuous moving image is actually a linear progression of still photos on a single reel that pass through a lens at a certain rate of speed and are projected onto a screen. We saw a simple form of this process earlier in the pioneering work of Eadweard Muybridge.

The first motion picture cameras were invented in Europe during the late nineteenth century. These early “movies” lacked a soundtrack and were normally shown along with a live pianist, organ player or orchestra in the theatre to provide the musical accompaniment. In the United States, film went from being a novelty to an art form with D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation in 1915. In it Griffith presents a narrative of the Civil War and its aftermath but with a decidedly racist view of American blacks and the Ku Klux Klan.

Film scholars agree, however, that it is the single most important and key film of all time in American movie history - it contains many new cinematic innovations and refinements, technical effects and artistic advancements, including a color sequence at the end. It had a formative influence on future films and has had a recognized impact on film history and the development of film as art. In addition, at almost three hours in length, it was the longest film to date (From Filmsite Movie Review: The Birth of a Nation).

Unique to the moving image is its ability to unfold an idea or narrative over time, using the same elements and principles inherent in any artistic medium. Film stills show how dramatic use of lighting, staging and set compositions are embedded throughout an entire film (for formal comparisons, see the work of Cindy Sherman above).

Video art, first appearing in the 1960’s and 70’s, uses magnetic tape to record image and sound together. The advantage of video over film is its instant playback and editing capability. One of the pioneers in using video as an art form was Doris Chase. She began by integrating her sculptures with interactive dancers, using special effects to create dreamlike work, and spoke of her ideas in terms of painting with light. Unlike filmmakers, video artists frequently combine their medium with installation, an art form that uses entire rooms or other specific spaces, to achieve effects beyond mere projection. South Korean video artist Nam June Paik made breakthrough works that comment on culture, technology and politics. Contemporary video artist Bill Viola creates work that is more painterly and physically dramatic, often training the camera on figures within a staged set or spotlighted figures in dark surroundings as they act out emotional gestures and expressions in slow motion. Indeed, his work The Greeting reenacts the emotional embrace seen in the Italian Renaissance painter Jocopo Pontormo’s work The Visitation below.

Computers and digital technology have, like the camera did over one hundred and fifty years ago, revolutionized the visual art landscape. Some artists now use digital technology to extend the reach of creative possibilities. Sophisticated software allows any computer user the opportunity to create and manipulate images and information. From still images and animation to streaming digital content and digital installations, computers have become high tech creative tools.

In a blending of traditional and new media, artist Chris Finley uses digital templates – software based composition formats – to create his paintings. The work of German artist Jochem Hendricks combines digital technology and human sight. His eye drawings rely on a computer interface to translate the process of looking into physical drawings.

Digital technology is a big part of the video and motion picture industries with the capability for high definition images, better editing resources and more areas for exploration to the artist.

Conclusion

The camera arts are relatively new mediums to the world of art but their contributions are perhaps the most significant of all. They are certainly the most complex. Like traditional mediums of drawing, painting and sculpture they allow creative exploration of ideas and the making of objects and images. The difference is in their avenue of expression: by recording images and experiences through light and electronics they, on the one hand, narrow the gap between the worlds of the ‘real’ and the ‘imagined’ and on the other offers us an art form that can invent its own reality with the inclusion of the dimension of time. We watch as a narrative unfolds in front of our eyes. Digital technology has created a whole new kind of spatial dimension: cyberspace.