Art Appreciation and Techniques/Module 5

The following is an initial page plan for the module. The beginning text, before the colon, is the proposed page name.

- Overview: introduction and objectives

- Introduction: the first paragraph below main header

- Drawing:

- Painting:

- Printmaking:

- Collage:

- Summary: Conclusion

Module 5: Artistic Media and Action

Attributed to Saylor.org(adapted).

Module 5 Description

Artists find ways to express themselves with almost anything available. It is a stamp of their creativity to make extraordinary images and objects from various but fairly ordinary materials. From thread, string and stone to paint, ink, plant life, steel and now electronics and digital media, artists continue to search for ways to construct and deliver their message.

Upon successful completion of this unit, you will be able to:

|

Introduction

This module explores traditional and non-traditional mediums associated with two-dimensional artworks including drawing, painting, printmaking and collage. Two-dimensional media includes those that are delivered to a flat surface, with only height and width for their measurement and are grouped into general categories. Let's look at each group to understand their particular qualities and how artists use them.

Drawing

Drawing is the simplest and most efficient way to communicate visual ideas, and for centuries charcoal, chalk, graphite and paper have been adequate enough tools to launch some of the most profound images in art. Leonardo da Vinci’s The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and Saint John the Baptist wraps all four figures together in what is essentially an extended family portrait. Da Vinci draws the figures in a spectacularly realistic style, one that emphasizes individual identities and surrounds the figures in a grand, unfinished landscape. He animates the scene with the Christ child pulling himself forward, trying to release himself from Mary’s grasp to get closer to a young John the Baptist on the right, who himself is turning toward the Christ child with a look of curious interest in his younger cousin.In fact, the traditional role of drawing was to make sketches for larger compositions to be manifest as paintings, sculpture or even architecture. Because of its relative immediacy, this function for drawing continues today. A preliminary sketch by the contemporary architect Frank Gehry captures the complex organic forms of the buildings he designs.

Types of Drawing Media

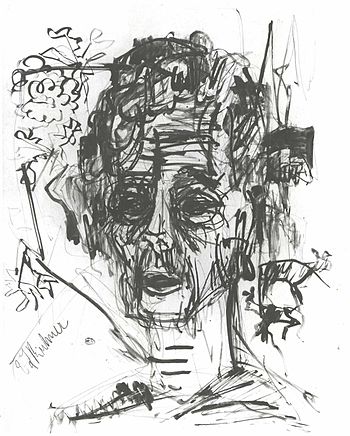

Dry Media includes charcoal, graphite, chalks and pastels. Each of these mediums gives the artist a wide range of mark making capabilities and effects, from thin lines to large areas of color and tone. The artist manipulates the medium to achieve desired effects by exerting different pressure on the medium against the drawing’s surface, or by erasure or blotting. The process of drawing instantly transfers a character to the image. From energetic to subtle, these qualities are apparent in the simplest works: the immediate and unalloyed spirit of the artist’s idea. You can see this in the self-portraits of two German artists; Kathe Kollwitz and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. His Self-Portrait Under the Influence of Morphine from about 1916 presents us with a nightmarish vision of himself wrapped in the fog of opiate drugs. His hollow eyes and the graphic dysfunction of his marks attest to the power of his drawing.

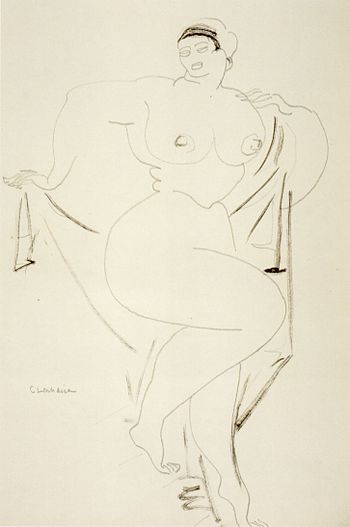

Graphite media includes pencils, powder or compressed sticks. Each one creates a range of values depending on the hardness or softness inherent in the material. Hard graphite tones range from light to dark gray, while softer graphite allows a range from light gray to nearly black. French sculptor Gaston Lachaise’s Standing Nude with Drapery is a pencil drawing that fixes the energy and sense of movement of the figure to the paper in just a few strokes. And Steven Talasnik’s contemporary large- scale drawings in graphite, with their swirling, organic forms and architectural structures are testament to the power of pencil (and eraser) on paper.

Charcoal, perhaps the oldest form of drawing media, is made by simply charring wooden sticks or small branches, called vine charcoal, but is also available in a mechanically compressed form. Vine charcoal comes in three densities: soft, medium and hard, each one handling a little different than the other. Soft charcoals give a more velvety feel to a drawing. The artist doesn’t have to apply as much pressure to the stick in order to get a solid mark. Hard vine charcoal offers more control but generally doesn’t give the darkest tones. Compressed charcoals give deeper blacks than vine charcoal, but are more difficult to manipulate once they are applied to paper.

Charcoal drawings range in tones from light gray to rich, velvety blacks. A charcoal drawing by American artist Georgia O’Keeffe shows these tonal ranges.

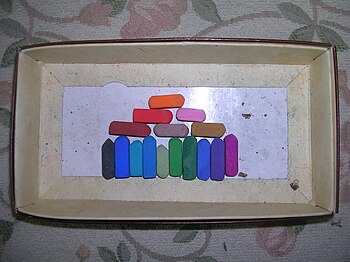

Pastels are essentially colored chalks usually compressed into stick form for better handling. They are characterized by soft, subtle changes in tone or color. Pastel pigments allow for a resonant quality that is more difficult to obtain with graphite or charcoal. Picasso’s Portrait of the Artist's Mother from 1896 emphasizes these qualities.

More recent developments in dry media are oil pastels, pigment mixed with an organic oil binder that deliver a heavier mark and lend themselves to more graphic and vibrant results. The drawings of Beverly Buchanan reflect this. Her work celebrates rural life of the south centered in the forms of old houses and shacks. The buildings stir memories and provide a sense of place, and are usually surrounded by people, flowers and bright landscapes. She also creates sculptures of the shacks, giving them an identity beyond their physical presence.

Wet media traditionally refers to ink but really includes any substance that can be put into solution and applied to a drawing’s surface. Because wet media is manipulated much like paint – through thinning and the use of a brush – it blurs the line between drawing and painting. Ink can be applied with a stick for linear effects and by brush to cover large areas with tone. It can also be diluted with water to create values of gray. The Return of the Prodigal Son by Rembrandt shows an expressive use of brown ink in both the line qualities and the larger brushed areas that create the illusion of light and shade.

Felt tip pens are considered a form of wet media. The ink is saturated into felt strips inside the pen then released onto the paper or other support through the tip. The ink quickly dries, leaving a permanent mark. The colored marker drawings of Donnabelle Casis have a flowing, organic character to them. The abstract quality of the subject matter infers body parts and viscera.

Other liquids can be added to drawing media to enhance effects – or create new ones. Artist Jim Dine has splashed soda onto charcoal drawings to make the surface bubble with effervescence. The result is a visual texture unlike anything he could create with charcoal alone, although his work is known for its strong manipulation. Dine’s drawings often use both dry and liquid media. His subject matter includes animals, plants, figures and tools, many times crowded together in dense, darkly romantic images.

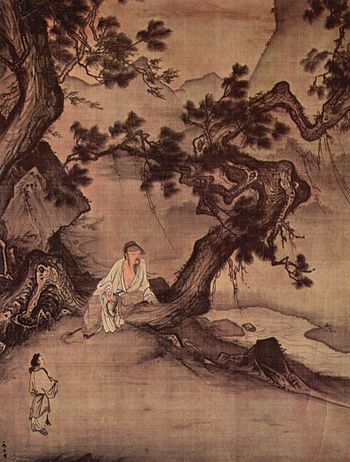

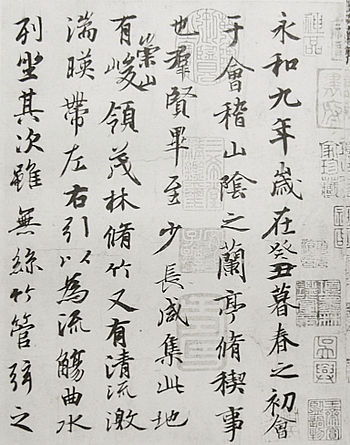

Traditional Chinese painting uses water-based inks and pigments. In fact, it is one of the oldest continuous artistic traditions in the world. Painted on supports of paper or silk, the subject matter includes landscapes, animals, figures and calligraphy, an art form that uses letters and script in fluid, lyrical gestures. Two examples of traditional Chinese painting are seen below. The first, a wall scroll painted by Ma Lin in 1246, demonstrates how adept the artist is in using ink in an expressive form to denote figures, robes and landscape elements, especially the strong, gnarled forms of the pine trees. There is sensitivity and boldness in the work. The second example is the opening detail of a copy of "Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion" made before the 13th century. Using ink and brush, the artist makes language into art through the sure, gestural strokes and marks of the characters.

Drawing is a foundation for other two and three-dimensional works of art, even being incorporated with digital media that expands the idea of its formal expression. The art of Matthew Ritchie starts with small abstract drawings. He digitally scans and projects them to large scales, taking up entire walls. Ritchie also uses the scans to produce large, thin three-dimensional templates to create sculptures out of the original drawings.

Painting

Painting is the application of pigments to a support surface that establishes an image, design or decoration. In art the term ‘painting’ describes both the act and the result. Most painting is created with pigment in liquid form and applied with a brush. Exceptions to this are found in Navajo sand painting and Tibetan mandala painting, where powdered pigments are used.

Three of the most recognizable images in Western art history are paintings: Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, Edvard Munch’s The Scream and Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night. These three art works are examples of how painting can go beyond a simple mimetic function, that is, to only imitate what is seen. The power in great painting is that it transcends perceptions to reflect emotional, psychological, even spiritual levels of the human condition. Painting as a medium has survived for thousands of years and is, along with drawing and sculpture, one of the oldest creative mediums. It’s used in some form by cultures around the world.

Painting mediums are extremely versatile because they can be applied to many different surfaces (called supports) including paper, wood, canvas, plaster, clay, lacquer and concrete. Because paint is usually applied in a liquid or semi-liquid state it has the ability to soak into porous support material, which can, over time, weaken and damage the it. To prevent this a support is usually first covered with a ground, a mixture of binder and chalk that, when dry, creates a non-porous layer between the support and the painted surface. A typical ground is gesso.

There are six major painting mediums, each with specific individual characteristics.They are encaustic, tempera, fresco, oil, acrylic and watercolor. All of them use three basic ingredients: pigment, binder, and solvent.

Pigments are granular solids incorporated into the paint to contribute color. The binder, commonly referred to as the vehicle, is the actual film-forming component of paint. The binder holds the pigment in solution until it’s ready to be dispersed onto the surface. The solvent controls the flow and application of the paint. It’s mixed into the paint, usually with a brush, to dilute it to the proper viscosity, or thickness, before it’s applied to the surface. Once the solvent has evaporated from the surface the remaining paint is fixed there. Solvents range from water to oil-based products like linseed oil and mineral spirits.

Let's look at the main painting mediums:

1. Encaustic paint mixes dry pigment with a heated beeswax binder. The mixture is then brushed or spread across a support surface. Reheating allows for longer manipulation of the paint. Encaustic dates back to the first century C.E. and was used extensively in funerary mummy portraits from Fayum in Egypt. The characteristics of encaustic painting include strong, resonant colors and extremely durable paintings. Because of the beeswax binder, when encaustic cools it forms a tough skin on the surface of the painting.

Encaustic painting has seen resurgence in use since the 1990’s. Below is a recent example of an encaustic piece from 2009.

Modern electric and gas tools allow for extended periods of heating and paint manipulation.

2. Tempera paint combines pigment with an egg yolk binder, then thinned and released with water. Like encaustic, tempera has been used for thousands of years. It dries quickly to a durable matte finish. Tempera paintings are traditionally applied in successive thin layers, called glazes, painstakingly built up using networks of cross hatched lines. Because of this technique tempera paintings are known for their detail.

In early Christianity, tempera was used extensively to paint images of religious icons. The pre-Renaissance Italian artist Duccio (c. 1255 – 1318), one of the most influential artists of the time, used tempera paint in the creation of The Crevole Madonna (above). You can see the sharpness of line and shape in this well-preserved work, and the detail he renders in the face and skin tones of the Madonna.

Contemporary painters still use tempera as a medium. American painter Andrew Wyeth (1917-2009) used tempera to create Christina's World, a masterpiece of detail, composition and mystery. The image can be found here.

3. Fresco painting is used exclusively on plaster walls and ceilings. The medium of fresco has been used for thousands of years, but is most associated with its use in Christian images during the Renaissance period in Europe.

There are two forms of fresco: Buon or “wet”, and secco, meaning “dry”. Buon fresco technique consists of painting in pigment mixed with water on a thin layer of wet, fresh lime mortar or plaster. The pigment is applied to and absorbed by the wet plaster; after a number of hours, the plaster dries and reacts with the air: it is this chemical reaction that fixes the pigment particles in the plaster. Because of the chemical makeup of the plaster, a binder is not required. Buon fresco is more stable because the pigment becomes part of the wall itself.

Domenico di Michelino’s Dante and the Divine Comedy from 1465 (below) is a superb example of buon fresco. The colors and details are preserved in the dried plaster wall. Michelino shows the Italian author and poet Dante Aleghieri standing with a copy of the Divine Comedy open in his left hand, gesturing to the illustration of the story depicted around him. The artist shows us four different realms associated with the narrative: the mortal realm on the right depicting Florence, Italy; the heavenly realm indicated by the stepped mountain at the left center – you can see an angel greeting the saved souls as they enter from the base of the mountain; the realm of the damned to the left – with Satan surrounded by flames greeting them at the bottom of the painting; and the realm of the cosmos arching over the entire scene.

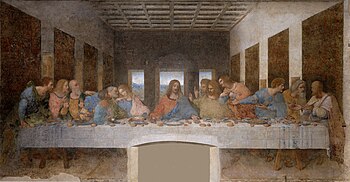

Secco fresco refers to painting an image on the surface of a dry plaster wall. This medium requires a binder since the pigment is not mixed into the wet plaster. Egg tempera is the most common binder used for this purpose. It was common to use secco fresco over buon fresco murals in order to repair damage or make changes to the original. Leonardo Da Vinci’s painting of The Last Supper (below) was done using secco fresco.

4. Oil paint is the most versatile of all the painting mediums. It uses pigment mixed with a binder of linseed oil. Linseed oil can also be used as the vehicle, along with mineral spirits or turpentine. Oil painting was thought to have developed in Europe during the 15th century, but recent research on murals found in Afghanistan caves show oil based paints were used there as early as the 7th century.

Some of the qualities of oil paint include a wide range of pigment choices, its ability to be thinned down and applied in almost transparent glazes as well as used straight from the tube (without the use of a vehicle), built up in thick layers called impasto (you can see this in many works by Vincent van Gogh). One drawback to the use of impasto is that over time the body of the paint can split, leaving networks of cracks along the thickest parts of the painting. Because oil paint dries slower than other mediums, it can be blended on the support surface with meticulous detail. This extended working time also allows for adjustments and changes to be made without having to scrape off sections of dried paint.

In Jan Brueghel the Elder’s still life oil painting you can see many of the qualities mentioned above. The richness of the paint itself is evident in both the resonant lights and inky dark colors of the work. The working of the paint allows for many different effects to be created, from the softness of the flower petals to the reflection on the vase and the many visual textures in between.

Richard Diebenkorn’s Street from 1961 shows how the artist uses oil paint in a more fluid, expressive manner. He thins down the medium to obtain a quality and gesture that reflects the sunny, breezy atmosphere of a California morning. Diebenkorn used layers of oil paint, one over the other, to let the under painting show through and a flat, more geometric space that blurs the line between realism and abstraction. This image can be found here.

Georgia O’Keeffe’s oil paintings show a range of handling between soft and austere to very detailed and evocative. You rarely see her brushstrokes, but she has a summary command of the medium of oil paint.

The abstract expressionist painters pushed the limits of what oil paint could do. Their focus was in the act of painting as much as it was about the subject matter. Indeed, for many of them there was no distinction between the two. The work of Willem de Kooning leaves a record of oil paint being brushed, dripped, scraped and wiped away all in a frenzy of creative activity. This idea stays contemporary in the paintings of Celia Brown.

5. Acrylic paint was developed in the 1950’s and became an alternative to oils. Pigment is suspended in an acrylic polymer emulsion binder and uses water as the vehicle. The acrylic polymer has characteristics like rubber or plastic. Acrylic paints offer the body, color resonance and durability of oils without the expense, mess and toxicity issues of using heavy solvents to mix them. One major difference is the relatively fast drying time of acrylics. They are water soluble, but once dry become impervious to water or other solvents. Moreover, acrylic paints adhere to many different surfaces and are extremely durable. Acrylic impastos will not crack or yellow over time.

The American artist Robert Colescott (1925-2009) used acrylics on large-scale paintings. He uses thin layers of under painting, scumbling, high contrast colors and luscious surfaces to bring out the full range of effects that acrylics offer.

6. Watercolor is the most sensitive of the painting mediums. It reacts to the lightest touch of the artist and can become an over worked mess in a moment. There are two kinds of watercolor media: transparent and opaque. Transparent watercolor operates in a reverse relationship to the other painting mediums. It is traditionally applied to a paper support, and relies on the whiteness of the paper to reflect light back through the applied color (see below), whereas opaque paints (including opaque watercolors) reflect light off the skin of the paint itself. Watercolor consists of pigment and a binder of gum arabic, a water-soluble compound made from the sap of the acacia tree. It dissolves easily in water.

Watercolor paintings hold a sense of immediacy. The medium is extremely portable and excellent for small format paintings. The paper used for watercolor is generally of two types: hot pressed, which gives a smoother texture, and cold pressed, which results in a rougher texture. Transparent watercolor techniques include the use of wash, an area of color applied with a brush and diluted with water to let it flow across the paper. Wet-in-wet painting allows colors to flow and drift into each other, creating soft transitions between them. Dry brush painting uses little water and lets the brush run across the top ridges of the paper, resulting in a broken line of color and lots of visual texture.

Examples of watercolor painting techniques can be found as follows: Wash- click here; Dry Brush- Click here

John Marin’s Brooklyn Bridge (1912) shows extensive use of wash. He renders the massive bridge almost invisible except for the support towers at both sides of the painting. Even the Manhattan skyline becomes enveloped in the misty, abstract shapes created by washes of color.

“Boy in a Red Vest” by French painter Paul Cezanne builds form through nuanced colors and tones. The way the watercolor is laid onto the paper reflects a sensitivity and deliberation common in Cezanne’s paintings.

The watercolors of Andrew Wyeth indicate the landscape with earth tones and localized color, often with dramatic areas of white paperleft untouched. Brandywine Valley is a good example.

Opaque watercolor, also called gouache, differs from transparent watercolor in that the particles are larger, the ratio of pigment to water is much higher, and an additional, inert, white pigment such as chalk is also present. Because of this, gouache paint gives stronger color than transparent watercolor, although it tends to dry to a slightly lighter tone than when it is applied. Gouache paint doesn’t hold up well as impasto, tending to crack and fall away from the surface. It holds up well in thinner applications and often is used to cover large areas with color. Like transparent watercolor, dried gouache paint will become soluble again in water.

Jacob Lawrence’s Builders #2 uses gouache to set the design of the composition. Large areas of color – including the complements blue and orange, dominate the figurative shapes in the foreground, while olive greens and neutral tones animate the background with smaller shapes depicting tools, benches and tables. The characteristics of gouache make it difficult to be used in areas of detail.

Gouache is a medium in traditional painting from other cultures too. Zal Consults the Magi, part of an illuminated manuscript form 16th century Iran, uses bright colors of gouache along with ink, silver and gold to construct a vibrant composition full of intricate patterns and contrasts. Ink is used to create lyrical calligraphic passages at the top and bottom of the work.

Other painting mediums used by artists include the following:

Enamel paints form hard skins typically with a high-gloss finish. They use heavy solvents and are extremely durable.

Powder coat paints differ from conventional paints in that they do not require a solvent to keep the pigment and binder parts in suspension. They are applied to a surface as a powder then cured with heat to form a tough skin that is stronger than most other paints. Powder coats are applied mostly to metal surfaces.

Epoxy paints are polymers, created mixing pigment with two different chemicals: a resin and a hardener. The chemical reaction between the two creates heat that bonds them together. Epoxy paints, like powder coats and enamel, are extremely durable in both indoor and outdoor conditions.

These industrial grade paints are used in sign painting, marine environments and aircraft painting.

Printmaking

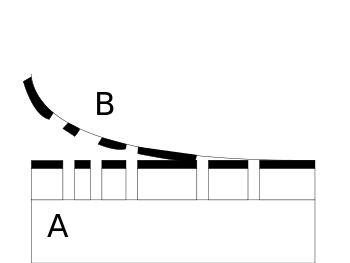

Printmaking uses a transfer process to make multiples from an original image or template. The multiple images are printed in an edition, with each print signed and numbered by the artist. All printmaking mediums result in images reversed from the original. Print results depend on how the template (or matrix) is prepared. There are three basic techniques of printmaking: Relief, Intaglio and Planar. You can get an idea of how they differ from the cross-section images below, and view how each technique works from this site at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

The black areas indicate the inked surface.

A relief print, such as a woodcut or linoleum cut, is created when the areas of the matrix (plate or block) that are to show the printed image are on the original surface; the parts of the matrix that are to be ink free having been cut away, or otherwise removed. Thus, the printed surface is in relief from the cut away sections of the plate. Once the area around the image is cut away, the surface of the plate is rolled up with ink. Paper is laid over the matrix, and both are run through a press, transferring the ink from the surface of the matrix to the paper. The nature of the relief process doesn’t allow for lots of detail, but does result in graphic images with strong contrasts. Carl Eugene Keel’s “Bar” shows the effects of a woodcut printed in black ink.

Relief printmaking was borne of block printing, developed in China hundreds of years ago. The medium spread to Japan, where ukiyo-e or “floating world” prints became popular in the 19th century, even influencing European artists during the Industrial Revolution.

Relief printmakers can use a separate block or matrix for each color printed. In reduction prints a single block is used, cutting away areas of color as the print develops. This method can result in a print with many colors.

Examples of reduction woodblock prints can be found here.

Intaglio Printing

Intaglio prints such as etchings, are made by incising channels into a copper or metal plate with a sharp instrument called a burin to create the image, inking the entire plate, then wiping the ink from the surface of the plate, leaving ink only in the incised channels below the surface. Paper is laid over the plate and put through a press under high pressure, forcing the ink to be transferred to the paper.

Examples of the intaglio process include dry point: The artist creates an image by scratching the burin directly into a metal plate (usually copper), without etching the plate before printing. Characteristically these prints have strong line quality and exhibit a slightly blurred edge to the line as the result of burrs created in the process of incising the plate, similar to clumps of soil laid to the edge of a furrowed trench. A fine example of dry point is seen in Rembrandt’s Clump of Trees with a Vista. The velvety darks are created by the effect of the burred-edged lines.

Etched Printing

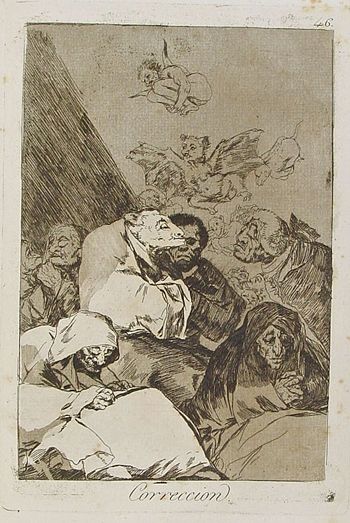

Etching begins by scratching an image with a burin through a protective coating into a thin metal plate. The plate is submersed in a strong acid bath, etching the exposed lines. The plate is removed from the acid and the protective coating is removed from the plate. Now the bare plate is inked, wiped and printed. The image is created from the ink in the etched channels. The amount of time a plate is kept in the acid bath determines the quality of tones in the resulting print: the longer it is etched the darker the tones will be. ‘Correccion’ (Correction) by the Spanish master Francisco Goya shows the clear linear quality etching can produce. The acid bath removes any burrs created by the initial dry point work, leaving details and value contrasts consistent with the amount of lines and the distance between them. Goya presents a fantastic image of people, animals and strange winged creatures. His work often involved biting social commentary. ‘Correccion’ is a contrast between the pious and the absurd.

There are many different techniques associated with intaglio, including aquatint, scraping and burnishing.

Planar Printing

Planar prints like monoprints are created on the surface of the matrix without any cutting or incising. In this technique the surface of the matrix (usually a thin metal plate or Plexiglass) is completely covered with ink, then areas are partially removed by wiping, scratching away or otherwise removed to form the image. Paper is laid over the matrix, then run through a press to transfer the image to the paper. Monoprints (also monotypes) are the simplest and painterly of the printing mediums. By definition monotypes and monoprints cannot be reproduced in editions. Kathryn Trigg’s monotypes show how close this print medium is related to painting and drawing.

Lithography is another example of planar printmaking, developed in Germany in the late 18th century. “Litho” means “stone” and “graph” means “to draw”. The traditional matrix for lithography is the smooth surface of a limestone block.

While this matrix is still used extensively, thin zinc plates have also been introduced to the medium. They eliminate the bulk and weight of the limestone block but provide the same surface texture and characteristics. The lithographic process is based on the fact that grease repels water. In traditional lithography, an image is created on the surface of the stone or plate using grease pencils or wax crayons or a grease-based liquid medium called tusche. The finished image is covered in a thin layer of gum arabic that includes a weak solution of nitric acid as an etching agent. The resulting chemical reaction divides the surface into two areas: the positive areas containing the image and that will repel water, and the negative areas surrounding the image that will be water receptive. In printing a lithograph, the gum arabic film is removed and the stone or metal surface is kept moist with water so when it’s rolled up with an oil based ink the ink adheres to the positive (image) areas but not to the negative (wet) areas.

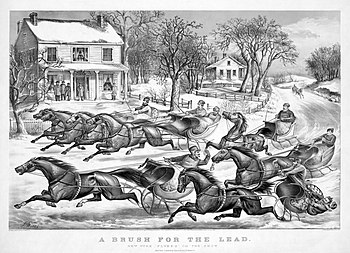

Because of the mediums used to create the imagery, lithographic images show characteristics much like drawings or paintings. In “A Brush for the Lead” by Currier And Ives, a full range of shading and more linear details of description combine to illustrate a winter’s race down the town’s main road. Another lithographic process is offset lithography, used commercially to print newspapers and magazines.

Serigraphy,also known as Screen printing, is a third type of planar printing medium. Screen printing is a printing technique that uses a woven mesh to support an ink-blocking stencil. The attached stencil forms open areas of mesh that transfer ink or other printable materials that can be pressed through the mesh as a sharp-edged image onto a substrate such as paper or fabric. A roller or squeegee is moved across the screen stencil, forcing or pumping ink past the threads of the woven mesh in the open areas. The image below shows how a stencil’s positive (image) areas are isolated from the negative (non-image) areas.

In serigraphy, each color needs a separate stencil. You can watch how this process develops in the accompanying video. Screen printing is an efficient way to print posters, announcements and other kinds of popular culture images. Andy Warhol’s silk screens use images and iconography from popular culture only to represent them as works of fine art.

Collage

Collage is a medium that uses found objects or images such as newspaper or other printed material, illustrations, photographs, even string or fabric, to create images. It also refers to works of art (paintings, drawings and prints) that include pieces of collage within them. Collage was made popular in western art history by Pablo Picasso and the cubists. The German artist Kurt Schwitters used collage as the dominant formal element in his works from the 1930’s. His work Opened by Customs is an excellent example of the importance of collage to the modern art movement in Europe before World War Two.

Artist Romare Bearden used collage to comment on urban life and the black experience in America. His Patchwork Quilt presents us with a figure in profile reminiscent of Egyptian painting. The starkness of the black figure surrounded by a collage of patterned fabric and dark background color creates a shallow space and dynamic composition.

The Japanese American artist Paul Horiuchi began as a painter but by mid career used collage almost exclusively. Mesa from 1960 is an abstract rendition of the geologic feature: an isolated hill with steeply sloping sides and a flat top (compare it to Joseph Goldberg’s “Spring Mesa” above in the encaustic painting section). Horiuchi’s art is a successful blending of the formal elements of cubist ideas with the oriental aesthetic of his Japanese heritage. His most ambitious piece is the Seattle Mural, a huge glass mosaic commissioned for the site of the1962 World’s Fair.

The Camera Arts

Introduction

This module provides an overview of the camera arts and how they’re used. They include:

- Film photography

- Photography’s impact on traditional media

- Issues of Form and Content

- Darkroom Processes

- The Human Element

- Color Images *Photojournalism

- Modern Developments

- Digital photography

- Time-based mediums:

- Motion pictures

- Video

- Digital streaming images.

- Motion pictures

The invention of the camera and its ability to capture an image with light became the first “high tech” artistic medium of the Industrial Age. Developed during the middle of the nineteenth century, the photographic process changed forever our physical perception of the world and created an uneasy but important relationship between the photograph and other more traditional artistic media.

Early Development

The first attempts to capture an image were made from a camera obscuraused since the 16th century. The device consists of a box or small room with a small hole in one side that acts as a lens. Light from an external scene passes through the hole and strikes the opposite surface inside where it is reproduced upside-down, but with color and perspective preserved. The image is usually projected onto paper adhered to the opposite wall, and can then be traced to produce a highly accurate representation. Experiments in capturing images on film had been conducted in Europe since the late 18th century. Using the camera obscura as a guide, early photographers found ways to chemically fix the projected images onto plates coated with light sensitive materials.

Moreover, they installed glass lenses in their early cameras and experimented with different exposure times for their images. View from the Window at Le Gras is one of the oldest existing photographs, taken in 1826 by French inventor Joseph Niepceusing a process he called heliograpy(“helio” meaning sun and “graph” meaning write). The exposure for the image took eight hours, resulting in the sun casting its light on both sides of the houses in the picture.

Further developments resulted in apertures -- thin circular devices that are calibrated to allow a certain amount of light onto the exposed film (see the examples below). A wide aperture is used for low light conditions, while a smaller aperture is best for bright conditions. Apertures allowed photographers better control over their exposure times. [image]1. Large aperture. 2. Small aperture. The image above is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License (HTML). It is attributed to Dicklyon and the original version can be found here (HTML).

During the 1830’s, Louis Daguerre, having worked with Niepce earlier, developed a more reliable process to capture images on film by using a polished copper plate treated with silver. He termed the images made by this process “Daguerreotypes”. They were sharper in focus and the exposure times were shorter. His photograph Boulevard du Temp from 1838 is taken from his studio window overlooking a busy Paris street. Still, with an exposure of ten minutes, none of the moving traffic or pedestrians stayed still long enough to be recorded. The only person in the image is a man on the lower left, standing at the corner getting his shoes shined.[insert image]Louis Daguerre, Boulevard du Temps, 1838. This image is in the public domain.

At the same time in England, William Henry Fox Talbot was experimenting with other photographic processes. He was creating photogenic drawings by simply placing objects (mostly botanical specimens) over light sensitive paper or plates, then exposing them to the sun. By 1844, he had invented the calotype; a photographic print made from a negativeimage. In contrast, Daguerreotypes were single, positive images that could not be reproduced. Talbot’s calotypes allowed for multiple prints from one negative, setting the standard for the new medium. “Latticed Window at Lacock Abbey” is a print made from the oldest photographic negative in existence.[image]William Henry Fox Talbot, Latticed Window at Lacock Abbey, 1835. Photographic print. National Museum of Photography, Film and Television collection, England. This image is in the public domain.

Impact on other Media

The advent of photography caused a realignment in the use of other two-dimensional media. The photograph was now in direct competition with drawing, painting and printmaking. The camera turns its gaze on the human narrative that stands before it. The photograph gave (for the most part), a realistic and unedited view of our world. It offered a more “true” image of nature because it’s manifest in light, not by the subjective hand and mind of the artist in their studio, which, depending on the style used, is open to manipulation. Its use as a tool for documentation was immediate, which gave the photo a scientific role to play.

Talbot’s photogenic drawings of plant species became detailed documents for study, and the “freeze frame” photos of Eadweard Muybridge helped to understand human and animal movement. But the relative immediacy and improved clarity of the photographic image quickly pitted the camera against painting in the genre of portraiture. Before photography, painted portraits were afforded only to the wealthy and most prominent members of society. They became symbols of social class distinctions. Now portraits became available to individuals and families from all social levels.

Let’s look at two examples from the different mediums to compare and contrast. Gilbert Stuart’s painted portrait of Mrs. Oliver Brewster (Catherine Jones) (1815) not only records the sitter’s identity but also a psychological essence. There is a degree of informality in the work, as she leans forward in the chair, a shawl draped over one shoulder, hands clasped, with raised eyebrows and a slight smile on her lips. Her amusement is palpable and endearing. In the photographic portrait of the English actress Ellen Terry, Julia Margaret Cameron captures the same informality and psychological complexities as Gilbert does, except this time the sitter leans against a patterned background, a simple white gown slips off her shoulders as she gently grasps a necklace with her right hand. Here the sitter’s gaze is cast downward, unsmiling, in a moment of reflection or sadness. The lighting, coming from the right, is used to dramatic effect as it illuminates the left side of Terry’s body but casts the right side in shadow. [image]Julia Margaret Cameron, Portrait of Ellen Terry, 1864. Carbon print. The Royal Photographic Society, United Kingdom. This image is in the public domain.One obvious difference is the lack of color in Cameron’s photo. Her use of black and white creates a graphic composition based on both dramatic and subtle changes in value.

The first color photographs were developed as early as the 1860’s, but these early processes were impractical and of little value. Painters worried that this new medium would spell the end to theirs. In reality, early photographers were influenced by popular styles of painting in creating their own compositions. Cameron’s staged photograph "Queen Esther before King Ahasuerus" from 1865 mimics the Symbolist paintings of the time in both style and subject matter. They used mythology, dramatic poses and other Romantic themes to create visual worlds with dream like figures and dark emotions. You can see the similarity between Cameron’s photograph and George Frederic Watts’ painting “Paolo and Francesca” from about the same time. [image]George Frederic Watts, Paolo and Francesca, c. 1865. Oil on canvas. This image is in the public domain.

It didn’t take long for photographers to see the aesthetic value in the new medium. As early as 1844, Henry Talbot was taking pictures with a concern towards formal composition. The Open Door uses mundane subject matter to create a study in contrasts, visual balance and textures. The solid composition, anchored by the dark rectangle of the door and interior space book ended by sunlit areas, becomes animated with diagonals created in the heavy shadow cast on the door. The broom’s placement and its shadow reinforce this. Vines cropped on each side of the photo’s frame give balance, and the broom straw, stone work and door hardware create visual textures that enhance the effect. Finally, the lamp hanging near the right edge of the frame creates an accent that draws our eye. Early photographs were made from single plates of metal, glass or paper, each one painstakingly prepared, exposed and developed.

In 1884, George Eastman invented transparent roll film; strips of celluloid coated with a light-sensitive emulsion. Four years later, he developed the first hand held camera loaded with roll film. The combination brought access to photography within the reach of almost anyone. Additional advances were made in lens optics and shutter mechanics. By the turn of the nineteenth century, the photograph represented not only a new artistic medium but also a record -- and a symbol -- of the Industrial age itself.

Form and Content

The darkroom became the studio of the photographer. It was there where visual ideas translated into images: an opportunity to manipulate the film negative, to explore techniques and discover the potential the photograph had in interpreting objects and ideas. Alfred Stieglitz understood this potential, and as a photographer, editor and gallery owner, was a major force in promoting photography as an art form. He led in forming the Photo Secession in 1902, a group of photographers who were interested in defining the photograph as an art form in itself, not just by the subject matter in front of the lens. Subject matter became a vehicle for an emphasis on composition, lighting and textural effects. His own photographs reflect a range of themes. The Terminal (1892) is an example of “straight photography”: images from the everyday taken with smaller cameras and little manipulation. In The Terminal, Stieglitz captures a moment of bustling city street life on a cold winter day. A massive stone façade looms in the background while a half-circle of horses and street wagons are led out of the picture to the right. The whole cold, gritty scene is softened by steam rising off the horses and the snow provides highlights. But the photo holds more than formal aesthetic value. The jumble of buildings, machines, humans, animals and weather conditions provides a glimpse into American urban culture straddling two centuries. Within ten years from the time this photo was taken, horses will be replaced by automobiles and subway stations will transform a large city’s movement into the twentieth century. Other photographs by Stieglitz concentrate on more conceptual ideas.

His series of cloud photos, called Equivalents, are efforts to record the essence of a particular reality, and to do it “so completely, that all who see [the picture of it] will relive an equivalent of what has been expressed”. His Equivalents photos establish a new level for the aesthetic content of ideas, and are essentially the first abstract photographs.

Darkroom Processes

The camera’s ability to capture a moment in time is not without difficulties. We’ve all had the experience where we declare “If I only had a camera with me!” On one hand, photographs taken in the studio are controlled productions, with the photographer working to find balances with lighting and composition. On the other hand, straight outdoor photography is unpredictable. Lighting and weather conditions change quickly, and so do the locations where the photographer will find that “one great shot”. To compensate for these variables, photographers typically take hundreds of pictures, bracketing shutter speeds and aperture settings as they go, then carefully editing each negative and print until they find the handful, or perhaps only the one, that will be the best image of them all. The darkroom is where the exposed film is developed. It must be dark to eliminate any chance of outside light ruining the exposed film. In black and white film developing, a low-intensity red or amber colored lamp called a safe lightis used so the photographer can see their way around during developing. The light emitted from the lamp is of a wavelength that does not affect exposure results. [image]Safelight used in the darkroom. The image above is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License (HTML). It is attributed to Douglas Whitaker and the original version can be found here (HTML).

Other tools used in a darkroom are typically an enlarger,an instrument with a lens and aperture in it that projects the image from a negative onto a base. Photographic paperis then placed under the projected image and exposed to light. The paper is put into a series of solutionsthat progressively start and stop the development of the positive photographic image. The development process gives the photographer another opportunity to manipulate the original image. Specific areas on the print can be exposed to more light (“burning” or darkening areas) or less light (“dodging” or lightening areas) in order to bring up details or create more dramatic visual effects. The image can also be cropped from its original size depending on how the photographer wants to present the final image. [image]Photograph of the body of water with dodge and burn text overlaid in order to give an example of the two effects. This image is in the public domain.

Light meters are used to calibrate the amount of light available for a certain exposure. The photographer adjusts the aperture of the camera to allow for more or less light to fall on the film during the initial exposure. But light meters alone don’t guarantee the perfect photograph because they indicate the total amount of light, without respect to specific areas of light or dark within the format of the picture. For this, the photographers Ansel Adams and Fred Archer created the zone system. The system relies on two interrelated factors – the visualizationof how the photographer wants the print to look even before they take it, and a correct light calibration from all the areas by assigning numbers to different brightness values – or ‘zones’ on the value scale, from white to black and all the various gray tones in between. The zone system is tedious both in the field and in the darkroom, but, since its inception in 1940, has spurred creation of photographs absolutely stunning in their clarity, composition and graphic drama. Adams’ Taos Pueblo below is an example. [image]Ansel Adams, Taos Pueblo, 1942. Black and white photograph. Collection of the National Archives, Washington, D.C. This image is in the public domain.

The Human Element

Photography became the most contemporary of artistic media, one particularly suited to record the human dramas being played out in an increasingly modern world. French photographer Robert Doisneau’s The Kiss on the Sidewalk from 1950 shows a romantic kiss as an oasis in the middle of a busy Paris sidewalk. That the photo was not spontaneous but a reenactment takes nothing away from the emotional content: Paris as the city of Love. Eugene Atget (pronounced “Ah-jay”) (1856-1927) was one of the first to use the photograph as a cultural and social document. His images of Paris and its surroundings give poetic witness to the buildings, people and scenes that inhabit and define the city. The work of Diane Arbus (1923-1971) challenges us as we gaze at others who are deviant, marginalized or stand out because of the context in which we see their normality. Arbus’ lens is unflinching in its honesty. She presents images of strangeness and alienation without condescension or judgment. It’s up to us to try to fill in the blanks. Many of the photographs in Robert Frank’s series, The Americans, depicts groups of people in different situations, including riding a bus, watching a rodeo and listening to a speech. His photo essay on American life is seen through the eyes of an observer, not a participant. Instead of voyeuristic, they give a sense of detachment. Only a few of the figures look directly into the camera or directly at other people in the photo. Frank worked hard to maintain the observer’s point of view. Similar to Arbus, the photographs carry overtones of alienation – between the individual and the group. Controversial when first published in the United States in 1959, the book now is seen as one of the most important modern photographic social commentaries.

Color Images

The wider use of color film after 1935 added another dimension to photography. Color can give a stronger sense of reality: the photo looks much like the way we actually see the scene with our eyes. Moreover, the use of color affects the viewer’s perception, triggering memory and reinforcing visual details. Photographers can manipulate color and its effects either before or after the picture is taken. Even though there is no figure present in Grand Canyon, 1973, we observe the landscape through the eyes of the photographer. Joel Meyerowitz makes use of raking light and two sets of complementary colors; orange and blue, yellow and violet giving stark contrast and vibrancy to the photograph. The foreground, bathed in warm light, has details and patterns created by the scrub brush dotting the hill. A bright yellow spike plant rises up out of the desert like a beacon, an exclamation point on a vast, barren landscape. The cool blues and purples in the background soften the plateaus and hills as they disappear on the horizon.

In a final example, the finely meshed screen sporting flies in the foreground dilutes and blurs a warm monochromatic color scheme in Irving Penn’s Summer Sleep(1949). Distortion in the center of the photo takes on a blue hue, visually hovering like a mist over the sleeping figure in the background. For its seemingly informal set up, Penn’s photo is actually a meticulously arranged composition. And the narrative is just as meticulously crafted: serene, gauzy sleep within while trouble waits just beyond.

Photojournalism

The news industry was fundamentally changed with the invention of the photograph. Although pictures were taken of newsworthy stories as early as the 1850’s, the photograph needed to be translated into an engraving before being printed in a newspaper. It wasn’t until the turn of the nineteenth century that newspaper presses could copy original photographs. Photos from around the world showed up on front pages of newspapers defining and illustrating stories, and the world became smaller as this early mass medium gave people access to up to date information…with pictures! Photojournalismis a particular form of journalism that creates images in order to tell a news story and is defined by these three elements:

- Timeliness— the images have meaning in the context of a recently published record of events.

- Objectivity— the situation implied by the images is a fair and accurate representation of the events they depict in both content and tone.

- Narrative— the images combine with other news elements to make facts relatable to the viewer or reader on a cultural level.

As visual information, news images help in shaping our perception of reality and the context surrounding them. [image]Photographs taken by Mathew Brady, Timothy O'Sullivan and others photographers during the American Civil War (below) gave sobering witness to the carnage it produced. Images of soldiers killed in the field help people realize the human toll of war and desensitize their ideas of battle as being particularly heroic. [image]Conf dead chancellorsville edit1. This image is in the public domain. Sometimes soldiers themselves take photographs in the battlefield. In the picture below, Robert F. Sargent, a Chief Photographer’s Mate in the U.S. Coast Guard, gives an eyewitness visual account of Allied troops coming ashore in France on D-Day, 1944. [image]Robert F. Sargent, Landing Craft at Omaha Beach, June 6, 1944. Black and White photograph. United States Coast Guard photo. This image is in the public domain. Photojournalism’s “Golden Age” took place between 1930 and 1950, coinciding with advances in the mediums of radio and television.

Margaret Bourke-White’s photographs helped define the standards of photojournalism. Her work with Life magazine and as the first female war correspondent in Europe produced indelible images of the rise of industry, the effects of the Dust Bowl, the Great Depression and World War Two. Ammonia Storage Tanks (1930) shows masterful composition as she gets four of the massive tanks into the picture. The shadows, industrial grids of metalwork and the inclusion of figures at the top for an indication of scale make a powerful visual statement about the modern industrial landscape. One of her later photographs, A Mile Underground, Kimberly Diamond Mine, South Africa from 1950 frames two black mine workers staring back at the camera lens, their heads high with looks of resigned determination on their faces. Dorothea Lange was employed by the federal government’s Farm Security Administration to document the plight of migrant workers and families dislocated by the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression In America during the 1930’s. Migrant Mother, Nipomo Valley, California is an iconic image of its hardships and the human resolve to survive. Like O’Sullivan’s civil war photos, Lange’s picture puts a face on human tragedy. Photographs like this helped win continued support for president Franklin Roosevelt’s social aid programs. P

Photojournalism does not always find the story in far away places. More often it is in the urban settings of big cities. Weegee (born Arthur Fellig) made a living as a ubiquitous news photographer on the streets of New York City. He documented the sensational, from murders to entertainment, and kept a police radio in his car so as to be the first on the scene of the action. His photo Simply Add Boiling Water from 1937 shows the Hygrade frankfurter building in flames while firemen spray water into it. The photo’s title is ironic and taken from the sign across the center of the building.

Modern Developments

Edwin Land invented the instant camera, capable of taking and developing a photograph, in 1947, followed by the popular SX-70 instant camera in 1972. The SX-70 produced a 3” square-format positive image that developed in front of your eyes. The beauty of instant development for the artist was that during the two or three minutes it took for the image to appear, the film emulsion stayed malleable and able to manipulate. The artist Lucas Samaras used this technique of manipulation to produce some of the most imaginative and visually perplexing images in a series he termed photo-transformations. Using himself as subject, Samaras explores ideas of self-identity, emotional states and the altered reality he creates on film. [image]Polaroid SX-70 Instant Camera. The image above is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License (HTML). It is attributed to Cburnett and the original version can be found here (HTML).

Digital cameras appeared on the market in the mid 1980’s. They allow the capture and storage of images through electronic means (the charge-coupled device) instead of photographic film. This new medium created big advantages over the film camera: the digital camera produces an image instantly, stores many images on a memory card in the camera, and the images can be downloaded to a computer, where they can be further manipulated by editing software and sent anywhere through cyberspace. This eliminated the time and cost involved in film development and created another revolution in the way we access visual information. Digital images start to replace those made with film while still adhering to traditional ideas of design and composition.

The image you see below is a photograph of the Golden Gate Bridge that has been retouched to create light effects traditionally used in paintings. The photograph also uses many of the artistic elements and principles that you learned about in Unit 3 in its composition. [image]Golden Gate Bridge Retouched Terms of Use: The image above is released under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0 (HTML). It is attributed to David Ball and the original version can be found here (HTML). In addition, digital cameras and editing software let artists explore the notion of staged reality: not just recording what they see but creating a new visual reality for the viewer. Sandy Skogland creates and photographs elaborate tableaus inhabited by animals and humans, many times in cornered, theatrical spaces. In a series of images titled True Fiction Two she uses the digital process – and the irony in the title to build fantastically colored, dream like images of decidedly mundane places. By straddling both installation and digital imaging, Skoglund blurs the line between the real and the imagined in art. The photographs of Jeff Wall are similar in content – a blend of the staged and the real, but present themselves in a straightforward style the artist terms as “near documentary”.

Time-based media: Film, Video and Digital With traditional film, what we see as a continuous moving image is actually a linear progression of still photos on a single reel that pass through a lens at a certain rate of speed and are projected onto a screen. We saw a simple form of this process earlier in the pioneering work of Eadweard Muybridge. [image]Eadweard Muybridge, Sequence of a Horse Jumping, 1904. This image is in the public domain. The first motion picture cameras were invented in Europe during the late nineteenth century. These early “movies” lacked a soundtrack and were normally shown along with a live pianist, organ player or orchestra in the theatre to provide the musical accompaniment. In the United States, film went from being a novelty to an art form with D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation in 1915. In it Griffith presents a narrative of the Civil War and its aftermath but with a decidedly racist view of American blacks and the Ku Klux Klan. Film scholars agree, however, that it is the single most important and key film of all time in American movie history - it contains many new cinematic innovations and refinements, technical effects and artistic advancements, including a color sequence at the end. It had a formative influence on future films and has had a recognized impact on film history and the development of film as art. In addition, at almost three hours in length, it was the longest film to date*. *From Filmsite Movie Review: The Birth of a Nation.

Unique to the moving image is its ability to unfold an idea or narrative over time, using the same elements and principles inherent in any artistic medium. Film stills show how dramatic use of lighting, staging and set compositions are embedded throughout an entire film (for formal comparisons, see the work of Cindy Sherman above). Video art, first appearing in the 1960’s and 70’s, uses magnetic tape to record image and sound together. The advantage of video over film is its instant playback and editing capability. One of the pioneers in using video as an art form was Doris Chase. She began by integrating her sculptures with interactive dancers, using special effects to create dreamlike work, and spoke of her ideas in terms of painting with light.

Unlike filmmakers, video artists frequently combine their medium with installation, an art form that uses entire rooms or other specific spaces, to achieve effects beyond mere projection. South Korean video artist Nam June Paik made breakthrough works that comment on culture, technology and politics. Contemporary video artist Bill Viola creates work that is more painterly and physically dramatic, often training the camera on figures within a staged set or spotlighted figures in dark surroundings as they act out emotional gestures and expressions in slow motion. Indeed, his work The Greeting reenacts the emotional embrace seen in the Italian Renaissance painter Jocopo Pontormo’s work The Visitationbelow.[image]Jacopo Pontormo, The Visitation, 1528, oil on canvas. The Church of San Francesco e Michele, Carmignano, Italy. This image is in the public domain. Computers and digital technologyhave, like the camera did over one hundred and fifty years ago, revolutionized the visual art landscape.

Some artists now use digital technology to extend the reach of creative possibilities. Sophisticated software allows any computer user the opportunity to create and manipulate images and information. From still images and animation to streaming digital content and digital installations, computers have become high tech creative tools. In a blending of traditional and new media, artist Chris Finley uses digital templates – software based composition formats – to create his paintings. The work of German artist Jochem Hendricks combines digital technology and human sight. His eye drawings rely on a computer interface to translate the process of looking into physical drawings. Digital technology is a big part of the video and motion picture industries with the capability for high definition images, better editing resources and more areas for exploration to the artist.

Conclusion

The camera arts are relatively new mediums to the world of art but their contributions are perhaps the most significant of all. They are certainly the most complex. Like traditional mediums of drawing, painting and sculpture they allow creative exploration of ideas and the making of objects and images. The difference is in their avenue of expression: by recording images and experiences through light and electronics they, on the one hand, narrow the gap between the worlds of the ‘real’ and the ‘imagined’ and on the other offers us an art form that can invent its own reality with the inclusion of the dimension of time. We watch as a narrative unfolds in front of our eyes. Digital technology has created a whole new kind of spatial dimension: cyberspace.