IND/Economic organisation, sustainability and adaptability

The hunting and gathering economy of Indigenous Australia is based upon principles of reciprocity and use of sustainable land management practices developed over many millennia is home to the oldest living cultures in the world. Over fifty thousand years ago, well before modern people reached America or dominated Europe, people journeyed to the planet’s harshest habitable continent and thrived. New DNA evidence shows Aboriginal Australians were the first modern humans to venture out of Africa. Viewed in the context of world history their achievements are remarkable. To get to Australia from the shores of Asia they made the first open ocean crossing in history. Here they conducted the world’s earliest burials with grave goods, etched the earliest depiction of the human face, engraved the world’s first maps, made the earliest paintings of ceremony and invented unique technologies such as the returning boomerang.

The nature of the resources available within a region largely shaped the socio-economic organisation of the group. For instance, in arid regions of Australia the availability of water determined a higher degree of mobility of Aboriginal groups around their country compared to coastal groups where fresh water was more abundant.

Each nation of people developed a sophisticated stone and wood tool technology drawing on the resources of the area. This was supplemented by trade items received across the trade route system which criss-crossed Aboriginal Australia from the east to the west and from the north to the south.

The Dreaming, all things in one, is the philosophical extension of the practical sustainability that Indigenous people lived by. Resources – foods, materials such as flints, shells, ochres – were carefully managed. This was done through a variety of techniques: providing specific habitats for animals, burning to promote ecologies that favoured certain species of animals and plants, controlling who could access resources at different times. Movement was a necessary part of this management; it allowed the area to recover and reproduce, it allowed Indigenous people to take advantage of resources as they came into season (Keen, 2004, Chapter 4).

The land was the basis for survival, and “many techniques were used to regularise and increase the numbers and growth of plants and animals” (Goodall, 1996, p. 2). Spiritual and kinship relationships determined the distribution of tasks. The health and well being of the land and its people were ensured when the custodians of the land fulfilled their obligations and duties. This included conducting ceremonies and the appropriate use of the land, including regular burning off to cleanse the land and regenerate new growth.

It appeared to the European invaders that Aboriginal people were passive gatherers, in that they did not till the soil, plant crops and reap the produce. These agricultural pursuits were activities which Europeans understood as basic to owning land, because owning land was seen to be tied to making “productive” use of it.

While Indigenous economic life might have been traditionally seen by Europeans as difficult and limited, recent writers have seen hunter-gatherer economies in very different ways. The anthropologist Marshall Sahlins described hunting and gathering societies as the “original affluent societies” because people were not seeking to satisfy endless wants as people do in capitalist systems (1968). This allowed time, as the Australian economist Noel Butlin has described for Indigenous people to allocate “time and resources to all sorts of things, including education and religious life” (Keen, 2004, pp. 4-5). It is also now understood that Indigenous people had time to devote to education and religious life, because food hunting and gathering were entwined with other aspects of life, both social and ceremonial. Dingle suggests that food gathering “was not arduous” but instead food gathering was mixed with “talk and recreation so that work and recreation were intermingled”. Hunting was also “unhurried and intermingled with rest times” (1988, p.12). Indigenous economic life was not “primitive” or “deprived” as non-Indigenous people might have imagined, or still imagine, it to be.

Aboriginal Occupation and Trade Routes

Text adapted from South Australian Government, (2012). ‘Aboriginal Occupation’. Atlas of South Australia.

European Australians have long assumed that Aboriginal people in pre-European times lived in discrete tribes and had little communication with distant groups and minimal interest in technology, trade, money or exchange. This is simply not the case. Aboriginal people were extensive traders, and with various media of exchange or money equivalents, they traded goods over long distances. 'Roads' or trade routes have existed for probably thousands of years, with centres of exchange growing up at key locations long before Europeans arrived.

In fact, it was the existence of these trade centres that attracted the early mission settlements at places like Kopperamanna in the north-east corner of South Australia. Early settlers were sometimes surprised to find that prized items such as steel axes had been introduced long before the arrival of Europeans, having been exchanged for other goods at various centres along the trade routes.

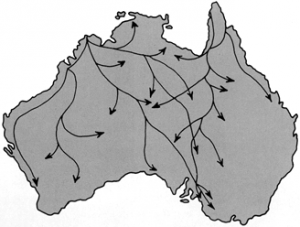

Because of trade on the continent was overland and on foot, the key centres of exchange tended to be well inland at sites where fresh water was plentiful, and access and movement were facilitated along periodic watercourses or between suitably spaced water-holes. These functioning trade centres and been established at sites such as Kopperamanna, Beltana and Ooldea long before Europeans first sighted Australia. Definite patterns of movement were established between these trading centres. Even though particular goods were exchanged across the whole continent, individual people did not travel the whole distance. Rather, goods - and associated stories and ideas - came with traders to a centre, and were exchanged for others. The more valuable items - those that were scarce or found in only a few localities - were traded over very long distances. The rare melo shell, from the east coast of Cape York in Queensland, was traded right down into South Australia, becoming progressively more valuable the further it travelled from its source. A particularly valuable form of ochre was mined at Parachilna on the western edge of the Flinders Ranges. This was traded north, via the exchange centre at Cooper Creek, right into central Queensland. Pituri, the source of a much sought after psycho-active drug, was collected in western Queensland and traded far into South Australia. In return for pituri, ochre from Parachilna found its way to Boolyo (Boulia) in Queensland by way of a number of exchange posts and different carriers. Important ceremonial goods such as pituri and ochre served as currencies in payment for other items.

There is evidence that the trade routes were highly significant in religious-mythological terms and that they followed the 'Dreaming trails' (the routes travelled by ancestral beings) over long distances. While it is no longer possible to study the transfer of pre-European trade items, it is still possible to follow the story-lines of mythological ancestors across many areas. Thus, the route to the Flinders Ranges ochre mines was an emu Dreaming path, used by people who traded with other groups who shared this Dreaming and with whom they held combined ceremonies on their journey. These trade routes illustrate the high degree of interaction between people from different areas, and the extent to which cultural ideas as well as material goods were transferred. The Aboriginal trade map illustrates only some of the trade items which would have been used in pre-European times, and only those routes and exchanges centres for which it was possible to establish detailed knowledge before the people had died out or been displaced by incoming Europeans.

Macassans: Trade routes reaching from China to the North Coast of Australia

Aboriginal people did not only exchange goods and knowledge within and across the Australian continent. From at least the 1700s, fishing fleets from Macassar in Sulewesi (called trepangers) would visit the north coast of Australia in search of sea cucumbers - a highly sought-after delicacy which they then traded to Chinese merchants. Some Aboriginal people joined the Macassans when they returned home, and some even remained in Macassar permanently.