Will it work?

Contents

Consider the purpose

A project that meets an important need for your organisation will contribute towards meeting wider organisational targets. Consider the purpose – what will the project contribute that will further the goals of the organisation? It is often useful to discuss this with the project sponsor and to align the project objectives with the strategic objectives of the organisation. If the ‘fit’ of the project with the organisational direction is considered at an early stage, it might be possible to use the project to address a slightly wider set of concerns and to increase the available resources in recognition of the increased value of the project outcomes. Consider the questions that will help to determine the value of the project to the organisation:

- what is the business case for carrying out this project?

- how exactly will the project contribute to achieving any of the organisation's stated objectives?

If you ask these questions of the project and find that it does not contribute directly, the feasibility of the project should be considered as doubtful because the use of resources will be difficult to justify.

Feasibility studies

For some projects, particularly large or innovative ones, it may be appropriate to carry out a feasibility study before beginning the detailed work of planning and implementation. Alternatively, or in addition, it may be possible or desirable to try out an idea on a small scale, as a pilot project, before the main project begins. It may also be appropriate to carry out a feasibility study when there are still a number of options that would all appear to offer appropriate solutions to the problem addressed by the potential project. A feasibility study can help to clarify which option or options would achieve the objectives in the most acceptable way.

The purpose of a feasibility study is to determine whether the required outputs or outcomes can be achieved with the available resources. It should ensure that the concerns of all the stakeholders are considered. The key issues to be addressed will be:

- Financial – comparing the costs of resourcing the project with the benefits it may bring and the costs that may arise if the project is not implemented.

- Technical – establishing how any new system will mesh with existing systems, fitness for purpose, whether the organisation and staff have competence to work with the new technology, how to manage the transition.

- Environmental and social – stakeholders’ concerns about environmental impact, impact of project on local environment and local social conditions.

- Managerial – examining the implications for work practices, including any need for new staff or training for existing staff, changes to terms and conditions of employment, and implications for equal opportunities.

- Value-related – investigating motivational and cultural issues to make sure that the project will win support, both for the processes used and for the intended outcomes.

A feasibility study may be a relatively brief activity. For a large project, however, it may have to be very comprehensive and could be regarded as a project in its own right, as in Example 1: A feasibility study.

Example 1: A feasibility study

Managers in a public library decided that its members, as well as a wider constituency of citizens in their town, would benefit from a directory of all services relevant to leisure pursuits and informal learning opportunities. The local council indicated that it might assist with publication and supported the idea.

The group conducted a feasibility study to consider whether:

- similar projects have been successful elsewhere in terms of benefits to the local community;

- the proposed project manager, who is a senior librarian, has the time and expertise to manage the project;

- the support required from other agencies in the area for data collection is likely to be forthcoming;

- the time and money are available to complete initial publication and make the directory available to the public;

- statutory agencies or other voluntary organisations will provide funding in the long term to keep the directory up to date.

Risk and contingency planning

Risk in projects may be defined as ‘an event or situation … which can endanger all or part of the project’ (Nickson and Siddons, 1997).

Risk management is fundamental to project management and has an impact on estimates of time and effort required for the project. It is concerned with assessing the kinds of risk associated with trying to make something happen, for example the possibility of delays in the schedule caused through staff sickness or materials not being available at the appropriate time. Risks in a project can be both internal – arising from within the project – and external – arising from the context or environment of the project. Example 2: The potential cost of failing to identify a risk

In the late 1960s, our New York sales office sold a 707 charter to Mr Harold Geneen, then chairman of ITT, for an executive meeting in London. We had 28 of the most senior ITT executives all on one plane, all at the same time. The charter was the first American Airlines flight to London for about 20 years. The ultra-First Class service contained the finest wines, thousands of dollars in gourmet meals, five movies and the best cigars. Our chief pilot was captain, our executive chef from the general office worked the galley, and we had a doctor, nurse, and a security guard onboard. Our New York sales office even sent a senior representative to coordinate all the details. Every detail was taken into consideration, or so we thought.

When we landed at London Gatwick, we taxied to the terminal and our captain asked Ground Control for fuel. We were horrified when a disturbed looking Exxon supervisor came onboard and informed us that because we had forgotten to obtain a credit standing for Exxon in Europe, they would not fuel our plane. In the face of a complete disaster with ITT, our sales rep calmly took out his personal automobile Exxon credit card, studied the back (which contained no credit limit), handed the card to the fuelling supervisor and said, ‘Fill it up.’

Exxon billed the personal card for more than $10,000, and our representative saved the day.

(Kay Muller, Flight Attendant Dallas/Fort Worth in Capozzi, 1998)

Risk in a project is generally limited to the possibility of different hazards impacting on the project, not risk in any form in which it might affect the organisation in which the project is located. There are four stages to risk management:

- identifying the risk – determining which risks are likely to affect the project and documenting the characteristics of each;

- impact assessment – evaluating the risk to assess the range of possible outcomes in relation to the project and the potential impact of each of these;

- developing plans to have in reserve to reduce the impact of the most likely risks and to ensure that these plans are implemented when necessary;

- ensuring that the risks are kept under review and that appropriate plans are developed to meet any changes in the type or likelihood of adverse impact.

Contingency plans indicate what to do if unplanned events occur. They can be as simple as formalising and recording the thought processes when you ask ‘what if …?’ and decide which options you would follow if the ‘what if?’ situation happened. The key points in contingency planning can be summaried as follows:

- Note where extra resources might be obtained in an emergency and be aware of the points in your plan where this might be required.

- Identify in advance those dates, which if missed, will seriously affect your plans, e.g. gaining financial approval from a committee that meets only once every six weeks.

- Know your own plan very well; probe for its weak points and identify those places where there is some ‘slack’ which only you know about …

- Keep all those involved (including yourself) well informed and up-to-date on progress so that problems can be addressed before they cause too much disruption.

- Recognise the key points in your plan where there are alternative courses of action and think through the possible scenarios for each one.

- Learn from experience – sometimes the unpredictable peaks and troughs in activity follow a pattern – it's just that we have yet to recognise it.

The following suggestions for dealing with contingencies were all made by practising managers:

- Break key tasks down to a greater level of detail to give better control.

- Be prepared to overlap phases and tasks in your plan in order to meet time-scales, but give the necessary extra commitment to communication and co-ordination this will require.

- Spend time at the start in order to pre-empt many of the problems.

- Learn from experience, e.g. develop a list of reliable contractors, consultants, etc.

- Try and leave some slack before and after things which you cannot directly control, to minimise the knock-on effect of any problems prior to, or during, such tasks.

- Pull tasks forwards if possible: one less thing to worry about!

In many projects, these four stages are considered almost simultaneously, but in large-scale projects each stage might warrant considerable attention. The main categories of risk can be summarised as:

- physical – loss of, or damage to, information, equipment or buildings as a result of an accident, fire or natural disaster

- technical – systems that do not work or do not work well enough to deliver the anticipated benefits

- labour – key people unable to contribute to the project because of, for example, illness, career change or industrial action

- political/social – for example, withdrawal of support for the project as a result of change of government, a policy change by senior management, or protests from the community, the media, patients, service users or staff

- liability – legal action or the threat of it because some aspect of the project is considered to be illegal or because there may be compensation claims if something goes wrong.

Where a risk can be anticipated, contingency plans can be implemented if the risk materialises, thus reducing its impact. Contingency planning can generate a range of possible responses to potential crisis situations. For example, you may prepare a list of temporary staff or agencies that you can call on in the event of a major flu epidemic among staff. Planning for risk at an early stage also means that the identified risks can be shared with stakeholders when plans are approved and potential costs can be built into the budget.

Risk assessment and impact analysis

Risk assessment involves measuring the probability that a risk will become a reality; impact analysis involves measuring the sensitivity of the project to each identified risk. The key questions are:

- What is the risk – how will I recognise it if it becomes a reality?

- What is the probability of it happening – high, medium or low?

- How serious a threat does it pose to the project – high, medium or low?

- What are the signals or triggers that we should be looking out for?

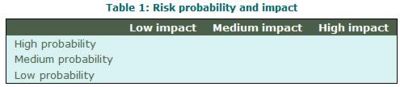

A risk assessed as highly likely to happen and as having a high impact on the project will obviously need closer attention than a risk that is low in terms of both probability and impact. Each risk can be allocated to one of the cells in Table 1 – risk probability and impact.

The top right-hand box is the most dangerous area. If you place a risk statement in this box, you think it is very likely to happen, or you are very uncertain about it, and the consequences for your project would be very severe. Risks that fall into the bottom right-hand box may seem unlikely to happen but you are judging that the effect if they do makes them a danger area for the project.

Strategies for dealing with risks in project management include:

- risk avoidance – for example, where costs outweigh benefits, you may decide to refuse a contract;

- risk reduction – for example, regular reviews can reduce the likelihood of an end-product being unacceptable;

- risk protection – for example, taking out insurance against particular eventualities;

- risk management – for example, making use of written agreements in areas of potential disagreement;

- risk transfer – passing the responsibility for a difficult task within a project to another organisation with more experience in that field.

A risk log should be started for the project at an early stage. This is a list of all the identified risks, together with an assessment of their probability and impact, and contingency plans for dealing with them should they become a reality. A risk log – or risk register – will look something like Table 2 – format for a risk register. It provides a framework for necessary actions to be taken and decisions to be made, and should be amended and added to on a regular basis as the project proceeds.