LESSONS LEARNED FROM ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENTS: A LOOK AT TWO WIDELY DIFFERENT APPROACHES – USA AND THAILAND.

This is an unpublished article I wrote comparing the environment impact assessment processes in Thailand and the United States.

Note: This article was written in 2007 with some sections updated in early 2009, so some specific details may be out of date.

Contents

INTRODUCTION

The concept of assessing the impact on the environment from projects was first put into law in 1969 with National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) in the United States. Since then many countries have implemented similar legislation.

Before the actual assessment of the environmental impact is done, some issues must be addressed. This includes such questions as does an assessment need to be done, what will be the scope of that assessment, and how will alternatives to the project be considered. Other issues also exist around the assessment process including public input.

Different countries differ in their approach to the environment impact assessment. This paper compares environmental impact assessment in two countries - the United States and Thailand. These two countries differ in a number of areas, and a comparison of the two can be instructive in what works and what does not. Other countries are also compared where it may be relevant.

This article concentrates on Thailand and the US for two reasons. First, the author's own experience is in these two countries. Secondly, in many aspects the two countries are near the opposite ends of the spectrum of possibilities.

A note on terminology is necessary. In common usage the term environmental impact assessment (EIA) often can refer to both the process of assessing environmental impact and the document produced as a result of this process. In US law and regulations the document is called an environmental impact statement (EIS), and an environmental impact assessment is the process. In other countries (including Thailand) the term is used in both its meanings. For clarity, we will use EIS for the document and EIA for the process.

This article looks at the legal and regulatory processes involved in environmental impact assessment. The emphasis is on the differences between the two countries. It does not cover the direct assessment methods (such as surveys, computer models, or wildlife assessments) or the actual content of the EIS, except where this reflects those processes. These are based on science and social science principles and essentially the same in most countries. Lastly, post-EIA monitoring as not been included.

It should be noted that we will only briefly looked at legal disputes, as the political situation in Thailand has been changing rapidly in the last few years. This has changed the role of the judiciary and of quasi-judicial bodies (such as National Counter-Corruption Commission).

OVERVIEW OF PROCESS

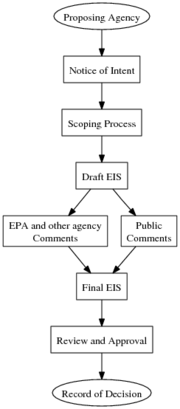

A brief description of the EIA process in both countries is necessary to understand the differences in their approaches. Flowcharts of the processes are shown in Figures 1 and 2. In the United States (Figure 1) the process starts with a notice of intent, which must be published in the Federal Register (the official US government publication). Then comes the scoping process (see below). After scoping the draft EIS is prepared and then released for comment by the public, US Environmental Protection Agency, and any other agencies. The final EIS is then produced after which there can be additional review. Then a record of decision must be published (again in the Federal Register).

It is possible in the US that if an agency feels there is little or no significant environmental impact, it can produce an “environmental assessment” (EA) leading to a “finding of no significant impact” (FONSI). However, these can result in environmental agencies or the public not having any input into the process.

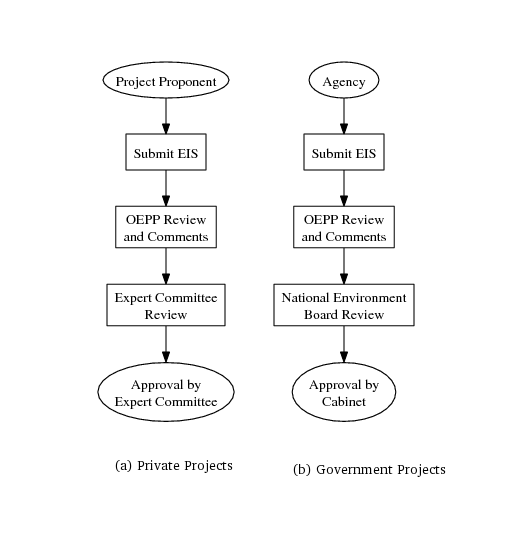

In Thailand there are two processes depending on whether the project is public or private. If the project is private (Figure 2a) then the proponent submits the EIS to the government, which then sends it to a committee of experts who review and approve (or reject) the proposal. For public projects (Figure 2b) the state agency prepares the EIA which then goes to the National Environment Board (headed by the Prime Minister) for review and is then sent to the Cabinet for approval.

PROJECTS COVERED

In the US federal legislation and other “Major Federal Actions” significantly affecting the environment are required to have an environmental impact assessment (NEPA 1969, section 102). This includes actions approved by permit or other means by the federal government. Note that this law does not cover legislation or actions by a state, except where they are federally funded and the federal government exercises control over those funds. More importantly, it does not cover private actions that are licensed solely by a state. Since states do most of the licensing or permitting most private actions are not covered by EIS’s unless they affect a natural park or other federal lands, or involve a federal prerogative, such as nuclear power plants. However, 17 states have there own EIA laws.

In the US only a small percentage of projects actually require an EIS. In most other countries the EIA process covers private processes. This is a major shortcoming of the US EIA process. The net really must extend to all projects which affect the environment in order to have a comprehensive assessment of the impacts of human activities.

It is important to note that the Bush administration has proposed changes to reduce the projects covered by NEPA and ‘streamline‘ the EIA process (Council on Environmental Quality 2003).

In Thailand all projects which are of a type or size specified on a list drawn up by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment are required to go through the EIA process. Two notable items are missing from the list. One is highways. Highways are required to need an EIS only if they go through a wildlife area. The other is that chemical facilities are only required an EIS in three cases - pesticides, fertilizers, and chlor-alkali. These are actually a small percentage of Thai chemical plants.

Although a greater percentage of projects require an EIA in Thailand compared with the US, many projects avoid the EIA process (For example, see Nation 2001). There has been many attempts to circumvent the EIA process by coming up with various ways to describe a project to avoid having to do an assessment.

It is interesting to note that this method of using a list for specification is part of the European Union’s (EU) directive on EIA’s. This directive is mandatory for all EU countries; however, countries are allowed to go further then the directive requires. The directive has two annexes that determine which projects have to have an EIA. Those projects listed in Annex 1 must have an EIA. For those listed in Annex 2 it is up to the individual countries to determine if a project is subject to assessment (European Economic Community 1985). Note that some countries, such as Denmark, adopt the entire list of projects in Annex 2 (Staerdahl et al. 2003).

A major difference between the European system and the Thai system is that in Europe the EIA process has been integrated into the planning and permit processes so it is harder to avoid doing the EIA.

SCOPING

The dictionary definition of scope is “range or extent of action, inquiry, etc.” (Webster’s 1988). The US EIA regulations define scope as consisting of “the range of actions, alternatives, and impacts to be considered in an environmental impact statement”. The regulations further state “There shall be an early and open process for determining the scope of issues to be addressed and for identifying the significant issues related to the proposed action” (Council on Environmental Quality 2002, emphasis added). The agency must publish a notice of intent in the Federal Register before beginning the scoping process.

The scoping process includes: (1) Inviting the participation by federal, state, and local agencies, Indian tribes, the proponent of the action, and other interested persons including those “who might not be in accord with the action”; (2) Determining the significant issues for analysis; (3) Identifying other EIS, environmental reviews, or other analysis already done or under way which may be related to the impact assessment; (4) Indicating the relationship between timing of the EIA and the agency’s planning and decision making.

As the above paragraphs show, scoping in the US is considered an important and integral part of the environmental impact assessment. It sets the playing field in which the EIA is done and provides for early involvement of the stakeholders. In contrast there is no requirement for a scoping process in Thailand. In fact scoping is rarely, if ever, done. This makes the EIA a closed process between the company or agency proposing a project and the consulting company doing the EIA.

For example, the government recently proposed a new elevated road over the Gulf of Thailand. A couple of days later they announced that an EIS had already been completed (Nation 2003a). This was a complete surprise to Thais who had never heard of the plan before. In other countries the scoping process varies considerably; the processes in Thailand and the US are basically the two extremes in scoping. For other examples, see Staerdahl et al. 2003.

ALTERNATIVES

In the US the discussion between the various alternatives is the critical part of the assessment. The EIS requires the section “Alternatives”. The regulations state, “This section is the heart of the environmental impact statement.” (Council on Environmental Quality 2002). The alternatives section includes mitigation measures.

All alternatives must be addressed. This must include the alternative of doing nothing. This is called the “no action” alternative. One alternative is designated the preferred alternative. Omitting an alternative is probably the top reason cited for legal action.

In Thailand, the regulations state, “there should be consideration for alternative ways to develop project” (Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning 2004). However, in practice the author knows of no EIA where this was done, per se. It is often considered as part of a “feasibility study” done before the EIA proper. Even though this feasibility study may be referenced in the EIA, it is often not publicly available and is not subject to the review process. Furthermore, the feasibility study often does not address environmental issues.

An example is the recent natural gas pipeline from Malaysia. It was reported in the media that the selected route was one of seven studied by the investors before they selected it (Nation 2002). Therefore, investors, presumably on economic grounds, rejected the others, not the EIA process. Ironically, the prime minister suggested (after the EIS was produced) using another route which was in the original seven. If that were done a new EIS would be needed!

In the US the stated purpose for requiring the listing of alternatives is to allow reviewers to evaluate the comparative merits of the alternatives (Council on Environmental Quality 2002). In Thailand, by omitting the inclusion of alternatives, an important step is taken out of (1) the public domain and (2) environmental considerations.

PUBLIC REVIEW

It is generally agreed that the role of the public in the EIA process is very important. This is especially true today with the emphasis on stakeholders.

In the US after the completion of the draft EIS comments from the public (and others affected by the action) must be solicited. The regulations require that EPA publish a notice in the Federal Register and no decisions can be made until after at least 90 days. Also all comments must be responded to by either changing the EIS or stating why no change was done. These responses must be stated in the final EIS (Council on Environmental Quality 2002).

In Thailand public participation is in theory part of the system of government. There are guarantees in the constitution, a freedom of information act, and clauses in the environmental legislation. However, there are many limitations to these laws, both legally and in practice. Previous to the new constitution1, constitutional provisions had to be enacted by national laws passed by parliament. Within laws and regulations often the public right to information is subject to the discretion of the government officials in charge (Tan 1998).

Many authors have commented on the lack of public participation in Thailand on environmental issues and the EIA process in particular (for example, see Tan 1998, Staerdahl et al. 2003). There is no provision in the EIA regulations for public participation. The draft EIA does not have to be released to the public, public comments are not asked for, and, critically, the government does not have to respond to public concerns. Usually after the EIA is given to the government for review, the public is not given access to it. Public hearings are seldom held.

In should be noted that public hearings in the two countries are different. In the US, public hearings are basically an open forum for the public to make comments. The date and location of the hearing must be announced within a specified period of time. In 1Approved by referendum in August 2007 Thailand, the hearings are used as a forum for the government/company to justify their project to the public. Commonly used ploys are to change the time or location at the last minute and for the chairman to abruptly end the hearing when too many questions are asked.

A good example of what problems can arise from lack of public participation is the Pak Mun Dam in Northeast Thailand. This dam was proposed and an EIS conducted in 1981. The design and location was modified and not built until 1994. No new EIS was issued. The original EIS was done without any public input and was not released to the public until 10 years later. As stated in a World Commission on Dams (WCD) report on the project, “Affected villagers were not consulted at the early stages of the decision-making process and there were no attempts to include them in the decision making on the project or the mitigation measures” (Amornsakchai et al. 2000). Protests were held by villagers affected both at the dam site and in Bangkok. Again as given by WCD, “Exclusion of affected people from the decision-making process gave rise to protracted protests, demonstrations and confrontations.”

ACTIONS BEFORE EIA IS COMPLETE

In Thailand private projects have to be approved by a board of experts. However, public projects (or more correctly those needing cabinet approval) the EIA is reviewed by the National Environment Board (chaired by the prime minister) and then approved by the cabinet. This has led to the situation where the cabinet approves a project before it is finalized. Since it is the cabinet which is responsible there is little recourse.

The author’s own experience is with the recently opened, new national airport. As we were completing the EIS (all the field work had be completed) we received word that the cabinet had just approved the project. No public input of any type was ever done during the EIA stage.

Another example is a nuclear research reactor in which the EIS was not completed. The director of the national nuclear authority after approving the project stated, “the project is still in the early stages so adjustments [to the EIS] can be made while construction is underway” (Nation 2003b).

It is interesting to note that this is specifically prohibited in the US regulations. “Until an agency issues a record of decision [after the EIA process]…, no action concerning the proposal shall be taken” (Council on Environmental Quality 2002).

WHO DOES THE EIA?

In the US the federal agency responsible for the project is called the lead agency. Usually the lead agency does most of the EIS itself, using other agencies help where they have more expertise. Contractors are seldom used. Where they are used they must submit a disclosure statement specifying that they have no financial or other interest in the outcome of the project.

However, it is the lead agency who also approves the project so a conflict of interest can occur. Also some of the federal agency leaders have often been close to the industries they regulate (especially with mining and petroleum). This is especially true with the Bush administration (Reuters 2002).

In Thailand almost all EIA’s are written by private consulting companies hired by the project’s proponents. Since the consultants are paid by the proponent, they will try to justify a project rather than give an objective assessment of damage. This is especially true in the use of mitigation. If the proponent wishes to apply a specific measure then that will be so.

LEGAL DISPUTES

There is a major difference in the approach to legal challenges to EIS’s. In the US there has been a long history of court challenges to EIS’s. Therefore, a large amount of case law has been developed.

On the other hand in Thailand there has been very few court challenges to EIS’s. This is due to three reasons. First, is simply that the Thai law and regulations are relatively new when compared to the US. Secondly, is the difference in the legal system. The US has a common law system where as Thailand has a code law system, which reduces the importance of case law. Finally, there is a cultural difference. Thais prefer a non-confrontational approach and non-litigious settlements (Tan 1998).

Recently an Administrative Court has been set up in Thailand to handle disputes, but it is too early to make any conclusions concerning it.

CONCLUSION

The types of projects covered by a EIA process must be as wide of a field as possible and include both public and private projects. A list method for determining which projects are covered seems to be the most appropriate method, but the list needs to be exhaustive enough to cover all potential environmental impacts.

In all countries, there is a want to avoid the EIA procedure. Often the agencies/companies overseeing a project try to argue that the project is not required to need the EIS. Other tactics include simply ignoring the law, describing a project in such a way that it is not covered in the law, getting government approval before completing the EIS, and approving an EIS without sufficient input from either the public or academics. Increased enforcement and public participation, and having well written laws and regulations are the best ways of preventing avoidance.

Scoping is a vital part of the EIA process. It sets the playing field on which the impact assessment is done. It identifies the issues involved before the assessment is started, which makes sure the important issues are addressed adequately, while reducing the discussion of irrelevant topics. Most importantly it involves the public and other stakeholders early in the process.

Alternatives must be included as part of the EIA process, not at a pre-EIA stage. Otherwise the effectiveness of the EIA is decreased. The alternatives must be discussed publicly, consider environmental issues, and be compared to a baseline (usually the ‘no action‘ alternative).

Public participation in the process is crucial. Without the public being involved there is too much of a tendency to hide things, which can ultimately lead to corruption. Keeping the EIS (or related documents) secret completely defeats the purpose of an EIA. This can especially be a problem where people are directly affected (for example, relocation due to a dam). Violent protest have been known to happen in such cases. In short, public participation improves the EIA process.

Enforcement of the EIA requirements is a must. Having an independent body required to approve a project’s EIS helps reduce the conflicts of interest that occur when the proponent and the approval agency are the same. The review agency should have enough authority so that it cannot be overridden and therefore the law bypassed. There also needs to be a method of dispute resolution - whether this be the courts, mediation, or other conflict resolution methods.

The EIA process is an important part of environmental legislation in any country. But it is only as good as the laws, regulations, and practices which are written and applied.

REFERENCES

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969, 1969. Title 42 United States Code, Sections 4321-4347.

Webster’s New World Dictionary, 1988. Simon and Schuster, New York, USA.

S. Amornsakchai, P. Annez, S. Vongvisessomjai, S. Choowaew, P. Kunurat, J. Nippanon, R. Schouten, P. Sripapatrprasite, C. Vaddhanaphuti, C. Vidthayanon, W. Wirojanagud, and E. Wattana. Pak Mun Dam, Mekong River Basin, Thailand. A WCD Case Study Prepared as an Input to the World Commission on Dams. World Commission on Dams, 2000.

Council on Environmental Quality. Code of Federal Regulations. Government Printing Office, 2002. Title 40, Chapter 5, Part 1500.

Council on Environmental Quality. Modernizing NEPA Implementation. The NEPA Task Force Report to the Council on Environmental Quality, 2003.

Davis, Wendy B., The Fox is Guarding the Henhouse: Enhancing the Role of the EPA in FONSI Determinations Pursuant to NEPA, Akron Law Review, 39(35):35 – 72, 2006.

European Economic Community. Council Directive of 27 June 1985, 1985.

The Nation, Villagers Raise Red Flags in Klong Dan, September 13 2001. Bangkok, Thailand.

The Nation, Thaksin Proposes Pipeline Diversion, April 12 2002. Bangkok, Thailand.

The Nation, Seabridge Plan Draws Flak, July 9 2003a. Bangkok, Thailand.

The Nation, Nuclear Chief Defends Surprise Approval, October 30 2003b. Bangkok, Thailand.

Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning. General Guidelines in Preparing EIA Report, Government of Thailand, 2004.

Reuters, Rocky Mountain Methane Opens New US Energy Fight, May 8 2002.

Staerdahl, Jens, Henning Schroll, Zuriati Zakaria, Maimon Abdullah, Neil Dewar, and Noppaporn Panich. Environmental Impact Assessment in Thailand, Malaysia and Denmark, 2003.

Tan, Alan K. J., Preliminary Assessment of Thailand’s Environmental Law. Technical report, Asia-Pacific Centre for Environmental Law, 1998.