User:Fordn/Books/Principles and practices of online teaching

Contents

- 1 Course information

- 2 Contexts for teaching & learning

- 3 Activities for online learning

- 4 Resources for online learning

- 4.1 Resources and learning content

- 4.2 Reflect

- 4.3 What are open education resources?

- 4.4 Why use OERs?

- 4.5 The Creative Commons license

- 4.6 Some OER repositories

- 4.7 Reflect

- 4.8 Creating your own resources

- 4.9 Make your own media

- 4.10 Share some of your own

- 4.11 Images and icons

- 4.12 Images

- 4.13 Discuss

- 5 Supporting online learning

- 6 Pedagogy and technology

- 7 Promoting online interaction

- 7.1 The importance of interaction

- 7.2 Reflect

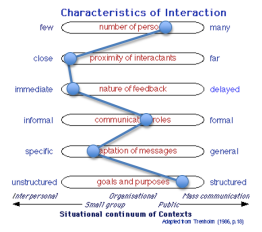

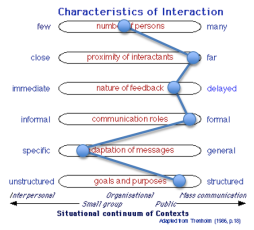

- 7.3 Characteristics of interaction

- 7.4 Implications for online teaching

- 7.5 Promoting online interaction

- 7.6 Types of interaction

- 7.7 Activity

- 7.8 Promoting online interaction: resource-discourse

- 7.9 Promoting online interaction: transactional distance

- 7.10 Synchronous and asynchronous dimensions

- 7.11 Questions are key

- 8 Introduction to Instructional Design

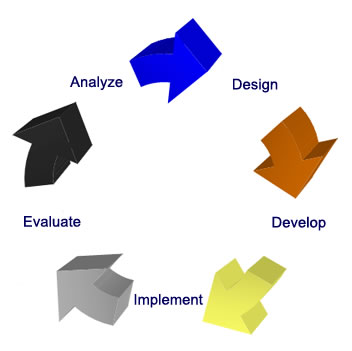

- 8.1 The ADDIE instructional design model

- 8.2 Links to instructional design sites

- 8.3 The importance of interactionThe analysis phase is the starting point for the instructional design process. In this phases the following areas should be addressed: (click on the link)

- 8.4 Conduct Needs Assessment

- 8.5 Define the Characteristics of the Learner

- 8.6 What do you need to know about your learners?

- 8.7 Knowing my learners - some implications

- 8.8 Define the Learning Environment

- 8.9 Define goals and objectives

- 8.10 Objectives vs. Goals (aims)

- 8.11 URLs for Instructional Objectives

- 8.12 Define pedagogical approach(es)

- 8.13 Define introduction, body, and conclusion (using events of instruction)

- 8.14 Define assessment strategy

- 8.15 Development

- 8.16 Reflective Activity

- 8.17 Implementation

- 8.18 Helping Learners Get Benefit from Activities

- 8.19 How Might Learners Make Their Response?

- 8.20 Assessment Strategies

- 8.21 Evaluation

- 8.22 Evaluation Techniques

- 8.23 Reflect

Course information

Code: IQ115

Category: Inquire

Target Audience: All

Availability: 2012

Learning Intentions: The goals of this course focus on preparing participants to become effective online teachers by; exploring the essential skill sets necessary for teaching in an online environment implementing effective practices and strategies for teaching in an online environment. Upon successful completion of this course, you will be able to: Make informed decisions about the appropriate use of online technologies, both synchronous and asynchronous, to support particular pedagogical practices, demonstrate knowledge of the principles of instructional design, and online pedagogy in relation to online teaching and learning. Develop appropriate strategies for promoting active learning. Articulate an instructor’s role in an online learning environment

Pre-requisites: Regular access to the WWW and the ability to create accounts in various online environments is required.

Participants: Teachers at any level of the education system who are currently teaching online or who are planning on doing so in the near future.

Length and provision: This course runs over a ten week period, and uses a combination of synchronous and asynchronous technologies.

Description: The "Principles and Practices of Online Teaching" course is designed for teachers at any level who are involved in working with students in an online environment. Whether you design and deliver courses that are fully or partially run online, the "Principles and Practices of Online Teaching" course will help develop the understandings you need to effectively teach online or blend online segments with your traditional face-to-face courses.

Rationale: The use of online technologies to supplement face to face teaching or to facilitate fully online course provision is increasing in many areas of our education system. To operate effectively in an online environment, teachers will need to learn and embrace a new set of skills and understandings.

Course Content

- Getting started - preparing yourself, your course, and your students for a constructive learning community.

- Contexts for online teaching and learning

- Selecting resources for online learning

- Creating resources for online learning

- Online pedagogies - learning as interaction, learning as inquiry, resource based learning, learning as activity.

- Online technologies - synchronous and asynchronous

- Instructional design - from 'lesson' to 'course'

- Promoting online participation and interaction - (a) making the most of asynchronous forums

- Promoting online participation and interaction - (a) working in the synchronous online environment

- Bringing it all together

The "Principles and Practices of Online Teaching" course is designed for teachers at any level who are involved in working with students in an online environment. Whether you design and deliver courses that are fully or partially run online, the "Principles and Practices of Online Teaching" course will help develop the understandings you need to effectively teach online or blend online segments with your traditional face-to-face courses.

Contexts for teaching & learning

In this module you'll consider the factors that need to be taken into account when considering the context of learners and the learning in the online learning environment. By working through this module you will:

- consider importance of the learner's external and internal environment factors in learning design decisions.

- use a simple model to consider the following variables in terms of the context for online learning:

- formal vs informal learning

- individual vs group learning

- synchronous vs asynchronous learning

- apply your knowledge in a simply task designed to demonstrate your undersandings of these variables.

The focal point of this module is the simple task that has been set, which requires a brief analysis of an online learning experience, and some interaction with other course members about what they have found.

Context

Much is written about context in learning or learning context, and you are fee to explore this at length in your own inquiry in the Web, but for this course we want to focus on a notion of context that includes the following:

- The learner's external environment - i.e physical space, available resources, time available, access to mentoring support etc.

- The learner's internal environment - i.e. existing skills/knowledge, beliefs, thoughts, hopes etc.

- The learning experience - i.e. formal/informal, group/individual, synchronous/asynchronous (see CUBE activity next)

It is important that, when beginning the process of designing and developing an online learning experience that consideration is given to these issues. Just as in a face to face context, the course design decisions you make will need to reflect an understanding of the context of your learners. Otherwise you risk developing a 'one-size-fits-all' experience that may end up excluding some people because it doesn't fit with their time/space/expectations.

Many online course developers adopt some sort of 'pre-assessment' to determine the context of learners before they begin, and then design the experience ot accommodate those needs and expectations. Others try to design the experience to ensure the maximum flexibility and choice to allow learners to plot their own pathway of participation through what is presented.

Establishing the context for teaching and learning is an essential first step in ensuring that all learners involved will have their needs catered for and are able to participate to the extent that they want to or will be required to.

Reflect

Think about your own participation in this course...

- Do you have a clear set of personal goals and expectations of what you want to get from this course? And have you explored the course content to discover a pathway that will ensure these are met?

- What time do you have to devote to study in this course? How will this impact on how you will engage with the various modules, tasks and reflective activities?

- What access do you have to online technologies required to access the course modules and to participate in the synchronous elements of the course? Will this limit your participation in the course in any way? What alternatives can you find if that's the case?

- How important is the 'social' dimension to learning for you? What commitment can you make to participating in the forums? What are your expectations of others contributing to the forums in response to you?

- What set of existing skills, knowledge, beliefs about online teaching do you bring to this course? Are you already teaching online? Have you been an online learner before? How might these experiences shape your participation in this course?

- Do you currently have a context into which you can immediately apply the things you are going to learn in this course? If not, how are you going to make the learning from this course 'authentic'?

Use the contexts for teaching and learning forum to share your thoughts and to learn about the context of others.

Introducing the CUBE

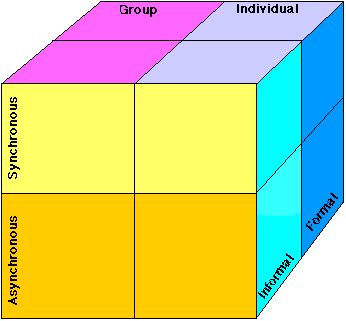

As you may have begun to appreciate, the online environment embraces a wide range of educational contexts, technologies and uses. The diagram below is an attempt to portray the relationship between three sets of variables which may assist you in understanding these differences.

This cube is a simple representation of three dimensions of the teaching and learning process in the Global Classroom. The front face (brown tones) considers the ICT issues, the side face (blue tones) considers the motivation for or purpose of the learning experience, while the top face (pink tones) considers the nature of participation.

What the dimensions mean

Motivation/purpose

- 'formal' distance education provision refers to courses of study or programmes which have been designed to meet particular learning outcomes. These may include courses which lead to qualifications, or programmes operating in a classroom, designed by a teacher for a particular purpose. In a tertiary context this is referred to as a "credentialled" outcome.

- 'informal' distance education refers to the kinds of learning activities undertaken by individuals or groups which are not part of a pre-designed learning programme, or prescribed by someone else. Informal distance learning is usually initiated by the learner for their own purposes, and may include collaborative research, information access, interviews etc. In a tertiary context this is referred to as a "non-credentialled" outcome.

Participation

- 'personal' access to distance education provision occurs when an individual undertakes a programme of learning working independently. Good examples of this occur in what is known as 'self-paced' or 'independent' learning modules, where there are no requirements for interaction or collaboration with others.

- 'group' or 'cohort' access to distance education requires a group or 'cohort' of students to participate in the learning process. Usually, this is characterised by paticipation in collaborative or group interaction which is important to the outcomes of the learning experience. (collaborative research, remote teaching, interviews, group assignments etc.)

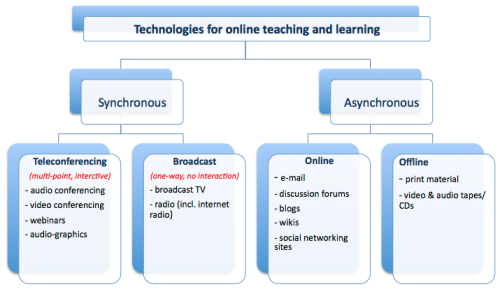

Technology

- 'synchronous' communication - refers to communications that are happening in real time, simultaneous (eg video/audio conferencing, IRC (chat), interactive whiteboards etc.) Learners may be separated by place, but must be available at the same time in order to participate.

- 'asynchronous' communication - refers to communications which are time independent (eg. e-mail, listservs, blogs, WWW, print material) Learners may access learning materials at the time and place they choose.

This cube can be used to "plot" the different types of Global Classroom activity, according to the attributes involved. By considering each of these three dimensions you will be able to identify which quadrant of the cube a particular online course or activity will 'fit'. (NB - often a whole online course may comprise of many activities that will 'fit' in different quadrants of this cube.

The easiest way of doing this may be to consider each pair of criteria being the ends of a 10 point scale. The to think of where abouts on that scale the activity or project you are looking at might be placed. In this way you can get an idea of where the activity 'tends' to be.

NOTE - this is not an exact science - it is merely intended to be used as a means of helping understand the range of contexts and motivations for participation in online learning.

Some examples

- Student at home using skype to communicate with a friend = synchronous/individual/informal, since this is an individual involved in an activity occurring in 'real time', where the purpose is informal, ie not relating specifically to a qualification or 'credit'. Of course, if the student had been communicating using email the mix would be asynchronous/individual/informal

- A class participating in a LEARNZ fieldtrip = asynchronous/group/formal when using the online activities and discussion board, or synchronous/group/fomal when participating in the audio conferences. Of course, if one of the students in the class goes home and browses the site on his/her own through interest the mix might be asynchronous/individual/informal.

The important thing about this analysis is that it emphasises the need for these dimensions to be considered during the design phase of any online learning activity. Later in this course we will cover some of the considerations relating to instructional design, and the need to determine the appropriate match between technology, learner needs and teaching approaches.

Reflect

Can you think of an online course or learning experience that you've been a part of where your experience was limited by the design that excluded your participation for some reason (e.g. requiring synchronous participation at a time that doesn't suit, requiring group work where you wanted to pursue a personal need etc.) . Summarise your experience - identify what the limitations in the design were, and how could they have been addressed?

Apply the cube

Take a moment to think about how the 'cube' can be helpful in terms of understanding the design decisions that underpin different online learning experiences. You may choose one that is familiar to you (or one you may have designed or participated in yourself) and apply the thinking of the cube as follows.

- Briefly describe the online learning experience you are using - what is it called, what is the learning intention, what level is it designed for and provide a URL if available.

- On a scale of 1 - 10 (1 being group and 10 being completely individual/indpendent) where would you position the experience you have chosen in terms of how it is intended to be participated in?

- On a scale of 1 - 10 (1 being formal and 10 being informal) where would you position the experience you have chosen in terms of the recognition/motivation for participating?

- On a scale of 1 - 10 (1 being synchronous and 10 being asynchronous) where would you position the experience you have chosen in terms of the way(s) learners participate?

Share your learning experience and your assessment of it according to the CUBE model in the contexts for teaching and learning forum (NB a forum has been chosen for this activity because it will allow others to read and comment on what you have submitted.)

Some online learning experience examples

Here are some online learning experience examples you could choose from if you don't have anything that comes to mind:

- Connect with Haji Kamal. Can you help a young lieutenant make a good impression on a tribal leader in Afghanistan?

- Weather and climate - from the Atmospheric Science Program, Geography Department, Indiana University

- Global warming simulation. You’re in charge of development decisions in Brazil. The decisions you make speed or slow global warming.

- Similar Triangles - from the Khan Academy, understanding similar triangles

- Study Spanish - a free online course for learning Spanish - students participate in a collaborative task, although not online, this same task could easily be carried out in a video conference or webinar situation for instance.

- Global classroom projects - links to lists of projects for middle primary students

- Water purification - a telecollaborative project for students in grades 9 - 12 studying technologies related to water purification.

- Estimating lengths, areas and angles - taking the guess-work out of estimating

Activities for online learning

Learning activity is the 'meat' in our hamburger metaphor - it is the centrepiece, the main ingredient.

In this module you'll be introduced thinking about learning as activity, and how learning activity should be the focus of what we plan for as teachers in the online environment.

By working through this module you will:

Learn about why activities are important, and how we should prioritise them in our approach to learning design.

Consider how we can design learning activity that promotes higher order thinking.

Explore the types of activities that can be used in an online environment, and consider the advantages of these.

For those with less time to spend on this module we recommend you focus on the topic on types of activities and think about which of these might be useful to incorporate into your online learning experience.

Learning as activity

"What we have to learn to do, we learn by doing" - Aristotle (384 BC - 322 BC)

“We learn by doing and realising what came from what we did” John Dewey (1933)

Pause for a moment and think of a time in your own schooling when you learned something of significance, a unit of work, a particular teacher, a class you were in. I've asked this question dozens of times in workshops and when I ask participants to share what happened, and identify the characteristics of that learning experience one thing emerges overwhelmingly. The common thread in all the responses is usually that the learning was associated with describing an activity - a time when, as a learner, the person was actively engaged in doing something. Only occasionally do things like "a lecture' or 'reading a book' get mentioned.

The way people learn pivots on them engaging and having the right experiences. In the past, the perception was that the teacher was in charge of the learning process but in reality a very good teacher guides and directs rather than telling. What they guide or direct is the activity of learning - the tasks that learners are engaged in. Ask any early childhood educator - they'll provide you with plenty of the theory - and thoughts on practice - to support this.

In the exploration of learning theories in the module on pedagogy and technology you'll discover that one of the characteristics of the currently adopted theories such as constructivism and constructionism for instance is that they are activity based. There is a strong emphasis on learning as a process that is active and participatory, not passive and 'receiving'.

The reason for this emphasis here is that with online learning, there is an danger, inherent in the way the technologies are structured and adopted, as well as being influenced by the physical separation of the teacher and learners, of adopting a more transmissive approach to teaching. While many courses (including this one) will provide information to be read and engaged with, the central focus of any effective teaching/learning event will be the activity - the thing that invites participation and engagement. The information/resources/content should serve to support/inform/guide that activity.

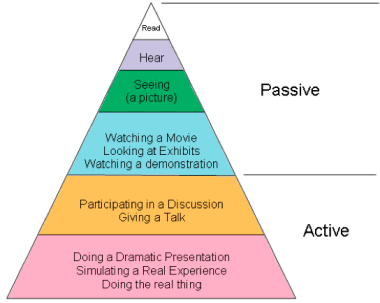

Dale's Cone

Years ago an educator named Edgar Dale, often cited as the father of modern media in education, developed from his experience in teaching and his observations of learners the "cone of experience" (see figure below). The cone is based on the relationships of various educational experiences to reality (real life).

In his original version, Dale calls the bottom level of the cone, "direct purposeful experiences,". This represents reality or the closest things to real, everyday life. Dale's observations and practical experience led him to conclude that the closer a learning experience could be to providing direct, puposeful experince, the better the chance that many students can learn from it. The closer to the top of the cone, the greater the level of abstraction, and the more difficulty students have in retaining what is learned.

There has been a lot written about Dale's cone since it was introduced, included a lot of 'pseudo research' that attempted to apply statistics to the levels, claiming percentages of success in learning at each stage. Much of this has now been de-bunked, but the original work of Dale holds true - that learners are more likely to retain what they learn through direct, purposeful experience, than simply engaging with iconic representations such as text.

As we design online learning experiences, we must hold this thought, and ensure that what we design doesn't simply involve reading lots of text, and hopefully constructing meaning from it in the recesses of our minds. We need to be thinking how we can create the conditions and opportunity for learners to engage in direct, purposeful experiences where-ever possible.

Thinking a little more about Dale's cone helps us make decisions about resources or activities. Consider the following table:

| "layer" | online application |

| Read | Written instructions, online readings, links, downloadable PDFs, texts. |

| Hear | Podcasts, audio files, broadcast (internet) radio, distributed CDs. |

| View image | Inclusion of still images, info-graphics, image libraries. |

| View movie or demonstration |

Embedded movie files, videos of demonstrations or explanations, distributed DVDs. |

| Participate in discussion |

Audio/video conferencing, webinars, online forums and discussion boards. |

| Simulation or dramatic presentation |

Learners record themselves undertaking a dramatic presentation and share online. Use of computer-based simulations. MMOGs etc. |

| Direct, purposeful Experience |

Set tasks that involve field trips, practical experiences etc. in the local context, followed by reflective reports and/or feedback from a local mentor/supervisor. |

Discuss

Learning activity should be the 'meat' in our online learning experience. As teachers and learning designers, we need to avoid the temptation (default position?) to simply use the online environment as a transmissive medium. Our challenge is to consider all the ways we can to actively engage our learners in ways that will increase the likelihood of them retaining what they learn.

- How could you apply the principles of Dale's cone to your online learning experience? Are there more ways that you could plan for to increase the level of learner engagement and decrease the level of abstraction?

- What other online applications can you think of to illustrate the selection of resources and sorts of activities that could be used at each 'level' of Dale's cone above?

Higher order thinking

Higher-order thinking requires students to manipulate information and ideas in ways that transform their meaning and implications. In contrast, Lower-order thinking occurs when students are asked to remember or recite factual information or to employ rules and algorithms through repetitive routines.

We may engage in forms of lower order thinking when providing scaffolded support for learners, to help them to a level where they have the necessary pre-knowledge to engage in higher order thinking activities. The challenge for us as educators is to ensure that in our questioning approach, our setting of tasks and activities, and in the group work we encourage, we are consciously 'raising the bar' for learners, and encouraging higher order thinking.

Some frameworks to guide us

For many educators, Bloom's taxonomy serves as the basis for what are now called Higher Order Thinking skills. Generally the concept is that higher order skills are complex combinations of lower skills. Rather than replicate lots of information about this approach, this slideshow provides a useful summary.

Another framework being used widely now is the SOLO taxonomy (Structure of Observerd Learning Outcomes). It describes level of increasing complexity in a student's understanding of a subject, through five stages, and it is claimed to be applicable to any subject area. Not all students get through all five stages, of course, and indeed not all teaching (and even less "training" is designed to take them all the way). This slideshow (from TKI) provides more information about this approach.

Further reading

HOTS: Higher order thinking - a goldmine of well summarized approaches, strategies and readings for fostering higher order thinking.

HIgher order thinking- a very readable summary of key ideas by Alice Thomas, and Glenda Thorne.

Discuss

Thinking of ways to develop higher order thinking skills among our learners is pretty common place in education now-a-days. This topic is inserted here merely to keep front of mind the importance of considering how we can incorporate activities and challenges in our onlline work with students that foster thinking at this level.

From your own understanding of higher order thinking skills, or from your reading of the material above, share your thoughts in response to the following questions:

- when is it justified to ask questions or set tasks that may be considered lower order thinking in our online courses?

- why do you think that so much of the early online learning course material was criticised for focusing only on lower order thinking, with overuse of simple 'drill and regurgitate' approaches?

- what are the strengths/weaknesses of each of the frameworks outlined above (Blooms and SOLO)? Which might you use to inform the work you are planning for your online learning experience?

Choosing activities

"If you tell me I will forget

If you show me I might remember

But if you involve me, I will learn" —Chinese Proverb

There are plenty of ways in which you can engage learners in activities in an online environment, a range of these are outlined in the following section. There is a danger, however, in making activities seem like 'busy work', rather than contributing significantly to the learning - and indeed, they may be the substantive part of the course.

When you choose types of activities for your online learning experience, consider:

- What knowledge/skills do you want the students to have at the end of the course?

- Do you want to integrate additional collaborative activities, case studies, problem-solving, etc. to involve students in higher level thinking?

- Do you want to simply keep the students busy, or do you want the activities to promote deeper learning?

Types of activity in an online context

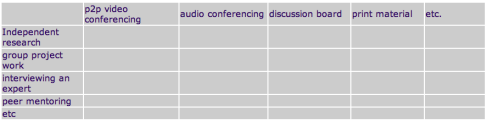

|

Personal

|

Asynchronous online

|

Synchronous online

|

Discuss

There are a plethora of ideas available for creating activities within an online learning context - the important thing is to ensure that they are contributing to the overall goals of the experience, and don't simply become 'busy work'.

Consider the list above and choose just one or two of the activities suggested here. Think about how you might incorporate these into the experience you are designing - more importantly, think about why you would incorporate them. What purpose would they serve in terms of assessment, learner self-assessment, scaffolding learning, peer critique etc.?

Resources for online learning

Resources for learning are one of the three key ingredients in designing a successful online learning experience. Resources represent the content of online learning. Traditional views of content as 'authoritative', and 'quality assured' are being challenged in the online world, with the ease of access to a broad range of resources made possible using a simple search engine. In addition, the tools for creating, managing and distributing resources are now available to allow learners themselves to generate and share resources.

By working through this module you will:

- explore some of the online resource repositories that are available and identify resources that may be useful to you.

- consider the use of open education resources (OERs) and some of the policies and 'rules' around their use.

- look at some of the tools available for creating user generated resources (UGR) and how these might be deployed in your context

- be introduced to the use of images and icons in online courses, and explore some open resource libraries for you to use.

For those with less time to spend on this module we recommend you skim the "Reflection" questions at the end of ech of the topics in this module to check your understanding of what is being covered, and refer back to the relevant module content when working through the module on activities for online learning to help inform decisions there.

Resources and learning content

Learning content has historically formed the centre-piece of most instructional processes. This content has generally been valued because it has been through the publication process and is quality assured, both in terms of the integrity of the information in it and the way it is presented.

In the online world there is a growing array of resources now available - students (and teachers) are no longer restricted to using print-based materials or other traditional sources.

Some of the benefits online resources provide include:

- lowered costs of development, publication and distribution

- multi-media elements are often more engaging and illustrative

- engagement with the content can be more interactive, less passive

- embedded links create multiple learning pathways within the same resource

- accessible 24/7, and by multiple users

- can be re-used within assignments and presentations (assuming the appropriate licensing).

Browse some of the links below to consider examples of the range of types resources and learning content available to you online:

- Electrocity

- Pest world for Kids

- Free rice

- Power-up

- The story of Stuff

- Inanimate Alice

- DebateGraph

- Boolify

Resource repositories

to help make these learning resources more accessible, many countries, organsiations and educational authorities have created repositories where these are stored.

This may not necessarily mean physically storing the resource - that could exist anywhere. A resource repository will more importantly organise and classify the resources, enabling the resources to be searched and sorted, and often have comments added to them by 'experts' or by other teachers that will be helpful in making choices about their use.

Consider the following examples, and think of how helpful these might be in your teaching:

- NZMaths Learning Objects

- Software for learning

- NASA clips

- Khan Academy (video clips)

- Te Kete Ipurangi (TKI)

- 2Learn.ca

- Slideshare

- TeacherTube

- EdNA online

- Chalkface

- Curriculum exchange

For more information and links about resources and resource repositiories that you can access and use for your online teaching check out the link onOpen Education Resources.

Reflect

Resources and learning content form the 'veges' in our burger metaphor. The 'veges' provide the essential information and knowledge required to complete the learning activity.

Of course, what is presented above is only a sample, but provided here to stimulate your thinking and consider the value of pre-prepared online resources in your teaching. Consider:

- How might you use any of these in the online learning episode you are preparing?

- What advantages do they offer over traditional resources?

- What support or scaffolds would you need to put around these resources to ensure they are used in a way that produces the learning outcomes you intend?

- Are there any specific resources ore repositories you've used in the past that would be valuable to share with others on this course?

What are open education resources?

Open educational resources (OER) are digital materials that can be re-used for teaching, learning, research and more, made available for free through open licenses, which allow uses of the materials that would not be easily permitted under copyright alone.[ref: Wikipedia]

The term Open Educational Resources (OER) was first adopted by UNESCO in 2002 and refers to educational materials and resources offered freely and openly for anyone to use and under some licenses, to re-mix, improve and redistribute.

OERs are produced to support learning and teaching and may even be created as part of the learning and teaching processes. Content created by students using the digital tools at their disposal during learning activities could potentially become part of an OER repository (see section on tools for creating resources). This raises considerable questions around ownership and attribution (see section below on creative commons).

OERs became the focus of attention when institutions like MIT started their 'open courseware' intiative, putting lecture notes, exams and videos online and available for free. The Open University followed suit with their 'OpenLearn' initiative, offering over 600 courses online for free. Each of these initiatives demonstrate the realisation that the value of online teaching (indeed, all teaching?) lies not in the transmission of content, but in the quality of the teaching and learning exchange that takes place in and around the content. What you get is simply access to the resources - no suport from teachers or tutors, and no engagement in any form of learning activity. Since the beginning of the open courseware initiative, MIT's enrolments have actually grown in many areas, not decreased.

Why use OERs?

There are a range of reasons why you might consider using OERs in your preparation of online courses (or all your courses for that matter!). Here are some:

- To help reduce or minimise the cost of access to resources to your organisation and/or students,

- Rather than limiting ideas to those approved by a small group of publishers, OERs allow educational communities to pool individual resources from around the world to bring together the best ideas.

- Author participation is encouraged by making it easier to publish and update content, allowing them to share their ideas with the world without navigating the many barriers associated with traditional publication models.

- You can try new ways of teaching and learning, many of which are more collaborative and participatory.

- You have the flexibility to adapt materials for their specific needs (using the appropriate CC license) – making it relevant to teacher and students needs.

- OERs are relevant, usable, adaptable, and free

- You save time, cut costs and contribute to improving the quality of learning in your own classroom and around the world

- Students can be more involved, using the OER process as a way to collaborate with them on content creation.

From the perspective of an online educator, the use of OERs also takes the head-aches out of having to pay licencing fees each time the resource is used in a course. In addition, students are able to take all or part of the appropriately licensed resources and re-use them in their assignment work or generate new content for others to access and use.

The Creative Commons license

Creative Commons is an alternative to the traditional copyright process, and provides a range of copyright licences, freely available to the public, which allow those creating intellectual property – including authors, artists, educators and scientists – to mark their work with the freedoms they want it to carry.

The intent behind the Creative Commons approach is well summed up in the by-line of the Creative Commons organisation which is: "Share, re-use, re-mix - legally".

Professor Lawrence Lessig is one of North America’s leading academics and widely known in the global Internet community as a vocal proponent of reduced legal restrictions on digital copyright, and a champion of notions of ‘fair use’ and ‘free culture’.

Watch this video (recorded at Nethui 2011) Professor Lessig talks to CORE Education's Director of eLearning Derek Wenmoth about creative commons and copyright in the classroom.

The Creative Commons licensing process has now gained such momentum that it has similar legal recognition as the traditional copyright process.

There are six main categories of licence that are recognised internationally, and these can be applied to any content created by the author through a simple process. The New Zealand Creative Commons website has some esy to follow advice on how to choose and apply a CC license if you are interested.

Many schools are now considering implementing a Creative Commons licensing policy to cover materials produced by teachers and students, and to provide guidance regarding the use and re-use of materials accessed from elsewhere.

Some OER repositories

There are an increasing number of OER repositories appearing online - here are just a few of the more established ones, chosen here because they represent different approaches and purposes:

- WikiEducator - a global community resource supported by the Open Education Resource Foundation, an independent non-profit based at Otago Polytechnic for the development of free educational content. The Commonwealth of Learning provides financial support to the OER Foundation.

- 80 OERs for publishing and development initiatives - a list of 80 online resources that you can use to learn how to build or participate in a collaborative educational effort that focuses on publication and development of those materials.

- Khan Academy - Started by Salman Khan in 2006, the website supplies a free online collection of more than 2,400 micro lectures via video tutorials stored on YouTube. The Academy's mission is "providing a high quality education to anyone, anywhere".

- Another site you might find helpful is OER GLue. This one isn't a repository as such, but a clever online application that allows you to gather a set of OERs together, add activities to them and then present them as a course (kinda like the hamburger model really

Reflect

Open education resources are one flavour of 'veges' in our burger metaphor. The significance here is that these resources are 'open' and can be used free of the constraints placed on other resources and learning content. Consider:

- How would you explain the concept of Open Education Resources to a colleague?

- How could you make use of OERs in your preparation of online teaching materials? What steps would you have to take in terms of storing and managing these?

- Could you see a way of implementing a Creative Commons policy in your context to cover the work of teachers and students? Wha practical steps could you take to implement that?

Creating your own resources

In this section we want to introduce you to some simply tools and applications that are free for you to use to create your own resources and media for use in your online learning episodes. Creating interesting and dynamic resources can be easier than you might imagine, particularly if you are the sort of teacher who already creates slideshows, videos or graphics for use in your classroom.

One of the most useful features in a number of online resource generating applications is being able to take advantage of the 'embed' code to include the resource you create directly into your online learning episode. (You'll note that we've included a few of these in this course). Several of the resource creation applications listed below have this feature, and you are encouraged to try them out.

Make your own media

There are dozens of applications available online that make it easy for you to create resources to use in your online learing environmnent. Here are just a few:

- Slideshare - upload your slideshows and other documents (incl. Powerpoint, Keynote, Open Office) and use the embed code to include these in your online environment. Slideshare has advanced features allowing you to embed Youtube clips in the slideshow, and the ability to record a sound track.

- Youtube - a popular site to upload video clips to then use the embed code to include in your online environment.

- Teachertube - similar to Youtube, but designed specificlly for educational content.

- Voicethread - a powerful and effective way of sequencing images and slides, and attaching text and audio comments. Very effective as an alernative to the traditional threaded forum - lots of opportunities to be explored with this one. Once compelted there is an embed code to allow this to be included in your online environment as a resource to review.

- Audacity® is free, open source software for recording and editing sounds. It is available for Mac OS X, Microsoft Windows, GNU/Linux, and other operating systems.

- Picnik - take your photos directly from Flickr, Facebook or Picassa and use Picnik's editing tools to edit you them and get creative with oodles of effects, fonts, shapes, and frames.

- Wordle is a fun way to generate “word clouds” from text that you provide. These can be used as graphics to add 'punch' to your online environment - you'll need a screen capture application to save the images and use them.

- Gliffy - Easily create professional-quality flowcharts, diagrams, floor plans, technical drawings, and more!. Enables 'save-as' feature for the images you create.

- TooDoo is an easy to use application to create your own cartoons that can then be embedded in your online environment.

- Recordr is a way you record yourself live just with a microphone and a web camera, and share it with your friends. By using our bookmarklet, you can also comment with video/audio to a web page you are viewing. There is also an embed code available for the videos you create.

- MindMeister - an online mind-mapping application that allows you to 'embed' your map directly into your online learning environment when you have completed it.

- MindModo - another online mind-mapping application that allows for 'embedding' of your maps - 30 day free trial available.

For more lists of applications that you can explore at your leisure check out these links:

- Make your own media a page on the copyright friendly wiki providing links to a range of media creation tools that are freely available.

- Image creators and clipart - a page on the copyright friendly wiki providing links to a range of applications for creating your own images, plus links to galleries of clipart.

- Concept mapping tools - another page on the copyright friendly wiki with links to a range of concept mapping tools. Concept maps are very useful for creating images to illustrate ideas and concepts in online learning content.

It can often be an advantage to 'make your own veges' in our burger metaphor, particularly when what you are after isn't available or is only available subject to formidable copyright restrictions.

The appications listed above are just a selection of what is available. You may know of others that you find valuable.

Images and icons

The use of icons provides a useful way of guiding learners around the content in an online learning experience. Icons should be simple and used consistently throughout the structure of the course - and the number used should be limited.

There are a number of icon sets available on the web - some are commercially available while others are available in the public domain through the creative commons license.

Crystal Clear Icons from the Crystal Clear icon set by Everaldo Coelho is one of the most well known of these. The icons are licensed under the GNU Lesser General Public License (LGPL).

These icons can be downloaded in a single package at Open Icon Library. You can then select the set you want to use and save them into a separate file for use with your online learning experience.

Images

Images can be used to good effect to help illustrate ideas and to provide a visual reinforcement of the content. When choosing images it is imprtant to ensure that you have the permission to use them, or you risk breaking copyright.

Some graphics can be created simply by using the draw tool in your word processor, or another graphic creation application such as a mind mapping tool like Inspiration or its web-based verision, Webspiration. Graphics created this way can be saved using a simple screen capture tool and inserted into your online content.

If you can't create the graphic you need, there are plenty of libraries available that use the creative commons license. Some are listed here:

- Image gallery on Wikimedia Commons - a growing collection of photographs and images that are free to use under the creative commons license. The license conditions of each individual media file can be found on their description page.

- Flickr is an online image repository, contributed to by subscribers, that can be searched by tag and category. Users can assign a copyright note to each photograph or image they upload. Check out the Creative Commons or the Creative Commons Free Pictures groups on the site - all the images in these collections have a creative commons license.

- Copyright Friendly - links to dozens of sites on this Wikispaces page containing Copyright-Friendly and Copyleft (Mostly! iImages and sound for use in media projects and web pages, blogs, wikis, etc. Though you may not need to ask permission to use them when publishing on the Web for educational purposes, you should cite or attribute these images to their creators unless otherwise notified!

- FreePhotoBank - a free stock photo site. Feel free to download pictures (up to 2048 pixels, Creative Commons licence) but don't forget to link back to FreePhotoBank.

- OpenClipArt - Unless noted, content on this site is waived of all copyright and related or neighboring rights under theCC0 PD Dedication.

Note: always check individual licensing notices before publishing on the Web or broadcasting!

Discuss

Images and icons are an important part of our 'vege' collection in our burger metaphor. They help to illustrate key concepts and contribue to the support aspect by aiding navigation around the site.

- What images are you going to need for your online learning episode? Can you find something useful using the links provided above?

- Do you plan to use a set of icons in your online learning experience to assist learners navigate the site? Can you compose a useful 'set' from the sites above?

Supporting online learning

Providing support for online learners is one the three key instructional design planks for online teaching. In this module you will be introduced to three key areas of development for providing support for learners. By working through the module you will:

- consider the ways in which you scaffold and support learners as they participate in the online learning.

- review ideas about feedback and assessment, and how these apply in an online environment.

- learn about the importance of developing an online community as a means of providing peer-support in an online course.

For those with less time to spend on this module we recommend you skin the questions posed in the 'reflection' section at the end of each of the topics to check your understanding of what is being covered. Of these we recommend you focus on the scaffold and support page, and refer back to the other areas when planning your online learning experience to help inform decisions there.

Supporting learning

In our face-to-face teaching settings we tend to provide support for learners in a range of ways, many of which we do instinctively or based on practices that are well established and we simply replicate. Consider the following for instance:

- arrangement of desks and chairs

- scheduling of lessons

- storage and access to resources

- library issuing systems

- circulating around the class to respond to student questions

- instructional charts displayed on the wall

- group processes explained in advance and used by students

These are simply a few examples - you're bound to be able to think of many more. In the online environment the support we provide needs to be considered as a part of the learning design process - not left to chance, relying on the synchronous sessions or when students raise concerns in the forums or email.

Here's a simple checklist of things that you might consider when thinking about supporting learners online:

- Have you assessed learner needs in some way so that you can be sure the learning experience will be suited to where they are at and where they need to move to? You can use a variety of strategies for this, including a range of diagnostic tools, pre-tests etc. One of the most helpful ways is to simply invite learners to share their expectations of the course at the beginning, and ensure you respond with suggestions about how they might go about making sure these are met.

- Have you created multiple pathways for engagement in the course so that learners with different approaches and styles can plot their own way through the experience?

- Is there a course map to help learners find where they are at any point in the experience, and support them in finding their way to where want to be without having to reference back to the facilitator all the time?

- Are the expectations of the course clearly stated, and are the assessment criteria shared with the learner at the beginning of the course? Where appropriate, is there opportunity for the learner to paticipate in establishing the assessment criteria?

- Is there a clear schedule of events and key dates available for the learners? Does this give adequate time for planning of key events in the course (i.e. synchornous events) and, if necessary, time for negotiation and change?

- Are there regular course announcements that appear on the course main page, and are these emailed out to learners to 'pull' them back to the course environment?

- Do you respond to the forums in a timely fashion, and when you do, do you provide suggestions for further action or prompts for deeper engagment? Do you encourage learners to respond to each other by providing feedback and suggestions?

- Have you provided your contact details so that learners have a way of communicating directly with you if they are stuck or encounter interruptions to their learning? Sometimes it can be useful to provide an 'open forum' where learners can share ideas, thoughts and questions about things that aren't directly related to the course content.

- Have you checked that all links to resources are current and working, and that the materials you use are accessible by all learners (i.e. at no cost, will work on all browsers and types of computer etc.)

- If you have planned for synchronous participation, can you be sure it is scheduled at a time where all learners are able to make it, and that all learners will have access to the necessary equipment/applications? Are you sure tht the synchronous participation must be compulsory, or can it be more like a tutorial that 'adds value' for those who can make it?

- Is the online learning environment easy to navigate? is the navigation consistent throughout, and does it reflect what is shown on the course map? Are there hyperlinks inlcuded within the modules to re-direct to other parts of the site?

Scaffolding strategies

Many of the things we do quite intuitively in face-to-face settings provide learners with the assistance they need to promote learning when concepts and skills are first being introduced. This sort of support is commonly referred to as scaffolding - instructional strategies that enable the learner to take steps that are appropriate for them.

Many different facilitative tools and strategies can be used to scaffold student learning. Among them are:

- Breaking tasks into smaller more, manageable parts

- Prompting for reflection and feedback

- Providing templates or graphic organisers to assist with thought development

- Promoting teamwork and dialogue among peers; concrete prompts, questioning

- Coaching; cue cards or modeling

- The activation of background knowledge

- Giving tips, strategies, cues and procedures

Crucial to successful scaffolding is an understanding of the student’s prior knowledge and abilities. The teacher must ascertain what the student already knows so that it can be “hooked”, or connected to the new knowledge and made relevant to the learner’s life, thus increasing the motivation to learn.

Teachers have to be mindful of keeping the learner in pursuit of the task while minimizing the learner’s stress level. Skills or tasks too far out of reach can lead a student to his frustration level, and tasks that are too simple can cause much the same effect.

FURTHER READING

Here are some links to material that might help you with your understanding of what is meant by scaffolding learning:

- Scaffolding learning - from MyRead, looking specifically at strategies for teaching reading in the middle years, but the principles apply more generally.

- Scaffolding for success - from Jamie McKenzie. Provides a useful overview of what is meant by scaffolding learning and its characteristics.

- Zone of proximal development and scaffolding - from the Victoria Department of Education - useful summary of the theoretical background to the idea of scaffolding.

Discuss

Support and scaffolding strategies are another part of the 'bun' in our hamburger metaphor. Each makes an important contribution to the support that online learners receive as they work thorugh the course activities and content.

- How are some of the suggestions for supporting learners embedded in this course? How helpful have they been to you? How difficult could participation have been if they weren't there?

- What other examples can you think of from your classroom experience, and how might these be translated into the online environment?

- What forms of support and learner scaffolding are you planning on incorporating in your online learning episode? How will you monitor its success (or otherwise).

Feedback and assessment

In recent years there has been plenty of research evidence illustrating the positive impact that teacher feedback can have on student learning. This is particularly true in online learning, where the immediacy of the face-to-face environment is gone, and with it the non-verbal forms of feedback that can often play an important role.

Lack of feedback in the online environment can lead to dis-engagement, or sometimes worse, hours spent in study and the completion of assignment work that 'misses the mark' somehow.

Online feedback can be provided in a number of ways, including:

- through the discussion forums

- privately via email or a personal phone call

- in notes attached to assignments or tasks submitted in drop-boxes

- during synchronous sessions (video conference, webinar etc.)

The purpose of feedback can include:

- identification of problems and areas to work on to improve

- providing specific actions or direction for development

- clarifying areas of concern or confusion

- enabling students to build more accurate self-assessment skills

Feedback also needs to be of good quality and purposeful. Here's a simple list of do's and don'ts of effective feedback to remember:

| Do |

|

| Dont |

|

READINGS

Further suggestions can be found in the following links:

- Tips for grading and giving feedback - a list of useful tips from Edutopia that can be applied in the online context.

- Giving students more effective feedback - from Faculty Focus, these tips are based on examples involving written assignments, but could easily be applied elsewhere

- Giving student Feedback: A Teacher's Guide - an excellent resource from George Brown College with an extensive list of tips and tools (and links) that can easily be applied in the online environment.

Assessment

There are whole courses and books written on this topic, much to cover in this short part of our course. Here we will assume that, as teachers, you will have a good understanding of what good assessment practices are and instead summarise just a few of the key things that are important to consider when building assessment into your online learning experiences.

- Make assessment requirements explicit from the outset - this is one of the key ways of providing support for learners in an online environment, where they will be having to 'map out' for themselves how they will engage with the learning tasks. There's an addage in the instructional design world that you should 'start with the end in mind'. In other words (using the car journey metaphor), have a clear idea of what the destination is and share the criteria by which learners will know if/when they've reached it.

A useful way of presenting this to learners is to create and share a rubric for the assessment process. A rubric consists of three key parts:

- the criteria against which the assessment will be made

- the stages of progression that show growth and development

- the indicators describing what is observable at each stage in the progression

As learners become more familiar with the use of rubrics to assess their work they can become involved in the development of them also, negotiating the creation of the indicators to match the criteria, and also in making choices about the evidence they will need to gather as proof that they have achieved at the various levels.

Some examples: Science rubric, oral presentation rubric, research project rubric

- Assess what matters - a trap that many new to online teaching fall into is to make it mandatory to submit almost every task for assessment, presumably because they feel obliged to 'check up' on learners to compensate for the lack of eye contact and classroom presence they might rely on in face to face situations. Focus on the development of a key activity or challenge that incorporates all of the aspects of what is to be learned, and create the assessment to match that. This approach has been modelled in the course you are completing now.

- Include diagnostic, formative and summative assessment approaches. remember that there are many forms of assessment. The advice above relates to the summative assessment approach, where the focus is on demonstrating and providing evidence of achievement in the areas defined by the course objectives and/or lerning intentions. establishing a range of diagnostic and formative asessment approaches is also important. This is the purpose of the various tasks, activities and reflection points that are included. These provide an opportunity to demonstrate the development understandings that are occurring along the way, and it is important that you include appropriate feedback mechanisms in the course to ensure learners are informed of when they are on the right track - or not (see section on feedback above).

- Cater for personal an peer assessment approaches. assessment need not be something that is the sole perogative of the online teacher/facilitator. With the criteria for assessment being shared among the learning community, it becomes something that the group can participate in providing feedback and critique on. This is the purpose of the various forums as places where learners can share ideas and thoughts, and where other learners can respond in ways that add value and provide direction. Online survey tools are particularly useful for self-assessment, providing a substitute for the sort of questions that a teacher may ask as they roam a classroom.

READINGS

For more information about approaches to assessment, particularly the development of rubrics, choose the following links:

Defining a rubric: http://edservices.aea7.k12.ia.us/framework/rubrics/defining.html

Rubric Construction Set: http://landmark-project.com/classweb/tools/rubric_builder.php3

Rubrics and rubric makers:http://www.teach-nology.com/web_tools/rubrics/

Kathy Schrock’s rubric examples: http://school.discovery.com/schrockguide/assess.html

Sample rubrics for different subjecs: http://www.rubrics4teachers.com

Discuss

Feedback and assessment strategies are another part of the 'bun' in our hamburger metaphor. Each makes an important contribution to the support that online learners receive as they work thorugh the course activities and content.

- What provision for feedback have you planned to include in your online learning experience? Have you planned this in such a way as to avoid it becoming a burden for you as the online teacher? How will you know that learners are receiving the feedback they require?

- What will be the focus of assessment in the online learning experience you are planning? is it the 'stuff that matters'? Or are you over-assessing the 'small stuff'? If you need to be assured that learners are making progress towards the major task how else could you do this?

- How are you planning to share the learning objectives/intentions for your online learning experience with students? How do you plan to share the assessment criteria also? Will you make provision for self and peer assessment as a part of your approach?

Discuss

Feedback and assessment strategies are another part of the 'bun' in our hamburger metaphor. Each makes an important contribution to the support that online learners receive as they work thorugh the course activities and content.

What provision for feedback have you planned to include in your online learning experience? Have you planned this in such a way as to avoid it becoming a burden for you as the online teacher? How will you know that learners are receiving the feedback they require?

What will be the focus of assessment in the online learning experience you are planning? is it the 'stuff that matters'? Or are you over-assessing the 'small stuff'? If you need to be assured that learners are making progress towards the major task how else could you do this?

How are you planning to share the learning objectives/intentions for your online learning experience with students? How do you plan to share the assessment criteria also? Will you make provision for self and peer assessment as a part of your approach?

Share your questions, thoughts and ideas in the supporting online learning forum.

Building a community

Developing a sense of 'community' among the cohort of online learners is perhaps one of the most significant pieces of 'vege' in our burger metaphor. Online learning is often thought of as a rather isolating experience, a 'solo effort' where the sorts of inter-personal interactions we take for granted in a face-to-face context can't or don't occur.

While this can be the case, as online teachers we can take deliberate steps in our instructional design approach to ensure that learners have every opportunity to connect with other learners, and for the sense of 'community' to grow an develop.

Not all courses lend themselves to collaborative effort in assignments or tasks, but all can build community through communication and sharing, peer feedback and critique etc. The sorts of interactions tha can help promote this sense of community can occur at three levels: communication, cooperation, and collaboration. These form the basis of what we call the five Cs of online community development:

- Cohort: The cohort is the cohort of learners participating in the course as a group. They may have an initial connection, such as a common employer, but it does not necessarily constitute a strong bond.

- Communication: Communication is defined here as the basic level of discussion in an online format. Learners must participate in discussion to have any sort of presence in the class whatsoever. Communication can be focused around readings, presentations, and any other ideas based on course content or course administration. Communication can occur asynchronously in the online forums or via e-mail, or synchronously via webinar or audio/video conference.

- Cooperation: Cooperation entails students working in groups or otherwise dividing up tasks. A machine metaphor can illustrate cooperation in the classroom: different parts of the machine perform different functions and goals, but work together towards a similar end. For example, learners may divide up a project, but are eventually assigned individual grades for their work. Examples of cooperative tasks include: dividing up sections of a report to write and doing peer review of each other’s work.

- Collaboration: Collaboration is the most integrated form of group work, and is therefore potentially the most difficult and the most rewarding. In the case of collaboration, the group members work toward a common goal, one that carries a mutual investment. For example, learners may each work on every part of a report, consulting each other and re-reading each other’s edits. They are invested in every part of the project because they will share a common assessment. Examples of collaborative tasks might include group writing, creating a movie, and developing a shared science project.

- Community: A virtual learning community is one of the ultimate goals of the core courses. When a cohort of learners participating in the same online course develop to become a learning community they become capable of developing ideas and understandings that transend what exists in the framework of the course itself. In addition, the community assumes much of the responsibility for supporting other members in their learning, so the responsibility doesn't rest entirely with the course facilitator.

Online learning communities don't just 'happen', nor can you 'make' one develop. But you can plan for the right circumstances to exist in your course design so that the chances of a learning community developing are greatly increased.

Further reading

For more information about online learning communities you might be interested in the following readings. They are rather academic, but provide an excellent background if you're interested in developing your own insights in this area:

- Key Elements of Building Online Community - an academic paper that explores the perceptions and challenges of building community in online classes.

- Building an online learning community - links to a slideshow by Jane Hart, a social media specialist from the UK, who presents a range of tools and environments that can be used for building learning communities online.

- Developing an online learning community - academic paper presented at the 2009 ascilite conference in Auckland, NZ. Reports on a research project into student experiences in an online course - very useful if you're considering researching this sort of thing in your own context.

- Online Learning communities: investigating a design framework - (Brook and Oliver) Academic paper presented at the 2003 ascilite conference, investigates the development of online communities and has a useful table showing elements and attributes that create a sense of community.

Discuss

Building a vibrant online learning community is possibly the most important support strategy you can aim for in your online teaching, Not only does it reduce the amount of direct responsibility placed on you as the teacher, the overall impact is one where the combined efforts of the group will be more than the sum of the indivudal parts (synergy).

Think about the online learning experience you're preparing in this course.

- How will you design the approach to best enable a learning community to develop? Are you planning any cooperative or collaborative activity?

- How will you monitor (and assess) the development of this community?

- When would you consider it appropriate to intervene in the way the community develops?

Pedagogy and technology

In this module you'll explore the relationship between the approches to teaching that you choose, and the online technologies available to you. By working through this module you will:

- Review understandings about learning theories and how these inform your work as a teacher

- Consider the various online pedagogies you may engage in

- Consider the range of online technologies available to you to use

- Complete a matrix activity to demonstrate your understanding of the relationships you see between pedagogical approaches and technology use.

For those with less time to spend on this module you may like to go straight to the matrix activity and attempt to complete it, using the other topics in the module to refer to as you need to.

An introduction to learning theories

A theory is an organised set of statements that allows us to explain, predict, or control events.

- In education there are a range of theories which have been developed to assist us in understanding the craft we are involved in, and to explain some of the structures we operate within. Many of these apply universally, regardless of whether we are talking about distance education or conventional, classroom-based education.

- Just as our approaches to teaching in a face to face setting are informed by appropriate learning theories, these same theories should inform what we do online. This section is intended to assist you in reviewing your knowledge of what we understand about learning and the theories that have been developed to guide what we do as teachers.

Watch this slideshow which provides a quick overview of some of the main ideas, while the list of links that follow provide more detailed explanations of these and other theories.

Links for further reading

- Instructional Development Timeline - an excellent table providing an overview of the relationship between learning theories and theorists, and the development of instructional processes.

- Explorations in Learning and Instruction - the theory into practice database containing brief summaries of 50 major theories of learning and instruction.

- Instructional Design and Learning Theory - an excellent summary introduction to the whole area of instructional design and learning theory - can be printed out in Word or PDF

TASK: a personal philosopy of teaching

This task has two purposes:

to help you 'unpack' the things you believe about effective teaching and learning, and to help you articulate these thoughts with other course participants

to provide a 'benchmark' in the course that you will be asked to refer to and reflect on at different points as the course progresses.

Everyone has their own view of what contributes to effective teaching and learning, and this will be informed and influenced by our understandings of learning theory, of the contexts and disciplines within which we teach and our personalities.

- Summarise your personal approach to teachng in the form a brief personal philosophy of teaching and learning (approx 200 words) - making reference to the relevant learning theory(ies) that inform your approach.

- Share a story from your own experience that is an example of a 'successful learning experience' (could be f2f or online) to illustrate your personal philosophy in action.

Online pedagogy

What do we mean by online pedagogies? Is there, in fact, such a thing - and how do they vary from other forms of teaching and learning (ie face-to-face).

In this course the term pedagogy is understood to mean the science, art and craft of teaching and learning. In other words, the decisions that we, as teachers, make in our planning and teaching of a lesson will involve aspects of disciplined (scientific) thinking, creative ideas and episodes, and will be informed by educational theory as well as our experience and practice (our craft).

The thinking you are asked to summarise in the task is about pedagogy - the practices the things that you do as a teacher in the belief that they will result in learning occurring. The theories and theorists referred to in the readings for this module have all informed, so some extent or another, the pedagogies we embrace in face-to-face classrooms, and must now consider in the online environment.

As we move into an online teaching and learning environment, many of the practices that have been employed in a face to face context are coming under the spot light. Teachers have begun to think more critically about their work, and question whether conventional practices can be applied to an online environment.

Pedagogical approaches

Below is a list of approaches to teaching and learning reflecting a variety of pedagogical thinking. This list is not definitive, but intended to prepare you for the task that follows. Take some time to read this list and..

use a search engine to find further information on any of the above that you may not be familiar with or want to know more about, and

add to the list any other approaches that are familiar to you, particularly those you use often in your current teaching.

- Co-operative Learning

- Learning Centres / Stations approach

- Differentiated Learning e.g. Multiple Intelligences

- Experiential Learning / Authentic Learning / Outdoor Learning

- Activity-based Learning e.g. hands-on with manipulatives

- Debates, Role-plays and simulations

- Readers’ Theatre

- Shared Book Approach

- Quizzes

- Games based learning

- Problem-based Learning (PBL)

- Adventure-based Learning (ABL)

- Mindmapping

- Student-on-Stage e.g. ‘Student as Teacher’ and Show-and-Tell

- Cooperative learning

- Inquiry-based Learning

- Jigsaw approach

- Buzz Group

- Individual conferencing

- Personal research

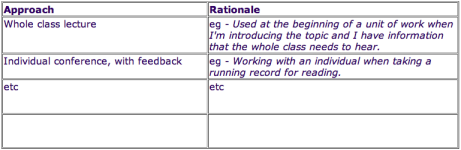

TASK - pedagogical approaches

This activity is a designed to be completed before undertaking the matrix activity.

Take a few minutes to make a list of all the teaching and learning approaches that you would typically use in the course of a week's teaching. Use the list above to help you. Your list may include a wide range of approaches, representing points at all extremes of the continuums listed earlier. For each approach you think of, write a brief statement which describes why you use that approach, including reference to the context. The table below gives you an idea of what we're suggesting:

You may find it helpful to download this template to complete this activity.

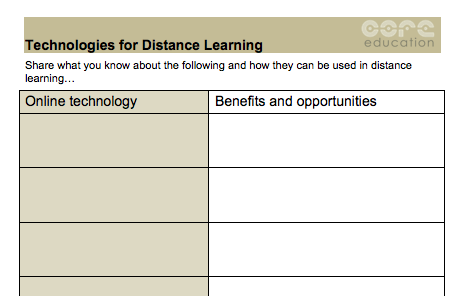

Technologies for online learning

In the online environment there are is an ever increasing range of technologies that may be employed. From the traditional Learning Management Systems (such as the one we're using for this course) through to the range of Web2.0 technologies, there is now a wide range of choice. These may be thought of in the following ways:

- Applications for organising, managing and sharing course content - including traditional LMSs, wikis and web sites.

- Applications for promoting interaction and participation - including synchronous and asynchronous technologies.

- Applications for creating and authoring content - including a range of installed and web-based applications.

To be an effective teacher in the online environment you will need to develop some familiarity with the range of technologies available in order to be able to make informed decisions about their use.

Some examples

The list below provides you with some examples of the sorts of technologies and applications you might choose to use when teaching in an online environment.

Applications for organising, managing and sharing course content

- Learning Management Systems - e.g. Moodle, Blackboard, Ultranet

- Wikis - e.g. WetPaint, Wikispaces

- Blogs - Blogger, Wordpress

- Social network systems - Facebook, ELGG,

Applications for promoting interaction and participation

- Threaded forums (included in most LMSs),

- Drop boxes

- Audio conferencing

- Video conferencing (Skype,

- Webinars (Adoble Connect, Elluminate)

- txting, pxting

Applications for creating and authoring content

- Word processing - Word, Google Docs, Open office

- Illustrations - Google sketchup,

- Video - Teachertube, Youtube,

- Slideshows - slideshare, Google show

Are there any of the ICTs in the list above are you not familiar with? If so, do a "google" search to find out a little more about them, or ask a question on the discussion board for clarification.

You may think of others you could add to this list - feel free to share them and a little of what you know about them from your personal experience in the module forum.

Identifying technologies to use

Use the format below to make your own list of technologies you feel comfortable with using, or that you'd like to become more familiar with. On the left hand side list the specific technology or application, and in the right hand column describe the specific ways in which you would use it as an online learning tool.

You may prefer to download this template to assist you with the task.

Matrix activity

Preparing the matrix